Foreword

by His Holiness the Dalai Lama

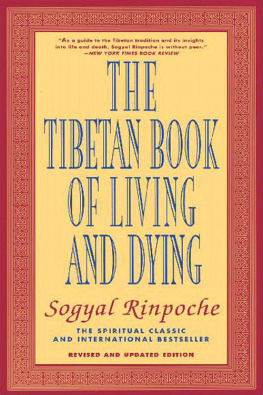

IN THIS TIMELY BOOK, Sogyal Rinpoche focuses on how to understand the true meaning of life, how to accept death, and how to help the dying, and the dead.

Death is a natural part of life, which we will all surely have to face sooner or later. To my mind, there are two ways we can deal with it while we are alive. We can either choose to ignore it or we can confront the prospect of our own death and, by thinking clearly about it, try to minimize the suffering that it can bring. However, in neither of these ways can we actually overcome it.

As a Buddhist, I view death as a normal process, a reality that I accept will occur as long as I remain in this earthly existence. Knowing that I cannot escape it, I see no point in worrying about it. I tend to think of death as being like changing your clothes when they are old and worn out, rather than as some final end. Yet death is unpredictable: We do not know when or how it will take place. So it is only sensible to take certain precautions before it actually happens.

Naturally, most of us would like to die a peaceful death, but it is also clear that we cannot hope to die peacefully if our lives have been full of violence, or if our minds have mostly been agitated by emotions like anger, attachment, or fear. So if we wish to die well, we must learn how to live well: Hoping for a peaceful death, we must cultivate peace in our mind, and in our way of life.

As you will read here, from the Buddhist point of view, the actual experience of death is very important. Although how or where we will be reborn is generally dependent on karmic forces, our state of mind at the time of death can influence the quality of our next rebirth. So at the moment of death, in spite of the great variety of karmas we have accumulated, if we make a special effort to generate a virtuous state of mind, we may strengthen and activate a virtuous karma, and so bring about a happy rebirth.

The actual point of death is also when the most profound and beneficial inner experiences can come about. Through repeated acquaintance with the processes of death in meditation, an accomplished meditator can use his or her actual death to gain great spiritual realization. This is why experienced practitioners engage in meditative practices as they pass away. An indication of their attainment is that often their bodies do not begin to decay until long after they are clinically dead.

No less significant than preparing for our own death is helping others to die well. As a newborn baby each of us was helpless and, without the care and kindness we received then, we would not have survived. Because the dying also are unable to help themselves, we should relieve them of discomfort and anxiety, and assist them, as far as we can, to die with composure.

Here the most important point is to avoid anything which will cause the dying persons mind to become more disturbed than it may already be. Our prime aim in helping a dying person is to put them at ease, and there are many ways of doing this. A dying person who is familiar with spiritual practice may be encouraged and inspired if they are reminded of it, but even kindly reassurance on our part can engender a peaceful, relaxed attitude in the dying persons mind.

Death and Dying provide a meeting point between the Tibetan Buddhist and modern scientific traditions. I believe both have a great deal to contribute to each other on the level of understanding and of practical benefit. Sogyal Rinpoche is especially well placed to facilitate this meeting; having been born and brought up in the Tibetan tradition, he has received instructions from some of our greatest Lamas. Having also benefitted from a modern education and lived and worked as a teacher for many years in the West, he has become well acquainted with Western ways of thought.

This book offers readers not just a theoretical account of death and dying, but also practical measures for understanding, and for preparing themselves and others in a calm and fulfilling way.

June 2, 1992 The Dalai Lama

IT IS NOW TEN YEARS SINCE The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying was first published. In this book, I endeavored to share something of the wisdom of the tradition I grew up in. I sought to show the practical nature of its ancient teachings, and the ways in which they can help us at every stage of living and dying. Many people, over the years, had urged me to write this book. They said that it would help relieve some of the intense suffering that so many of us go through in the modern world. As His Holiness the Dalai Lama has pointed out, we are living in a society in which people find it harder and harder to show one another basic affection, and where any inner dimension to life is almost entirely overlooked. It is no wonder that there is today such a tremendous thirst for the compassion and wisdom that spiritual teachings can offer.

It must have been as a reflection of this need that The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying was received with such enthusiasm around the world. At first I was astonished: I had never expected it to have such an impact, especially since at the time of writing this book, death was still very much a subject that was shunned and ignored. Gradually, as I traveled to different countries, teaching and leading workshops and trainings based on the teachings in this book, I discovered the extent to which it had struck a chord in peoples hearts. More and more individuals came up to me or wrote to tell me how these teachings had helped them through a crisis in their lives or supported them through the death of a loved one. And even though the teachings it contains may be unfamiliar, there are those who have told me they have read this book several times and keep returning to it as a source of inspiration. After reading The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying, a woman in Madras in India was so inspired that she founded a medicaltrust, with a hospice and palliative care center. Another person in the United States came to me and said she was baffled by how a mere book could have, in her words, loved her so completely. Stories like these, so moving and so personal, testify to the power and relevance of the Buddhist teachings today. Whenever I hear them, my heart fills with gratitude, both to the teachings themselves and to the teachers and practitioners who have undergone so much in order to embody them and hand them on.