For my African family, Lindsay, Reza, Nina, Miari, Max and David And for Olivia, my beautiful Singaporean granddaughter

Published by Struik Nature

(an imprint of Random House Struik (Pty) Ltd)

Reg. No. 1966/003153/07

First Floor, Wembley Square, Solan Road, Gardens, Cape Town, 8001

PO Box 1144, Cape Town, 8000 South Africa

Visit www.randomstruik.co.za and subscribe to our newsletter for monthly updates and news

First published 2012

This eBook edition 2012

Copyright in text, 2012: Mitch Reardon

Copyright in photographs, 2012: Mitch Reardon, except where otherwise indicated

Copyright in published edition, 2012: Random House Struik (Pty) Ltd

Copyright map, 2012: Random House Struik (Pty) Ltd (base map by Chris and Mathilde Stuart)

Publisher: Pippa Parker

Managing Editor: Helen de Villiers

Editor: Lesley Hay-Whitton

Project Manager: Colette Alves

Design director: Janice Evans

Designer: Louise Topping

Cartographer: Martin Endemann

Proofreader and indexer: Emsie du Plessis

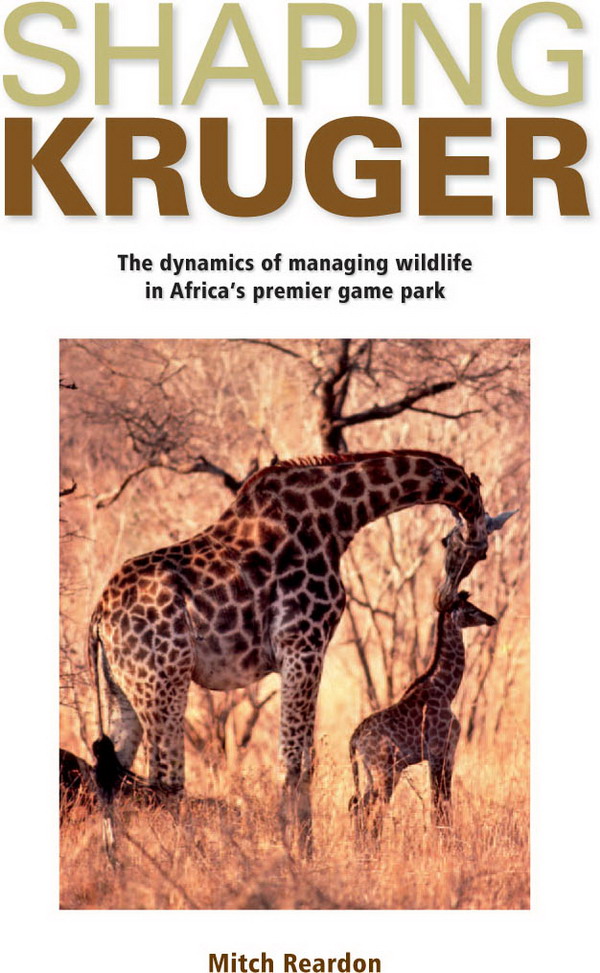

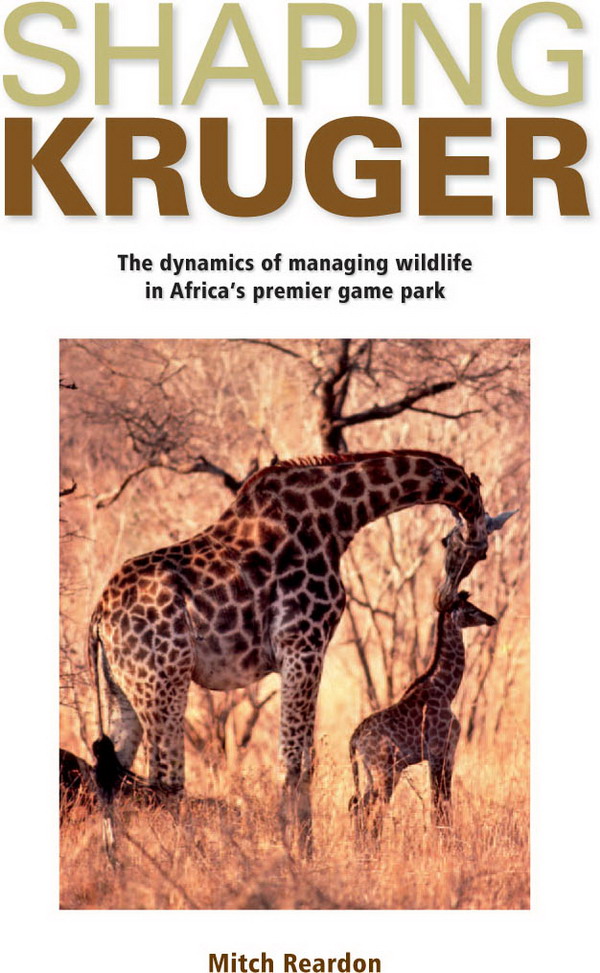

Picture credits (front cover): Gerald Hinde; insets: Walter Jubber

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner(s).

