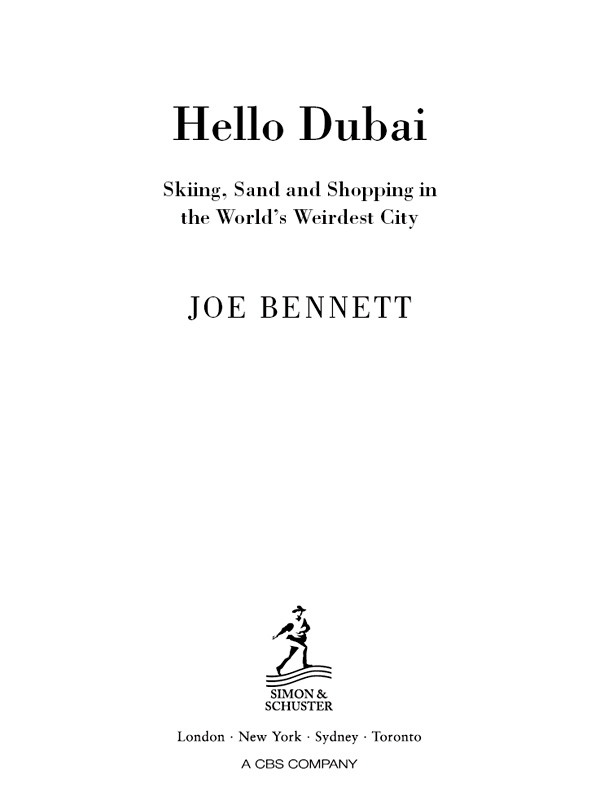

Born in Eastbourne in 1957 and educated at Brighton and Cambridge, Joe Bennett taught English in a variety of countries before becoming a newspaper columnist and writer of travel books. He lives in Lyttelton, New Zealand.

Also by Joe Bennett

Bedside Goats and Other Lovers

Fun Run and Other Oxymorons

A Land of Two Halves

Mustnt Grumble

Love, Death, Washing-Up, etc.

Where Underpants Come From

First published in Great Britain in 2010 by Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

A CBS COMPANY

Copyright 2010 by Joe Bennett

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention.

No reproduction without permission.

All rights reserved.

The right of Joe Bennett to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

1st Floor

222 Grays Inn Road

London

WC1X 8HB

www.simonandschuster.co.uk

Simon & Schuster Australia

Sydney

A CIP catalogue copy for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-84737-674-9

eBook ISBN: 978-1-84983-830-6

Wilfred Thesiger excerpts are taken from Arabian Sands, published by Penguin Classics, 2007

Typeset in Palatino by M Rules

Printed in the UK by CPI Mackays, Chatham ME5 8TD

For Albert Arriola

Acknowledgements

Id like to thank my hosts in Dubai and Al Ain for their generosity and kindness. And also their friends and the many others who answered my persistent questions with such tolerance and patience.

Introduction

W hen I was at school I hadnt heard of Dubai. If youd asked me where it was I would have guessed Africa. I wouldnt have been far wrong. But if Id guessed India I wouldnt have been far wrong either, or Asia, or even Europe. Dubai isnt far from anywhere. That centrality has served it well.

I hadnt heard of Dubai forty years ago because there wasnt much to hear of. It was just a hot little port on the Arabian Gulf. People had lived there for hundreds of years. Theyd put to sea and traded and eaten a lot of fish, but they hadnt multiplied much because the land they inhabited was desert. Offering only dates, a bit of meat and a few sources of fresh water, the desert kept the people skinny and pinned them to the coast. Dubai, like Arabia in general, was a quiet place.

Time was, however, when Arabia in general had run the world. In the middle of the eighth century, only a hundred years after the birth of Islam, the Arabian Empire was larger than the Roman Empire had ever been. It embraced Spain and about two thirds of the Mediterranean seaboard. It had swept up through what is now Turkey. It had penetrated the Indian subcontinent. It had reached the great mountain ranges of Central Asia and had even clambered over them into what is now western China. Arabia, in short, was the great world power and Islam was the great world religion.

