PRAISE FOR The Last River

[The Last River] belongs to the realm of Jon Krakauers Into Thin Air and Sebastian Jungers The Perfect Storm. It is gripping, insightful, thought-provoking, and it delves into the mindset of extreme adventurers and into the soul of whitewater paddling.

Albuquerque Journal

Suspenseful

USA Today

With his riveting account of the [Tsangpo River] trip, Balf has supplied a smart introduction to the daredevil lifestyle of river runners.

Fortune

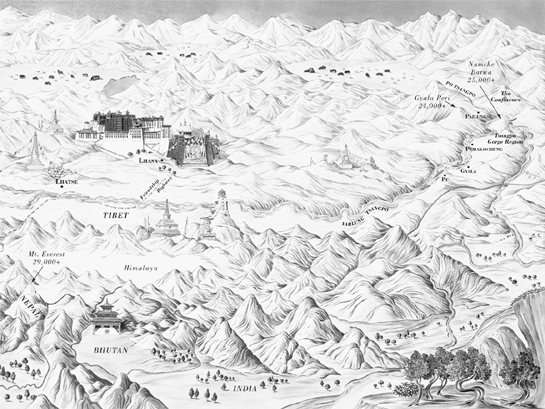

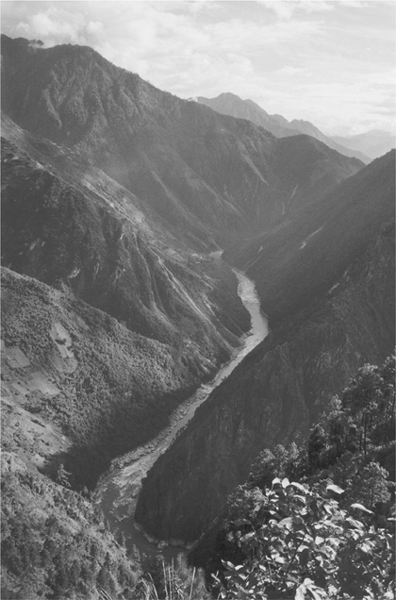

Todd Balfs saga of an assault on the Everest of riversthe fabled Tsangpois a rich and troubling story about the dark side of Americas infatuation with extreme adventure. Its a must-read for anyone who loved Into Thin Airor who might be contemplating that next first descent on a killer river.

Erik Larson, author of Isaacs Storm

Crisp a well-rounded view of the expedition.

Seattle Times

The Last River is high adventure and fine writing. Todd Balf is a splendid storyteller. For anyone captivated by The Perfect Storm or Into Thin Air, The Last River is your kind of book. It is every bit as riveting.

Kevin Baker, author of Dreamland

A tale that rivals Jon Krakauers Into Thin Air. Balf is a consummate craftsman in not only reconstructing the events, but in examining the motivations that propelled these adventurers to take on the deepest gorge on the planet.

Toronto Globe & Mail

A flowing, well placed narrative.

Seattle-Post Intelligencer

A well-balanced tale in which the technicalities of exploring and paddling share space with ruminations on mans spiritual quest and mortality.

Publishers Weekly (starred review)

Fascinating

Dallas Morning News

A sober grabber for the adventure-reading legions.

Booklist

For Patty, Celia, and Henry

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Kristin Kiser for her editorial guidance. To Esmond Harmsworth for his encouragement, and to Patty Adams, Tom Balf, Eugene Buchanan, and Daniel Coyle for their manuscript input. Thanks to Jon Gluck of Mens Journal magazine for his original editorial direction, and more general support, and counsel; to Alex Bhattacharji for his research assistance with the original magazine article; and to Terry McDonell. Thanks to Bill Breen and Fast Company magazine for my temporary leave from usual duties to complete this project. Thanks to Rachel Pace, to David Smith for his copyediting, to Jillian Dunham for fact-checking, to Alex de Steiguer for her photography, to Brad Anderson, and to all my family for their energetic help and especially Nancy Balf, who generously offered her transcription skills.

