THE SIEGE OF SHANGRI-LA . Copyright 2002 by Michael McRae. All

rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted

in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including

photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval

system, without written permission from the publisher. For information,

address Broadway Books, a division of Random House, Inc., 1540

Broadway, New York, NY 10036.

BROADWAY BOOKS and its logo, a letter B bisected on the diagonal, are

trademarks of Broadway Books, a division of Random House, Inc.

Visit our website at www.broadwaybooks.com

First edition published 2002

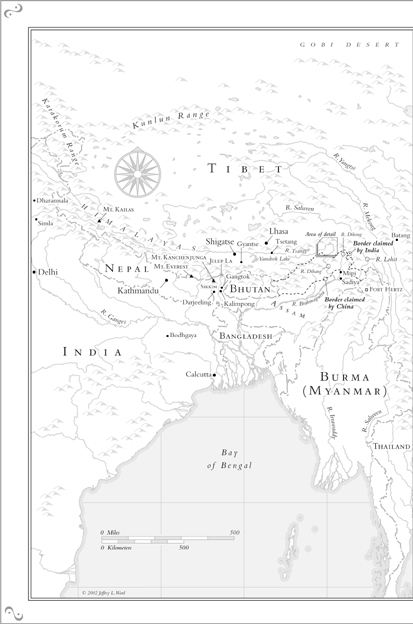

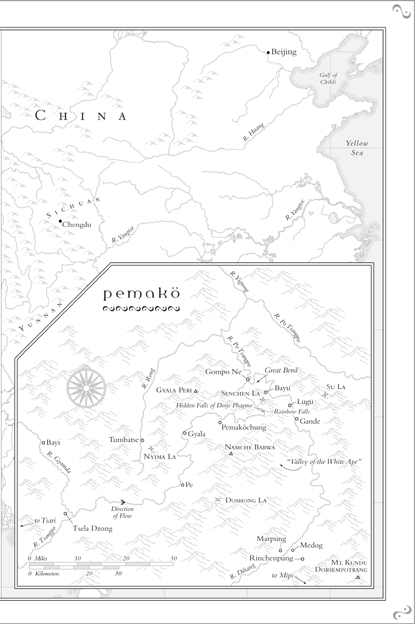

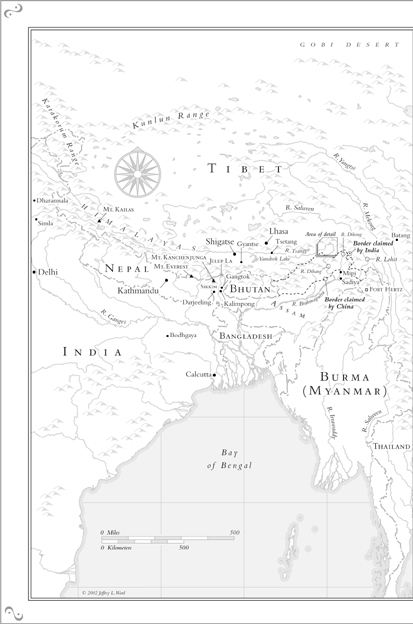

Map designed by Jeffrey L. Ward

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

McRae, Michael J.

The Siege of Shangri-La : the quest for Tibets sacred hidden

paradise / Michael McRae

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

1. Tibet (China)Description and travel. 2. Brahmaputra River

Description and travel. I. Title: Quest for Tibets sacred hidden

paradise. II. Title.

