Contents

Shambhala Publications, Inc.

4720 Walnut Street

Boulder, Colorado 80301

www.shambhala.com

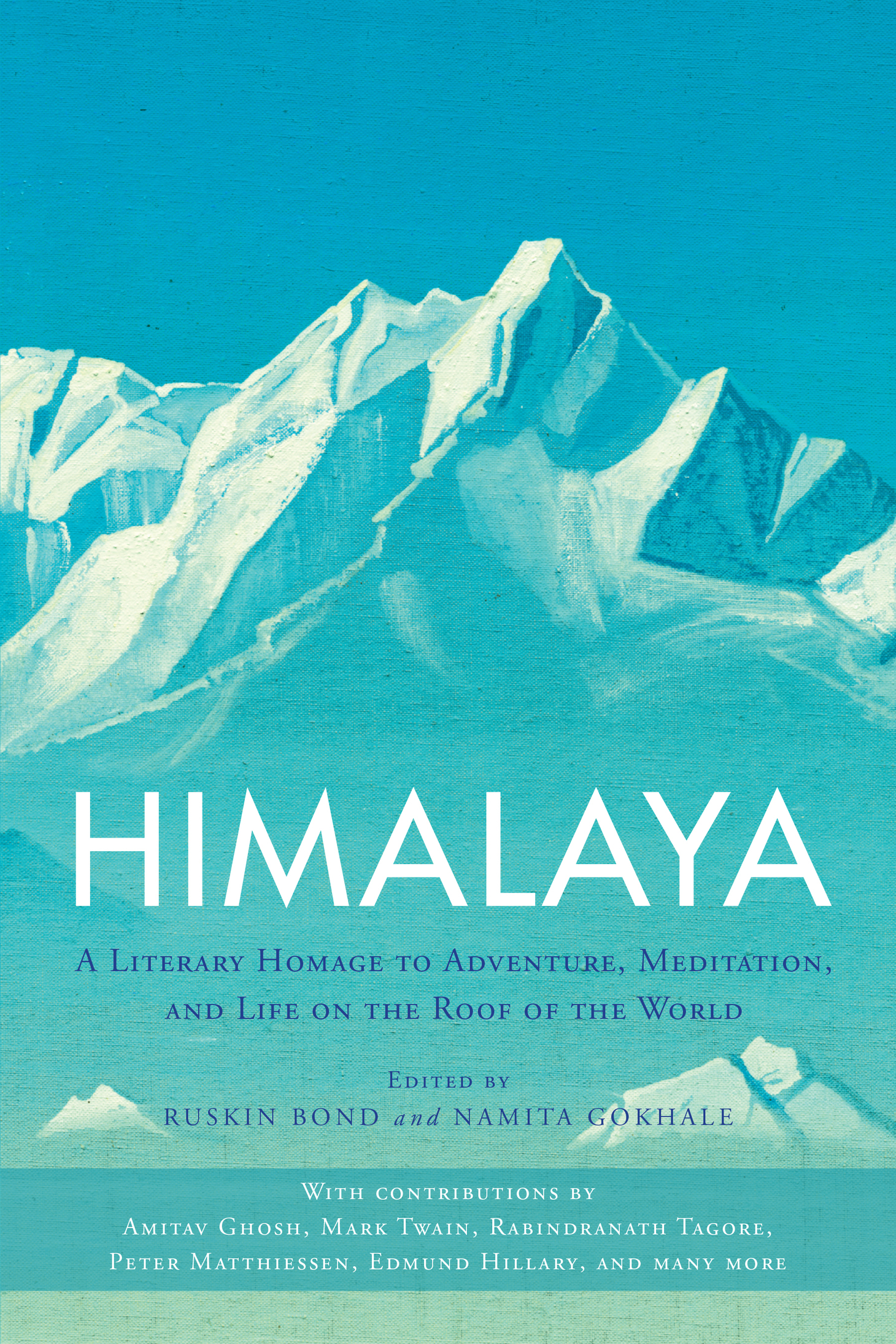

Anthology 2016 by Speaking Tiger

Preface 2016 by Ruskin Bond

Introduction 2016 by Namita Gokhale

Frontispiece by Karan Shah, from larger photo A View of the Dengboche Valley, Eastern Nepal.

The copyright for the essays vests with the individual authors or their estates.

This is a slightly abridged version of the book first published in India by Speaking Tiger Publishing in 2016.

Every effort has been made to trace individual copyright holders and obtain permission. Any omissions brought to our attention will be remedied in future editions.

is an extension of the copyright page.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Cover painting: Mount of Five Treasures by Nicholas Roerich

ISBN9781611805901

eISBN9780834841536

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress.

v5.3.1

a

In a thousand ages of the gods I could not tell thee of the glories of the Himalaya

T HE P URANAS

CONTENTS

PREFACE

Some years ago I asked a sailor to describe the most exciting moment of a long sea voyage, and without hesitation he said: My first sight of land! And when I asked a landlocked villager from the mountains to describe his most exciting moment, he replied: The first time I saw the sea.