ISBN 978 1 43170 245 9 (Print)

ISBN 978 1 77584 017 6 (ePub)

ISBN 978 1 77584 016 9 (Web PDF)

To download a comprehensive bibliography, go to www.randomstruik.co.za/krugerbiblio

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to Professor Norman Owen-Smith, a friend and A-rated scientist in the School of Animal, Plant and Environmental Sciences at the University of the Witwatersrand, who taught me a great deal about the ecology and behaviour of the Krugers large mammals while patiently fact-checking the first draft of the manuscript. I would also very much like to thank Dr Harriet Davies-Mostert and Jessica Watermeyer who made many helpful comments regarding the Cheetah and Wild Dog chapters. They are, of course, in no way responsible for any errors that may remain. I am grateful to Yolan Friedmann, Grant Beverley and Andr Botha from the Endangered Wildlife Trust for help and instruction during my field research, and to Kelly Marnewick, for fact-checking the Cheetah chapter and supplying much needed fieldwork photographs. And, finally, special thanks to my publisher, Pippa Parker, and my editor, Lesley Hay-Whitton, for providing a happy combination of good fellowship and professionalism. And to the editorial and design team at Random House Struik: Colette Alves, Louise Topping and Helen de Villiers, for the stream of creative ideas and plain hard work.

Contents

Looking west from the crest of Nkumbe Escarpment.

O ne crisp winter morning, I stood on the crest of Nkumbe Escarpment in southeast-central Kruger National Park, and gazed westward across weathered, straw-yellow grassy plains furrowed by a drainage lines winding green course. There was barely a sound or sight to remind me of the immediate century; it was like peering into the past. I could see for miles, but not far enough to spot the nearest building or road. Except for where I stood, the few traces of humans were poignantly fleeting. It was an image of old Africa distilled.

Because of the grip wild country has on the imagination, we feel drawn to this rigorous landscape and its primordial paradox, its blend of claw and thorn and subtle beauty. You can almost envisage that era when Earthly patterns and relationships existed solely between the land, the weather and the animals, when nature worked with all its parts. But that impression of a missing human link could not be further from the truth. As the stories you are about to read make explicit, people and their works, good and ill, are very much at the forefront of the Kruger Park saga.

Theres another contradiction at play in these rugged, primeval expanses. With its potent allure, its not surprising that to the untrained eye this mighty savanna appears ancient and enduring. However, appearances can be misleading. Savannas are Africas newest environment. They arose around 25 million years ago when a dry phase swept across the entire continent, shrinking rainforests and ushering in an energy-rich, dynamic mix of woodlands, thickets and grassy plains. Nourished by seasonal rains and with year-round solar energy pumping through the food chain, this intensely physical landscape became a place of inordinate biological riches. Africas savannas still support the largest herds of herbivores on the planet, side by side with a mix of herbivore-eating carnivores. This profusion, this density of life, contributes to a natural unruliness. Studies have shown that savannas are far from constant; instead they are forever changing, but these fluctuations are a part of ecosystem functioning. At one extreme there are long-term oscillations, for example in climate and fauna and flora. We see only small parts of these in our lifetime. There are also short-term changes drought and deluge, fire, nutrient flow and the impact of browsing and grazing which manifest themselves in fits and starts. Intact ecosystems are generally resilient, with a capacity to absorb stresses and disturbances. How these biological systems operated before the influence of post-industrial humans is near impossible to guess, but what we do know is that there is no original condition to which we can hope to return, just as attempting to maintain the existing state is an ecological oxymoron; its also unrealistic for a dynamic ecosystem such as the Krugers. Change is inevitable; indeed, it is natural.

Grooming sessions help bond baboon society while freeing individuals of parasites.

The African savanna was also the place where some seven million years ago the evolutionary lines of apes and proto-humans diverged, with the descendants of the latter eventually gaining the upper hand, with all that meant to the other animals as soon as he got his hands on them. In the beginning, however, African animals co-evolved with members of our lineage. Africa still harbours many of the megafauna that roamed much of the Earth in the last geologic period, but which have largely been exterminated elsewhere; this is largely due to the fact that for millions of years a prehistoric arms race ensued as animals honed their attack and avoidance strategies in lockstep with our early ancestors improving hunting prowess. The nave big beasts in the Americas and Australia, by contrast, first encountered humans just tens of thousands of years ago, by which time we were already fully modern, highly intelligent, organised and wielding lethal weapons. Entire species were hunted to extinction before they had time to beware of these new technological predators. Now we have arrived at the point where biologists calculate that

Next page