DS786 .M387 2002

951.5dc21 2002025871

eISBN: 978-0-7679-1392-8

v3.1_r1

For Ginny

my divinely feminine adventurer,

with love and appreciation

Contents

Prologue

The Riddle of the Tsangpo

Part One

The Lost Waterfall

Part Two

Perceptions of Paradise

Part Three

Beyond Geography

Epilogue

After the Flood

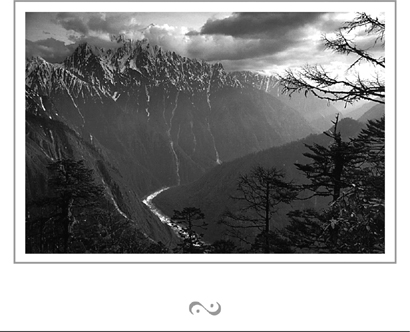

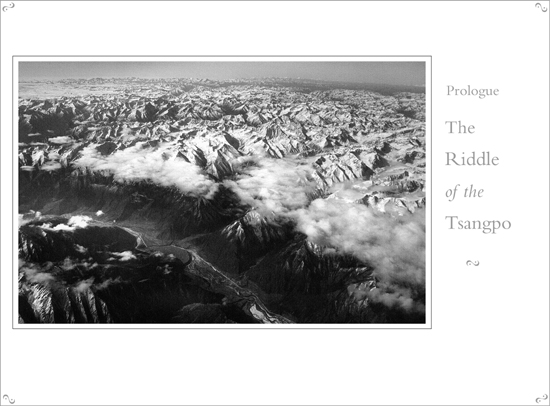

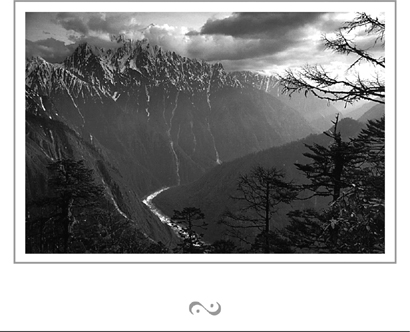

Opening page: Vale of mystery: the heart of Tibets Tsangpo River Gorge, now thought to be the worlds deepest. To nineteenth-century geographers, the gorge was one of the last remaining secret places of the earth, which might perhaps conceal a fall rivaling Niagara or Victoria Falls in grandeur (British political officer, spy, and explorer Capt. F. M. Bailey, 1913). Photo by David Breashears.

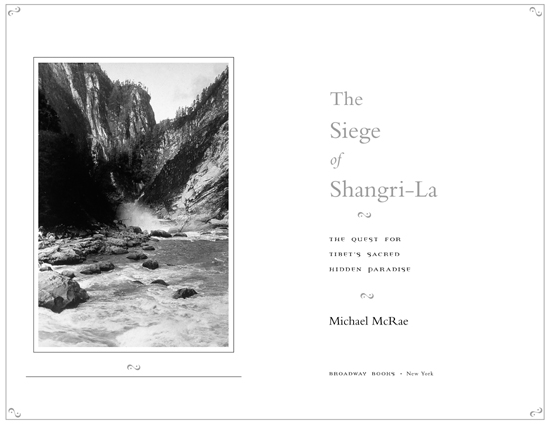

Title page: Rainbow Falls as seen from above. Until the modern era, daunting terrain beyond this point turned back all Westerners who attempted to forge through the Tsangpos inner canyon, including the steel-willed plant hunter Francis Kingdon-Ward on his 1924 Riddle of the Tsangpo Gorges Expedition. Photo by Francis Kingdon-Ward, from the collection of the Royal Geographical Society.

Previous page: The southeastern Himalayas with the Tsangpo River in the foreground. After disappearing into these snow-clad mountains at an elevation of about ten thousand feet, the river emerges in the jungles of northern India at five hundred feet, having lost more than nine thousand feet in less than two hundred river miles. Photo by Gordon Wiltsie.

D URING THE NINETEENTH centurys Golden Age of Exploration, the West had a peculiarly Eastern way of relating to far-flung landscapes. The worlds remote and uncharted places were initially conjured up in an imaginative processa kind of geographical meditationbefore Europeans went out and discovered them. Often based on rumors or sketchy reports from early travelers, the envisioned landscapes gained form and definition through the process of surveying and mapping. In time, after repeated surveys, the worlds white spaces or blanks on the map, as they were called, left the realm of imaginative geography and became real.