It is always what lies beyond the horizon that excites us the most, and a seaman has this advantage, that his ship is almost always on the move, from sea to sea, and port to port, while the mountain-dweller is often confined to a particular range or valley. And no matter how beautiful the mountain or the valley, it can grow monotonous after some time. Life in an Indian hill-station is pleasant enough, but two weeks in a remote village at the end of a day-long trek, without electricity or a toilet, and the visitor is soon pining for the fleshpots of the cities.

It isnt surprising, then, that the mountains have been celebrated in prose more often by travelers looking back at a brief adventure than by residents who brave the elements year after year.

The mountainous lands, and the Himalaya in particular, are visited by travelers, explorers, climbers, naturalists, pilgrims. These are people who are evanescent, who come and go and vanish, occasionally giving us their impressions in the books and journals which describe their personal experiences, but they tell us little or nothing about the people who eke out a living on hostile mountain slopes. Only a very few have left enduring and insightful records of their experiences. This is particularly true of those who come in order to conquer mountain peaks. In India, Nepal, climbers turn up every yeara handful once, but now in their hundredstoiling up the slopes of Everest or some other challenging peak and in the process littering the mountain slopes with a trail of garbage as an offering of thanks to the guardian spirits of the Himalaya.

Just occasionally a Frank Smythe comes along, or a Rahul Sankrityayan, with a literary bent and a feeling for both mountains and mountain people. The best of them feature in the first two parts of this collection and make for compelling reading.

There is plenty to choose from, as far as accounts of climbing expeditions go. Edmund Hillary has left us a step-by-hazardous-step description of his ascent of Everest; Sven Hedin is more animated in his narrative. Mallory and Younghusband have had their moments and memories. And we have an extraordinary account of a mutiny on Kanchenjunga by Aleister Crowley, the self-avowed wickedest man in the world, who dabbled in black magic and devil worship and became the subject of several sensational biographies such as The Magical Record of the Great Beast 666. In his account of an abortive attempt at Kanchenjunga he is at pains to present himself as a nice guy and the ideal leader; even so, he was deserted by most of his companions.

Crowley is, however, genuinely funny at times, especially in his description of the Darjeeling climate; and humor is rare in mountain writing. Climbers are apt to become irritable and quarrelsome when they ascend to great heights, and altitude sickness doesnt help.

The inclusion of an essay by Mark Twain provides welcome relief. He genuinely enjoys his hand-car ride down the railway track from Darjeeling, and he conveys his enjoyment to the reader. The surprise, for many readers in English, will be the Hindi writer Rahul Sanskrityayan, who writes with a light touch, moving effortlessly from humor to contemplation.

We should remember that mountains are impersonal. You can climb a peak but you cant possess it. It is simply there, serene and impervious to your love or hate, and it will be there long after you and I are gone. But sometimes they shift, as we saw last year when an earthquake ran through Nepal, flattening dwellings and causing massive avalanches in the higher reaches of the Himalaya. And in the Indian Himalaya, in Uttarakhand, unseasonal heavy rains and flash floods devastated entire villages and townships, changing the landscape and geography of an entire mountain range. It has happened before; it will happen again.

Yes, the mountains are impersonal, for beauty really exists in the beholders eye. Once, admiring the view from a fallow field, I commented on the beautiful sunset. My companion, whose crop had been destroyed in a hailstorm, responded: But you cannot eat sunsets.

The reality of life in the Himalaya has rarely been described as convincingly as in the final part of this volume, which is also my favorite section. Jemima Diki Sherpa, Namita Gokhale, Manjushree Thapa, Bill Aitken, Kirin Narayan, and others bring genuine insight and empathy to their accounts, perhaps because they have lived in the Himalaya themselves. Dom Moraes and Amitav Ghosh prove to be sensitive and intelligent travelers.

Living in the mountains is not a romance for everyone. Wresting a living from the stony, calcified soil does not leave much time for poetry and contemplation. Even so, the mountains have become very personal to me, as they have to other writers who have made their homes here. The changing colors of the hillside, the trees, birds, cicadas, horse-chestnuts, pine cones, cow bells, mule trains, the rain on old tin roofs, the wind in tall deodars, wild flowers in the morning dewall these things are largely personal, appealing to both the spiritual and sensual in our own natures. If we havent produced much literature, it is probably because we have still to come to terms with the majesty of these great mountains. Or, perhaps, the Himalaya have taught us humility. We know that just living, and helping our fellow creatures through life, is enough; it is greater than any art.

R USKIN B OND

Landour, Mussoorie

June 2016

INTRODUCTION

This collection of essays and musings evokes the majesty of the tallest, and youngest, mountains in the worldsky-high peaks that were once the ocean floor.