SOUTH AFRICAN EDEN

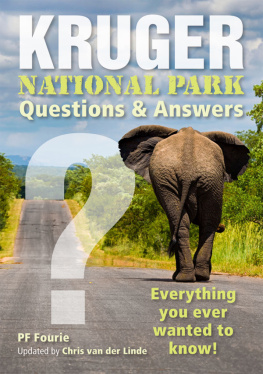

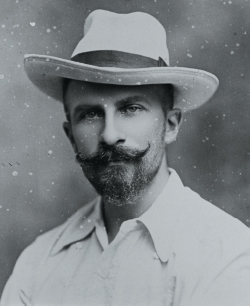

James Stevenson-Hamilton (1867-1957) was born on the family estate near Glasgow and educated at Rugby and Sandhurst. At a loose end after participating in the South African War as an officer in the Inniskilling Dragoons, in June 1902 he was appointed as warden of the Sabi Game Reserve in the Lowveld, along the Eastern Transvaal border with Mozambique. This was later to emerge, thanks to two decades of epic determination on his part, as the world famous Kruger National Park. A controversial and pioneer wildlife conservationist, he was also a prolific propagandist and fine storyteller. His cause was turning his corner of Africa from a depleted hunters paradise into an unsullied refuge where the indigenous wildlife might be preserved in its natural order as an inheritance for future generations. He is noted as one of Britain and South Africas first ecologists.

His frequent and stylish articles on the topic of environment management were published in journals such as The Field, Blackwoods, The Times and The Outspan. These were expanded into books, including Animal Life in Africa (1912), The Lowveld: Its Wild Life and Its People (1929) and Wild Life in South Africa (1947). But it is his passionate memoir South African Eden of 1937 which has achieved classic status. Subtitled From Sabi Game Reserve to Kruger National Park, it was issued in a second edition in 1952, then included in 1956 in George Cansdales Wild Life Series for Panther. This latter text, with its updating and epilogue, is followed here.

In 1930 he married the artist Hilda Cholmondeley, who became well known as an illustrator, particularly of her husbands work. Three children were born of the union, two of them brought up at their Sabi Bridge encampment, or at Skukuza, as it is named after him today. In 2001 the eminent historian, Jane Carruthers of the University of South Africa, published her biography, Wildlife and Warfare: The Life of James Stevenson-Hamilton, and here she has acted as consulting editor.

Strat Caldecott in The South African Nation (30 July 1927):

In the Sabie the Warden, Col. Hamilton, has established an understanding between his staff and his lions so perfect that the latter never attack humans at all, and cattle very rarely, and then with a cunning that proclaims a guilty conscience. Also, they seldom do it more than once.

Harry Wolhuter in Memories of a Game Ranger (1948):

One could have had no better chief than J Stevenson-Hamilton, and no superior officer was more loyal, kind and considerate to his subordinates. To a very great extent the world we lived in was a secluded one of our own, so we had to depend much upon one another.

Alan Cattrick in Spoor of Blood (1959):

I never see a Western film in which the tenderfoot walks somewhat timorously into the saloon where the cowhands are gathered without having in my minds eye a picture of James Stevenson-Hamiltons first visit to the Eastern Transvaal.

A P Cartwright in Better than They Knew (1972):

He had the inspiration for which South Africa owes him a debt of gratitude that it can never repay. In 1926 he lifted the reserve above local jealousies, and all demands for its abolition, by seeking to have it made a national park the property of not one province, but of all the people of South Africa.

Mary Morison Webster in The Sunday Times (14 April 1974):

When Colonel Stevenson-Hamilton retired in 1946, he left South Africans a rich heritage in the Kruger National Park, which he had been largely instrumental in establishing and developing. This book, first published in 1937, is his own account of what became at once an adventure and a challenge.

James Clarke in The Star (5 June 1974):

South African Eden is worth reading again. In fact, if you know the Park, I can vouch that youll not put the book down. It is, of course, splendidly written.

Brian Keet in Weekend Post (2 October 1993):

The writing is elegant and colourful and the anecdotes conjure up exciting, rewarding and often humorous times in the formative days of the worlds most famous wildlife park.