Finally Id like to thank Connie Gordon and expedition team members Tom McEwan, Roger Zbel, Wick Walker, Jamie McEwan, and Paulo Castillo for their time and detailed recollections. Thanks also to several in the whitewater community: Jan Nesset at Canoe and Kayak magazine, Lisa Fish at U.S.A. Canoe/Kayak, Jason Robertson at American Whitewater Association, and Bruce Lessels and Edward Wilkinson at Zoar Outdoors. Thanks to expedition experts Lukas Blcher, Arlene Burns, and Peter Knowles and to Cathy and Davey Hearn, Evelyn McEwan, Norman Bellingham, Joe Jacobi, John Weld, Andy Bridge, Lecky Haller, and Ryan Bahn. Thanks to Laura Deakin for her concise tutorial in molecular chemistry.

Wan Lin, 1998

Great Falls of the Potomac, August 1975

P REDAWN, THE P OTOMAC R IVER . B OYHOOD FRIENDS W ICK Walker and Tom McEwan, now in their late twenties, and a young tagalong, Dan Schnurrenberger, stumble around their island campsite gathering up gear. They don helmets and spray skirts, grab paddles, and furtively slip into the swift but familiar current. The plan is simple: Before the park service is up and aboutthe Virginia side of the Potomac is part of Great Falls National Parkbefore anyone is up and about, they will paddle upstream a mile and a half to the base of Great Falls, then climb and rope-haul their boats to an overlook where they can scout the crux move of the seventy-five-foot drop one last time.

Great Falls is a twisting, rock-jammed stretch of whitewater where the immense western riversized volume of the Potomac abruptly plunges off the Piedmont Plateau to the coastal plains. Nobody has ever run the vertical falls. The conventional wisdom is that nobody will run the falls. As it is, some seven park visitors each year drown in the rapids. Most of them slip off the gorges high cliffs and are swept into the fierce whirlpools at the bottom of the falls. The thrashing currents can hold a person for a long time. Some victims are never spat out.

And yet Walker and McEwan, hotshot local whitewater racers, have been toying with the idea of a run down Great Falls almost as long as they can remember. Day after day theyd train at O-Deck Rapids and look the short distance upstream to the pounding, mist-shrouded cascade. Could they? At some point the pair began to believe something fundamentally different from what a million or so residents in metro D.C. and every single boater on the Potomac believedthey could. Not only could they run it, but theyd show everyone that their endeavor wasnt the reckless act of thrill-seeking idiots but the work of shrewd, utterly rational individuals. After all, they werent day campers out on a dare. Walker, fair-skinned and block-chested, was a decorated military officer stationed at nearby Fort Belvoir. McEwan, a dark-complected six-footer, was married, with a child on the way. Theyd show that Great Falls was an objective that could be professionally trained and planned for, something they could study and know until the craziness had been wrung from it.

In the years preceding that Sunday in August, they put the falls under their peculiar microscope. As far as they knew, nobody had ever boated off a major falls. They mapped the rivers holes and eddies and drops at a myriad of water levels, then they went out and played guinea pigs at nearby, presumably less sinister, waterfalls. From West Virginia to North Carolina, they boated off increasingly high drops and even swam into the thrashing maelstrom at their base.

In one episode McEwan didnt get flushed out for almost a minute. Part of what they were doing was river morphologyunderstanding the chaotic behavior of a river at its wildest. Part of it was survivalist trainingkeeping it together when every mental impulse screamed for hitting the panic button. Each experience added up to a kind of blueprint for what to do, or, more accurately, what not to do when boating off a vertical fall. By the time they scrambled up the cliffs above the first twenty-five-foot drop, the Spout, they had a sense theyd done their homework, cracked the code. Moreover, they had a belief that theyd come to understand Great Falls (and, by extension, any other similarly monstrous and mythic river) for what it truly wasrocks and water, as Tom put it. What it WAS. Not what their fears or other peoples fears told them it was. And what it was was runnable.