The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

1998, 2018 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published in 1998

Paperback edition 1999

First edition, with enlarged text, published 2018 by the University of Chicago Press

Printed in the United States of America

24 23 22 21 20 19 18 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-48548-5 (paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-48551-5 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/[9780226485515].001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

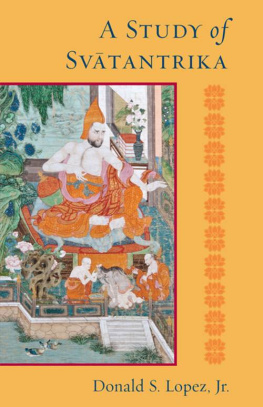

Names: Lopez, Donald S., Jr., 1952 author.

Title: Prisoners of Shangri-La : Tibetan Buddhism and the West / Donald S. Lopez, Jr.

Description: Twentieth anniversary edition, with a new preface. | Chicago : The University of Chicago Press, 2018. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017032242 | ISBN 9780226485485 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226485515 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: BuddhismChinaTibet Autonomous Region.

Classification: LCC BQ7604 .L66 2018 | DDC 294.3/923dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017032242

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

TWENTIETH ANNIVERSARY EDITION, with a NEW PREFACE

PRISONERS of SHANGRI-LA

TIBETAN BUDDHISM and the WEST

Donald S. Lopez, Jr.

THE UNIVERSITY of CHICAGO PRESS

CHICAGO and LONDON

for TOMOKO

Preface to the Twentieth Anniversary Edition

The term Shangri-La was coined by James Hilton to name a mythical land in his 1933 novel Lost Horizon. Twenty years ago, when Prisoners of Shangri-La was first published, Shangri-La still remained a domain of the imagination. Yet the search for Shangri-La has not ceased, and some claim to have found it, even putting it on a map: in 2001, to encourage tourism, a Tibetan town in Yunnan Province in China was officially renamed Shangri-La.

In April 1944, just a few years after Hiltons novel was made into Frank Capras classic film Lost Horizon, the renowned Austrian mountain climber and SS Sergeant Heinrich Harrer escaped from a British detention camp in India. Making use of their alpine skills, he and his fellow mountaineer Peter Aufschnaiter crossed the Himalayas into Tibet, where they planned to stay until the end of the Second World War. Instead, they remained there much longer; Seven Years in Tibet would become the title of Harrers bestselling 1952 memoir, itself made into a film in 1997, starring Brad Pitt as Harrer.

Writing in his diary on February 13, 1946, Harrer reports that at a party in Lhasa, he met a Mongolian Lama, who spoke English and who is doing translations and who is also writing poetry. His name is Chmphel. Harrer says that Chmphel told him that he had recently been paid by the British to translate a biography of the thirteenth Dalai Lama and that the translation had been sent to Sir Charles Bell (18701945), the long-serving British political officer in Sikkim who had retired to Canada. Harrer was wrong about the ethnicity of his interlocutor. He was from Amdo, and his name was Gendun Chopel (19031951). He had returned to Lhasa in the summer of 1945 after twelve years in India.

The translation of the Tibetan biography, entitled Wondrous Garland of Jewels (Ngo mtshar rin po chei phreng ba), and its dispatch to Charles Bell is confirmed by Bell himself in the preface to his famous biography of the thirteenth Dalai Lama, Portrait of a Dalai Lama. There, Bell explains,

A biography of the late Dalai Lama was compiled under the orders of the Tibetan government. It was completed in February, 1940, between six and seven years after the Dalai Lamas death in December, 1933 and is entitled The Wonderful Rosary of Jewels. The Regent was so good as to give me a copy of it, printed

Bell

It seems that the translation was

Portrait of a Dalai Lama was published in London in 1946, the year of Harrers conversation with Gendun Chopel. That same year, in Paris, Georges Bataille (18971962) began work on a series of essays that would be published in 1949 as The Accursed Share (La part maudite), in which he argues that the economies of all societies generate an excess that cannot be put to productive use and must therefore be somehow wasted, most often in weapons of war but also in luxury goods, religious spectacles, games, and massive monuments. He offers a number of case studies, including Aztec sacrifice, the potlatch of the Pacific Northwest, Soviet industrialization, and the Marshall Plan. Part 3 of The Accursed Share is entitled The Society of Military Enterprise and the Society of Religious Enterprise, with the first represented by Islam and the second by Tibetan Buddhism, or, as he calls it, Lamaism. In a chapter of eighteen pages, Bataille offers an analysis of Tibetan society. He does this based on a single source: Sir Charles Bells Portrait of a Dalai Lama.

Batailles audacity in providing a grand analysis

Bataille offers a brief sketch of Tibetan history, explaining that Tibet chose monks over a king, creating a system in which all prestige was invested in lamas and military force was abandoned. The Dalai Lama, although head to defend the dharma.

For Bataille, the effort was doomed from the start. Using what he acknowledges are very rough estimates from Bell, he states that one in three adult males were monks and that between 5 and 10 percent of the population of Tibet were religious persons. Citing Bells estimate of the annual expended revenues, he finds that, in theory, the total budget of the Church would

This brings him to the accursed share, the surplus

There is much to question in Batailles argument. In the years both before and after the thirteenth Dalai Lamas death in 1933, Tibet was a far less closed society than Bataille presents it to be. Yet it is the case that much of the Tibetan economy was controlled, in one way or another, by Buddhist institutionsfrom the massive generation of wealth by monasteries, to the state appropriation of funds for the performance of rituals and the maintenance of temples and the icons they housed, to the fact that monasteries served as major landholders and lending institutions in much of Tibet.

Bataille published The Accursed Share in 1949, one year before troops of the Peoples Liberation Army crossed into Tibetan territory. Although he alludes, almost mockingly, to Buddhist prophecies of invasion, he does not cite the thirteenth Dalai Lamas own prophecy, which was translated in Bells biography. There, warning of the threat of Communism, the Dalai Lama writes (in Bells translation),

Unless we can guard our own country, it will now happen that the Dalai and Panchen Lamas, the Father and the Son, the Holders of the Faith, the glorious Rebirths, will be broken down and left without a name. As regards the monasteries and the monks and nuns, their lands and other properties will be destroyed.

Like the prophecies mentioned by Bataille, this one came true; foreigners conquered Tibet. As was not prophesied, the foreigners have stayed long. In the period since the Chinese annexation of Tibet, does Batailles theory retain any purchase? If so, what has become of Tibets accursed share?

In 1961, two years after the Dalai Lamas flight into exile, there was an extraordinary meeting in Dharamsala of many of the high-ranking lamas who had escaped from Tibet. There is a famous black-and-white group photograph that records something that had never occurred before in Tibetan history: the Dalai Lama, the Karmapa, Sakya Trizin, and a high Nyingma lama (in this case, Dudjom Rinpoche) seated side by side. Behind them are many of the most renowned figures to have escaped from Tibet, including Kalu Rinpoche and Dilgo Khyentse. This was a highly significant event and one deserving of full study. One of the purposes of the meeting was to decide how best to preserve Tibetan Buddhism in exile.

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).