The author in 1899 and after retirement in 1946

Preface

In the following pages I have endeavoured to set forth the story of the Kruger National Park or, as it was known for more than twenty-five years, the Sabi Game Reserve, from the date I was placed in charge of it on 1 July 1902, until my retirement on 30 April 1946.

It must therefore be understood that what I have written refers only to persons, events, and system of administration, embraced within that period. Of subsequent history I know little, and that at second hand: consequently I do not touch upon it.

My desire is merely to record how the great wildlife sanctuary, as the public know it today, came into being; how it for long struggled for existence against heavy odds, and how at last it came successfully to maturity.

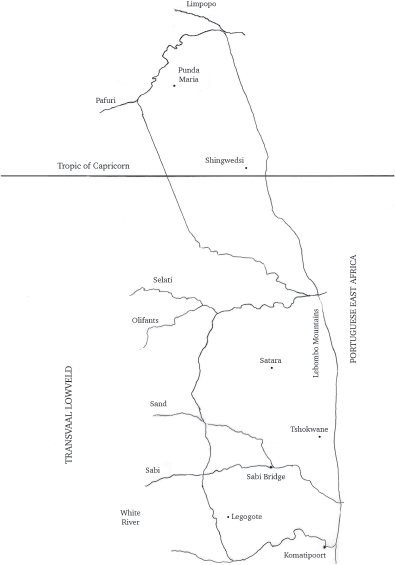

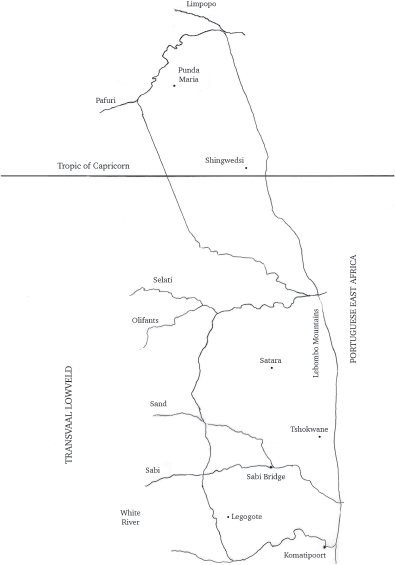

Sabi and Shingwedsi Game Reserve

1

First Impressions

It is the afternoon of 25 July 1902. On the edge of the last escarpment of the Drakensberg, overlooking the huddled welter of bush-clad ravines and rocky terraces which compose the foothills, my little caravan has come to a halt that I may for a while absorb the wonderful panorama of mountain and forest which has just disclosed itself.

The sun, low in the west, is gilding the bare pinnacle of Legogote and is lending fleeting shades of delicate pink to the three peaks of Pretoriuskop border beacons of the land of mystery beyond. Eastward, far as the eye can see, stretches a rolling expanse of tree-tops; in the foreground a medley of green, yellow and russet brown, but with increasing distance merging into a carpet of blue-grey, which, as it recedes, assumes an ever fainter hue, until at last it blends with the dim haze of the horizon. Far away down the slope of the mountain lies the lonely homestead of which I have been told: Sandersons farm, in its complete solitude and abandonment, a component part of the surrounding wilderness.

Wildlife is just awakening from its afternoon siesta. Francolins are calling all around, and from a nearby donga comes the sudden clatter of guineafowl. Bush babblers are chattering among the trees, their cheerful din serving to render yet less definable the vague sounds which here and there are beginning to rise from the distant forest. It is the voice of Africa, and with it comes to me a sense of boundless peace and contentment.

But it is getting late, so I unwillingly come back to earth, mount and give the order to proceed. The tired oxen seem to sense this to be the last stage of their long days trek, and the waggon jolts rapidly down the rough road, corrugated with deep ruts and dotted with large stones. Finally, amid the appropriate shouting and creaking of brakes, we draw up before it is yet dark in front of Sandersons farmhouse. Except for a few guineafowl (remnants of a tame flock) the place is quite deserted, and the house thoroughly cleared of everything movable; but its walls and roof remaining intact, it provides a welcome shelter of which we gladly avail ourselves.