The world owes much to that empire. It kept learning alive in the West. When Europe was benighted under illiterate tribal thugs, the Arab world was fostering science and philosophy, translating classical texts, importing mathematics from India and adapting technology from the Far East.

But gradually the empire declined as empires do and Arabia settled back into what looked like a terminal snooze. Then, in the twentieth century, oil happened. It happened to Dubai as it happened to much of the Middle East. Dollars rained down. If it hadnt been for oil, Dubai would still be snoozing in the sun and Id still think it was in Africa.

The places that found oil, or had it found for them, reacted variously. Many leaders gorged on the wealth it brought, but Dubai proved wiser. Perhaps because it didnt have as much oil as others had, it foresaw a time when it wouldnt have any. So Dubai set about creating something that would endure when the party was over. The result was the city that seemingly grew overnight.

In only a few decades Dubai has become a hub of global trade and global finance. It has developed a tourism industry. It has erected buildings that everybody knows. And it has attracted people from almost every country on earth. Since 1960, Dubais population has multiplied about twenty-fold.

And all this has been accomplished peaceably. Though it is situated in the worlds most volatile region, where blood has been spilt throughout my lifetime and looks unlikely to stop being spilt any time soon, Dubai has fought no wars and suffered no terrorism. In a time of increasing tension between the Muslim world and the nominally Christian one, Dubai has somehow stood aside from the fray.

On the face of it, Dubai would seem like a model for the way ahead, but its critics are abundant and strident. As the American economic crisis spread across the world and put the wind up capitalism, there came a flood of articles about Dubai that oozed hatred. The writers, most of them British, saw Dubai as the emblem of a rotten world, a world that was imploding. Dubai was brash. Dubai was cruel. Dubai was exploitative. Dubai was a speculative bubble. Dubai, in short, was plain bloody horrible, and if the economic crisis killed off Dubai it would at least have done one good thing.

In the Independent Johann Hari called Dubai a city built on credit and ecocide, suppression and slavery.

In the Sunday Times, Rod Liddle asserted that Dubai was a slave state and not too far removed from a pre-war Third World fascist theocracy.

And Simon Jenkins of The Times went in for prophecy. The dunes will reclaim the soaring folly of Dubai, he wrote. Dubai was the last word in iconic overkill, a festival of egotism with humanity denied.

I joined the chorus in a small way myself. In a newspaper column in 2008 I called Dubai the spiritual home of suit man. Suit man, I suggested, was the business-class executive with the BlackBerry and the Rolex and nothing to contribute to the world except his ability to turn one dollar into two without doing anything useful.

And on what evidence did we so despise Dubai? Well, I cant speak for the others, but Id spent four days there one summer a few years back. During those four days, the heat was too fierce to do anything much but shift from air-conditioned hotel room to air-conditioned bar. In other words I knew next to nothing of the place. My opinion was prejudice.

That prejudice had been partly fostered by a patrician Englishman called Wilfred Thesiger. Thesiger was an oddball, a loner and an explorer. In the 1930s and 40s he made repeated treks across the sands of the Arabian Peninsula, including two crossings of the Empty Quarter, a terrifying blank on the map. Like his hero, T.E. Lawrence, he dressed as an Arab and he travelled in the company of Arabs, the tribal nomads known generically as the Bedouin. Born freebooters, he called them, contemptuous of all outsiders, and intolerant of restraint, and he painted a picture of them as a heroic race; but also a doomed one, for oil had already been found in the region. Modernity was sniffing round the edges of the desert. It would seduce and destroy, predicted Thesiger, an ancient and noble way of life.

Thesiger died only a few years ago. As an old man he was invited to return to the United Arab Emirates and see the soaring new cities of Dubai and Abu Dhabi. He hated them. He described them as an Arabian nightmare, the final disillusionment. Its an old mans lament, of course, for what was, for a vanished past... and a once magnificent people. But its a persuasive lament nonetheless. From the comfort of ones armchair and with a supermarket just down the road, it is easy to view modern Dubai as the triumph of shallow materialism over ancient nobility, of consumption over honour, of shopping over endurance.

Next page