Chapter 1: Aggression and the Constructional Aggression Treatment

R iley originally belonged to next-door neighbors of the people I knew as his family. He was about a year old when his first family moved away and left him behind, all alone, in the backyard. He was thought to be a Doberman mix, but I kind of wondered if he might be an Australian Kelpie. It doesnt really matter. He was Riley. His kind neighbors realized he had been abandoned and took him in. He was a good dog with them. He was gentle with their adolescent son and quite agreeable with his new family. They quickly fell in love with him.

Within a week, however, he lunged and growled at someone while on a walk with his new mom. They also soon realized that he wasnt at all nice to people who entered their home. They took to crating him when they expected company. One time, a friend came early for a gathering at their home while Riley was loose in the house. She knocked on the door, and, without hearing a response, she entered and carried a casserole into the kitchen. These were, after all, friends who were expecting her arrival. Riley promptly and loudly pinned this terrified woman in the kitchen. She was a cat person and not confident around dogs in general, so the whole event had an extra layer of scariness. The family was able to pull Riley away, and he did not hurt the guest, but it was a concerning situation and not the only time Riley did that sort of thing.

Riley was eleven years old when I met him. Thats pretty old for a pretty big dog, but he was still agile and strong, and he lived for several more years. Like most dog families, this family loved their dog, and they were willing to make a lot of concessions for him. In addition to crating him when guests came over, they had only one option when they needed to board Riley: their vets office. Riley didnt like the vet, but he did like one of the techs there, so they were able to board him when she was available. When I met with the family, they told me that if that particular tech wasnt available, the family would take separate vacations so that someone could stay at home with Riley. This was useful information. It told me that he actually had been successful in making friends outside his immediate family. He also liked the grandmother, who visited once or twice year. But they were the only ones.

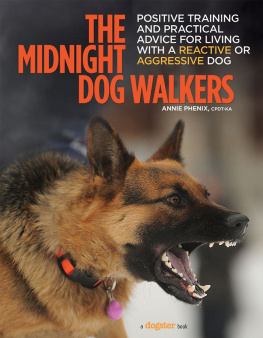

Lunging on the leash can be part of a dogs aggressive behavior.

The goal for training Riley was to help him make more friends. His owner told me, We just want him to be able to have friends. He doesnt have any friends but us. Maybe that wasnt important to Riley, but it was important to his family, and families matter, too. Families matter a lot.

Its hard to be the owner of a dog who doesnt like other people or animals, but its even harder when the dog exhibits aggressive displays and actions toward them. It makes for a frustrating and challenging life for the owners and has a significant impact on the whole familys quality of lifehuman and canine members alike. A lot of Rileys end up in shelters, and many are eventually euthanized because of their aggression when families just cant make it work. After working with a lot of these dogs, I understand that decision. It breaks my heart, but I usually support it. I feel deeply for those families.

I was pretty nave when it came to working with aggressive dogs at the time I began working on CAT. I was used to parrots and cats. But it didnt really matter. I didnt work with dogs, per se. I was working with their behavior. It sounds like an unnecessary distinction, Im sure, but behavior works in certain ways across all species, and it is those principles of behavior that we were studying in the research. In this book, you are going to learn how to study your dogs behavior.

Whether with your phone or a video camera, be ready to record your dogs training.

We didnt have a lab full of aggressive dogs to study at the University of North Texas, but families looking for help with their aggressive dogs were easy to find. Dr. Rosales often guides his students through working with animals in their homes, and that is what happened with me. Most of the dogs I worked with lived with families. A few lived in animal shelters. The way the research went was that I would go to pet owners homes or meet them in spaces where aggression was known to occur, and I worked with the dogs in their real worlds. In every case, I either set up a video camera on a tripod or had someone videotape what we did. I recorded the work I did with every dog. This was in the early 2000s before everyone had good cameras inside their easily portable smartphones. You probably wont have to buy a new piece of equipment to record your work, but make sure your phone is charged.

After each session, I took the videos back to Dr. Rosaless office to view them and discuss what went wrong and what went right, what else I might try, what to leave out, and what to add to what I was doing. We met every Wednesday at 2:00 p.m. (I called these my come to Jess meetings). Obsessive video recording and watching every video with your professor is a very effective way to get over your fear of seeing yourself on tape. The videotapes were extremely useful, so the embarrassment I sometimes felt was worth it.

To my great fortune, very little went wrong in terms of safety during my work on the procedure. I was bitten once by a large mixed-breed dog named Max, and ten years later I was bitten by a German Shepherd Dog named Gunther. I regret both of these events deeply, and not just because of the injuries I sustainedvery minor with Max, thanks to my heavy sweatshirt, and worse but not life-threatening with Gunther; I will always have a scar to remind me.

I confess that the bite from Max was totally my fault. I wasnt paying enough attention to the husband, who was handling the dog, or to the dog himself. I was explaining something to the wife, who was in front of me, and I happened to glance down at the dog to my left. Max was much closer to me than he had been a moment before. He was staring hard at me from close range. The husband was holding the leash loosely. I made the briefest of eye contact with Max before he launched himself upward at me. I raised my arm to block the dogs lunge toward my face. My favorite sweatshirt got a bite taken out of it, and I got a bruised wrist but no broken skin. It could have been much worse.

If you want to work with your aggressive dog, you have to pay attention. Distraction is not acceptable, and I was distracted. The incident you suffer might not be to your wrist. What if I had not looked down just then? He would have gone for my neck or face. You can tell where a dog is going to bite by where he is staring, and he wanted my head.

No bite, severe or not, is acceptable.

With Gunther, it is not as clear to me what happened. I still ponder it, but the best advice I can give myself is that I should have worked slower. When in doubt, take a break, watch your videos, and think it through. On that particular day, I wanted to work up to at least the point we had gotten to in our previous session, but Gunther wasnt up for it.

Next page