Preface

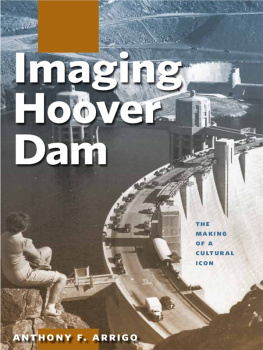

A few years ago I was having a casual conversation with someone about a recent vacation to Nevada and California in which I took a side trip to see Hoover Dam. Little did I know that the seemingly inconsequential exchangea polite how was your trip type of encounter that we have with people all the timewould become the catalyst for several years of research culminating in this book.

My interlocutor, not being from the United States and upon hearing that I'd stopped at Hoover Dam, said, Oh, you must be very proud of that, as an American. This curious response prompted a longer discussion in which we surmised that it probably wouldn't be a stretch to say that, as with Niagara Falls or Mount Rushmore, virtually every American can recognize Hoover Dam and probably knows at least something about it. In fact, it might be the only dam they know by name. The interesting question to me was why.

Intrigued to learn more about the dam, what I quickly found was that, although the history was interesting, what really fascinated me were the images: the riveting depictions of laborers scaling thousand-foot canyon walls to set their blasting caps, the celebratory tone of images showcasing the dam's construction technologies, the pitiable photographs of families living in squalor around the work site. I was struck by the rhetorical features of these images, as well as their ability to instantaneously arrest my attention and speak to me in ways that the text did not or could not. As I began to research the topic in more depth, I found a seemingly endless trovethousands upon thousandsof images of all sorts published in every conceivable medium. It seemed to me that these images had their own story to tell, and the more images I found, the more diverse the story became, in some cases veering wildly from the received history of the dam that I had casually come to know.

One thing that struck me as curious, however, was that although Hoover Dam is a nearly universally knownindeed iconicstructure, I couldn't identify any particular image as the iconic image of the dam. Furthermore, although a few scholars had tackled individual slices of Hoover Dam imagery, no one had attempted a comprehensive analysis of its whole visual repertoire. Consequently, by identifying some key themes that emerge from the vast sweep of Hoover Dam imagery, this work is a step toward filling that gap.

In this book I try to answer the question of how Hoover Dam evolved from a pipe dream of land developers and farmers, to an ambitious civil engineering project in the middle of the Mojave Desert, to the visual and cultural icon that it is today. To do this, in contrast to most scholarship on the dam, I provide a significant shift in focus away from chronicled accounts of how it was built and onto its myriad visual representations. In doing so, I trace how its imagery was deployed through advertising, government propaganda, journalism, and other promotional outlets to shape the public's perception of the project. This discussion ranges from how the dam's imagery reflects the cultural and ecological imperatives that precipitated its construction, to the influence of religious doctrine and the American agrarian movement in the drive to build the dam, to the visual commodification of the project as a way to sell cars, trucks, vacations, and a variety of other goods and services. Ultimately I find that approaching the dam's construction through its imagery juxtaposes its traditional narrative of economic and industrial triumph with an often-contrasting visual counter-narrative of technological domination of both humans and the natural environment.

In order to identify the arguments advanced in the visual-verbal discourses surrounding the dam, this book draws on a variety of primary sources gathered over a several-year period at a number of archives and repositories, including the County of Los Angeles Public Library, the California State Library, the Boulder City Museum and Historical Association, the Nevada State Museum, the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum, the US National Archives, the University of Nevada at Las Vegas (UNLV), the University of Nevada at Reno, Archives of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, the University of Southern California Libraries Special Collections, the Wilson Library at the University of Minnesota, and the Bancroft Library at the University of California at Berkeley.

I would like to acknowledge several people in particular for their help in this endeavor, including Katherine Adams at the County of Los Angeles Public Library; Catherine Hanson at the California History Room, California State Library; Colleen Dwyer, public affairs specialist, US Bureau of Reclamation; David Kessler at the Bancroft Library, University of California at Berkeley; Wendy Stevenson, reference librarian at the State Historical Society of Iowa; Carol Kirsch, supervisor of libraries, special collections, and publications at the State Historical Society of Iowa; and Dace Taube, assistant head of special collections at the Doheny Memorial Library at the University of Southern California. I am indebted to Bernadette Longo, Daniel Philippon, and Larry Baker for their feedback, suggestions, patience, and encouragement. I am also grateful to Beth Ayer for her work in helping me with permissions for many of the images found in this book. Special thanks are in order for Dennis McBride, director of the Nevada State Museum, Las Vegas, who helped me immensely in finding information on Winthrop A. Davis and for his quick and insightful e-mail responses to inquiries on a variety of other topics. Also deserving particular thanks is Laura Hutton, museum coordinator at the Boulder City Museum and Historical Association, who scanned numerous images that you see in this book, and who helped me navigate the wonderful archival materials they have available in Boulder City; this book simply would not have been possible if not for Laura's and the Boulder City Museum's generosity of time and access to their collections. Thanks also go to Delores Brownlee, public services and photographs assistant, at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Special Collections, who graciously coordinated the permissions and reproductions for all of the images you see in this book from the UNLV archives.

I would also like to thank Matt Becker at the University of Nevada Press for his guidance in everything from the publishing process to how to be a professional writer. I would also like to especially thank Richard Graff, who dedicated many, many hours to the initial phase of this project and whose editorial and thematic comments, discerning suggestions, and commitment to excellence made this book far better than I could have ever hoped to accomplish on my own.

Finally, and most important, I would like to acknowledge my loving wife, Sarah, my two wonderful daughters, Bonnie and Clara, and my entire family for their support, interest, and encouragement in this process. I truly could not have finished this book without you.