This book was written with the generous support of a fellowship from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, augmented by funding from the College of Literature, Science, and the Arts at the University of Michigan. Initial research on the project was conducted while I was a scholar in residence at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles. Among its excellent staff, I would like especially to thank Sabine Schlosser, Jasmine Lin, and George Weinberg. My research assistant at the Getty, Candace Weddle, provided invaluable and uncomplaining support in accurately transcribing long passages from arcane texts. At the University of Michigan, Anna Johnson checked the accuracy of those passages and offered useful suggestions for the headnotes.

About his origine and native Country, I find the account of those Heathens do not agree.

Engelbert Kaempfer (1727)

After a Christian uprising in Japan in 1637, the shogun banished all Europeans from the country except the Dutch, who seemed interested only in commerce. But he severely restricted their movements, forcing them to live on an artificial island in Nagasaki Bay called Dejima, constructed for this purpose just three years before. The Dutch were the only Westerners allowed on Japanese territory until the arrival of the American commodore Matthew C. Perrys black ships in 1853.

On September 24, 1690, the Dutch ship Waelstrom landed at Dejima. Among its occupants was Engelbert Kaempfer, a German physician employed by the Dutch East India Company. He remained for two years, confined to Dejima except for an annual trip to Edo Castle and an audience with the shogun.

Kaempfers voyage from the Dutch East India Companys headquarters in Batavia (modern Jakarta) to Japan had included a stop in Thailand. Having seen statues of the Buddha in both that country and Japan, Dr. Kaempfer came to the conclusion that the idol worshipped by the Thais represented the same figure as the idol worshipped by the Japanese. Despite the fact that references to the Buddha by Westerners extend back to 200 CE, Kaempfer was among the first to make this startling discovery.

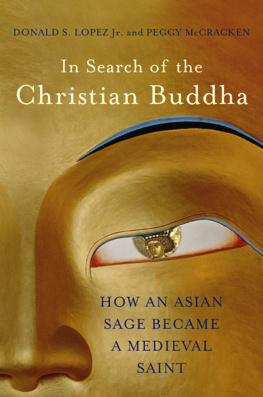

Today, the Buddha is familiar to us as an Indian sage, the founder of a religion so profound that it seemingly transcends the category of religion; perhaps it is a philosophy or simply a way of life. We have forgotten, if we ever knew, that for many centuries Europeans regarded the Buddha with profound suspicion. He was an idol worshipped by heathens, and the man who became that idol was himself a purveyor of idolatry, spreading its pestilence across Asia. And the Buddha was not just one idol. He was many idols known by many names. In retrospect, the reason for the Europeans error is understandable. In the various Asian lands, the Buddha is depicted according to local artistic conventions, and so the Buddha in Thailand looks different from the Buddha in Japan. He is also known by different names in a range of local languages. In the course of this study, I have collected over three hundred European names of the Buddha from the period 2001850names like Bubdam, Chacabout, Dibote, Dschakdschimmuni, Goodam, Nacodon, Putza, Siquag, Thicca, and Xaqua. And the religion that these various idols taught was not called Buddhismthe term did not appear in English for the first time until 1801; it was called idolatry.

Sometime in the late seventeenth century, European missionaries and travelers began to realize that the many idols seen in many nations and the many names recorded in many languages all somehow designated a single figure, though whether it was a figure of myth or of history remained undecided. By the end of the eighteenth century, his identity (and gender) was well established, and it was generally accepted that he had been a historical figure, although his origins were debated. In the nineteenth century, empowered by the new science of philology, European scholars began to decipher Buddhist texts, and the Buddha that we know today was born. We should not immediately conclude, however, that because Europeans now had texts, the Buddha they described was the Buddha of those texts. Indeed, it might be said that in the early decades of the nineteenth century, the Europeans found their own Buddha.

Western references to Buddhism date to the first years of the third century CE, and during the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries, European contact with, and writing about, Buddhism was extensive. Because much of what European writers wrote about the Buddha and Buddhism during this period is considered wrong today, these accounts have largely been forgotten or dismissed. However, they are of great importance for understanding the evolution of our view of the Buddha. This volume, then, is a sourcebook of this fascinating literature. Although it deals only with the figure of the Buddha and not with Buddhism more generally, the available literature is vast, and what is provided here is merely a sampling. It is an anthology of European writings about the Buddha, beginning with Clement of Alexandria around 200 and ending with Eugne Burnouf in 1844.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).