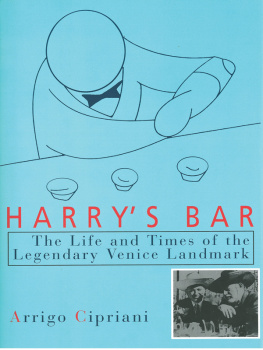

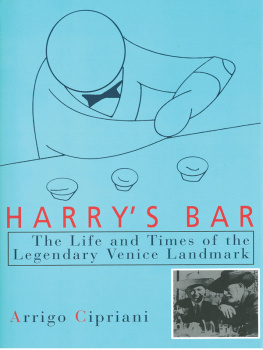

Also by Arrigo Cipriani

Heloise and Bellinis

HARRYS BAR

The Life and Times of the Legendary Venice Landmark

Arrigo Cipriani

ARCADE PUBLISHING NEW YORK

Copyright 1996, 2011 by Arrigo Cipriani

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Arcade Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.arcadepub.com.

The photographs on the third page of the photo insert showing the front window and entrance of Harrys Bar are by Denholm Jacobs III.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-61145-320-1

Printed in the United States of America

CONTENTS

SERVICE

There is soul, and there are things.

Imagine a world made up only of objects,

A world of idle tools,

A restaurant of nothing but tables and chairs,

A large empty theater, or a deserted plaza in summer.

They cry out for the service of man,

The service to give them life.

We call on man to display his splendid capabilities.

And

We observe with undivided attention,

Because

The little nuances in the quality of his service

Give a flawless measure of his mind,

They tell us frankly what his soul is worth,

Because,

To serve is first to love.

HARRYS BAR

O NE VERY MUGGY SUMMER DAY in the late 1960s, I went to see my father in his home in the Valsugana Mountains near Trento, where in his later years he sometimes took a months vacation. I had been running Harrys Bar for a little over ten years, and, in theory at least, my father was no longer involved in the day-today business of the bar he had founded in 1931 and built up to the legendary Venice restaurant it had become. Of course, until the day he died, my father would never accept that he was no longer in charge of Harrys Bar and a good thing it was, too. My father was Harrys Bar. Had he ever really broken all connections with the restaurant, he would have ceased to exist. After he retired from managing Harrys Bar, he still came every day for lunch and was always our most demanding customer the one we tried most to please, and the one who was most sparing with his approval. But a good word from him meant more than all the lavish praise we got from our real customers.

I didnt arrive at Trento until the afternoon, later than I had planned. My father came toward me with that slightly hurried step of his, and he could not refrain from scolding me for my tardiness. I expected that, of course. In the twenty years I ran Harrys Bar while he was alive, I dont think I was late for work a single time. Getting to work by ten oclock in the morning and again at six for the evening meal was like a law of nature in our family, and Im sure that if anyone had ever asked me I would have said that the world would end if I ever arrived for work as much as a minute late. Today, I sometimes think that the strict adherence to a daily routine that I learned from my father, as useful as it is, ruined my taste for discipline forever. For example, soon after he died, I developed an immediate distaste for getting to appointments on time, even for scheduling appointments at all, and its an aversion that has never left me.

That summer day, my father greeted me heartily, then hurried off to the warmest room in the house to see if the Krapfen dough was rising. As everyone in the family knew, fritters had always been my favorite sweet. A moment later he reappeared disgruntled, because the dough had risen too much. As usual, he asked how business had been going while he was away, but this time he did not pay much attention to what I said. He was clearly following his own train of thought elsewhere. We were sitting on the shady side of the house, on a terrace overlooking the meadow, and he suddenly started to talk about Germany, where he had spent his childhood, and about German lieder. And then he started to sing, softly. The lied spoke of an exiles nostalgia for his home in Spain and his all-consuming longing to return.

It was then I discovered a side to my father I had never seen before, and I was glad, because only our family knows how little of it we saw when he was alive. Never had he told me in any explicit way whether I lived up to the expectations he had for the heir to the family business. But on that summer afternoon, I began to realize that I knew him more from what he did over the course of his life than from what he said.

Many of the episodes described in the first part of this book, as told by my father, were events I witnessed too; others he told me about; and still others are part of our family heritage Mama Giulia, my mother, told them to the three of us when we were children. We listened eagerly, as children do to old stories about the grown-ups, as she told them in the evening, while we were alone, and he was at work.

T he first part of the book is told in the first person by my father, Giuseppe Cipriani, the founder of Harrys Bar in Venice.

One morning in 1970 as I was signing some papers at my lawyers office, my right hand suddenly felt very light: the more I tried to hold it down, the more it wanted to rise, as if it had become totally weightless. At the moment it happened, I was rather amused by this strange sensation, and I was far from imagining what it really was. They told me later in the hospital: paralysis.

That was the morning old age hit me. I understood for the first time what it was like to feel tired even after a good nights sleep. It was then I first began very slowly to look back at the past and review the events, the people, and the situations that I had experienced in all those long years since I founded Harrys Bar, and during the time before. The older one gets, the more vivid childhood episodes become, events that are remote in time yet so close in memory you can almost touch them.

My family came from Verona. My father worked as a porter and wore himself out for eighty centesimi a day. He had eight children to support, four boys and four girls.

Those were the years when Italians could obtain the so-called red passport and cross the Atlantic to the United States, jammed into the ships of the Rubattino line. My father in Verona looked for a haven nearer home: Germany.

In 1904 we arrived in Schwenningen am Neckar. My family felt at home at once. The climate and the hilly landscape on the banks of the river were rather similar to those of Verona. And several of our neighbors from Verona were already there, so we settled in easily.

The Germans called us Itakas. They were slow to accept us, but they understood that we meant well. They blew off steam mainly with harmless jokes about Italians that for the most part put us in a good humor too.

Next page