It was the era of scientific discovery, and the great explorers of the ageLivingstone, Burton, Speke, and Stanley in Africa; Amundsen, Scott, and Shackleton at the poles; and, later in the century, a wave of Himalayan explorerswere the high priests of geography. The maps drawn by these intrepid travelers were to exploration what scriptures were to theology: the font of authority for ascertaining truths distantly glimpsed, according to historians Karl Meyer and Shareen Brysac.

But an Eastern philosopher might offer that such an empirical method of knowing the world stops short of real discovery, that once the newly found landscape is defined through rational observation, it becomes separate from us, and we lose a vital connection to it. In Tibetan Buddhism, for example, the distinction between the physical landscape and the inner landscape of the mind is blurred. Exploring the former can become a journey into the latter, particularly if the landscape is a sanctified power place. Geography in such places is said to exist on four levels. The physical realm is obvious to all, but the inner, hidden, and paradisiacal secret levels are accessible only to adepts who are spiritually prepared, and only when the time is auspicious. For them, the journey through the physical landscape becomes an allegory for the path to enlightenment itself.

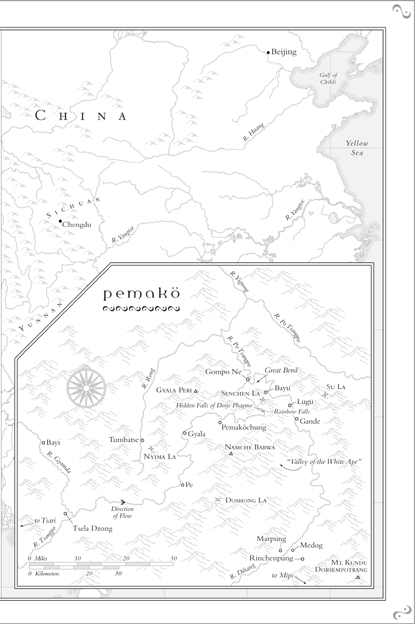

This is the story of the Wests discovery of one such power place, the Yarlung Tsangpo River Gorge of southeastern Tibet. Here, after meandering for nearly a thousand miles across the breadth of the Himalayas, the Tsangpo plunges off the Tibetan Plateau and disappears into a knot of lofty peaks. In the course of less than two hundred miles, the river loses some nine thousand feet of elevation before it spills onto the plains of northern India, where it is renamed the Brahmaputra.

A century and a half ago, geographers were as puzzled about what happened to the Tsangpo after it left the plateau as they were about the source of the Nile. Did it feed the Brahmaputra, as we now know, or did it flow into any of half a dozen other rivers that spill down from Tibet and crash through the jungles east of the Himalayas, in Burma and China? Within about two hundred miles of the Tsangpo are the Yangtze, Mekong, Salween, and Irrawaddy, as well as lesser rivers such as the Lohit, Dibang, and Dihang. The four major rivers bore through the mountains, forming deep, narrow, impassible canyons and, at lower elevations, they rush through subtropical forests with a rich diversity of flora and fauna, from orchids to red pandas and, in the lower Tsangpo Gorge, the last of Tibets tigers, believed to number fewer than twenty.

Until the middle of the nineteenth century, the Tsangpo Gorge and much of the surrounding region remained a geographical black hole within a black hole: a place of extreme climate and terrain, populated by fierce tribes, and lying within the borders of Tibet, which was then closed to all outsiders. The British had more than an academic interest in penetrating the canyon; there were also strategic and commercial imperatives. At the time, Britain was engaged with Russia in a geopolitical contest called the Great Game. The intrigue had opened earlier in the century when British agents found evidence that Russian emissaries had been in Tibet. Fearing that the tsar would overrun the country and use it as a launching pad to gain control of Central Asia and the crown jewel of India, Britain sent its own spies into Tibet to learn the lay of the land and gather intelligence. The native surveyors, recruited in India and trained by British officers, were the famed pundits (a Hindu word for learned man). They were sent into Tibet disguised as religious pilgrims to chart the course of the Tsangpo and determine whether, in fact, it was connected to the Brahmaputra. If so, the river could be followed upstream from India, and both British troops and traders would have a new route over the Himalayas and into Tibet.