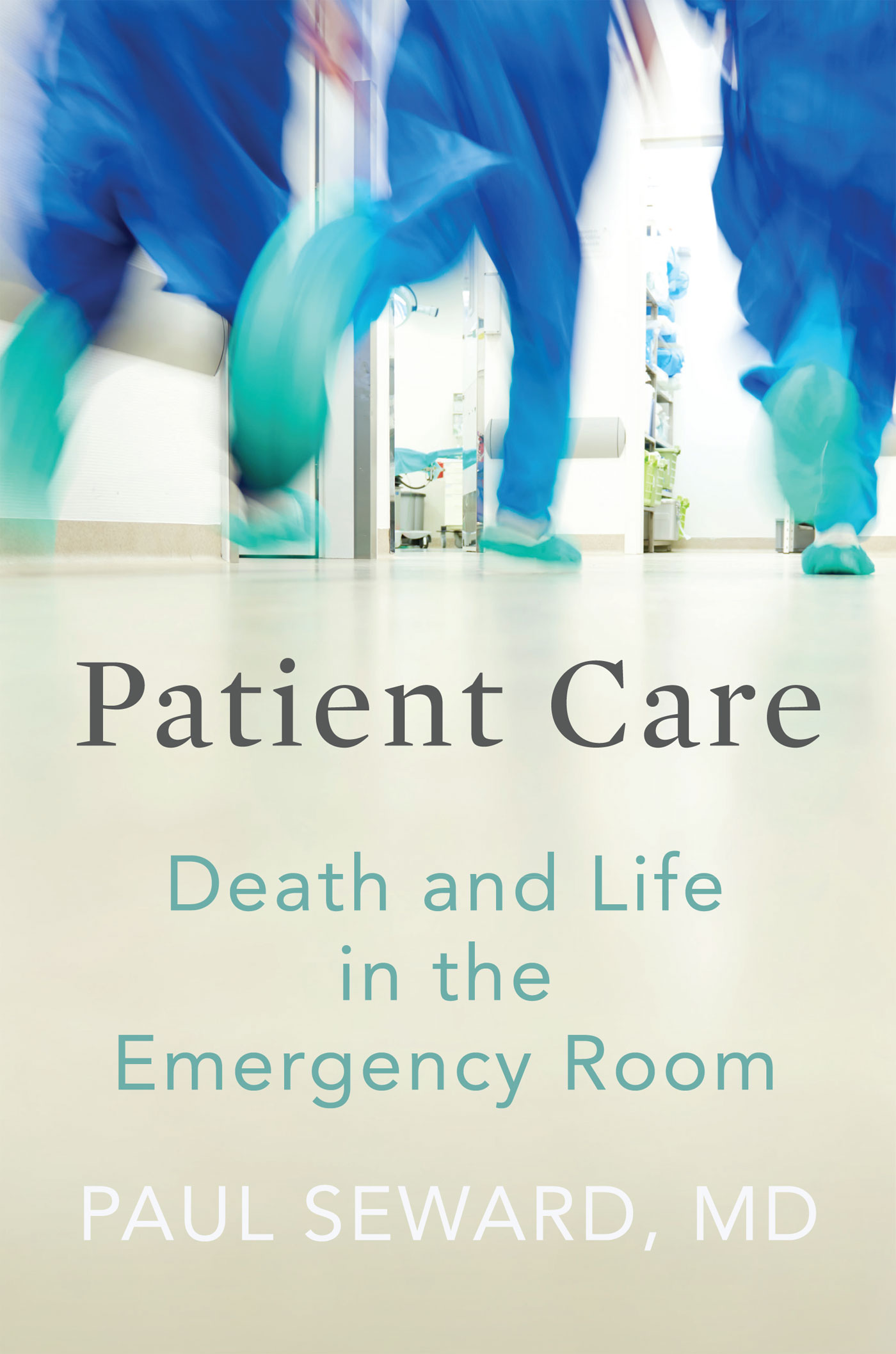

PATIENT CARE

Some names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals.

Copyright 2018 by Paul Seward

First published in the United States in 2018

by Catapult (catapult.co)

All rights reserved

ISBN: 978-1-936787-88-3

eISBN: 978-1-936787-90-6

Book designed by Gopa & Ted2, Inc.

Catapult titles are distributed to the trade by Publishers Group West

Phone: 866-400-5351

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017950940

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

To my teachers , who gave me their knowledge

To my mentors , who gave me their wisdom

To my patients , who gave me their trust

To Linda , who has given me everything

Contents

Preface

M Y GOAL IN writing this book is to tell the reader what its like to work in the emergency room. I dont mean just what happens there; rather I mean what it feels like to work there.

It is true that feelings arise in response to things that happen. Therefore, a book about experiences must also be a book of stories. Even so, as much as possible, the stories in this book are about situations, not merely events. An event is just something that happens; a situation is something that, as it happens, asks for a response from the people who are witnesses.

In light of that distinction, it is important that you, the reader, know that, as much as possible, these stories are true. If they differ from what someone else remembers, that is due to three things: time, perspective, and privacy.

First, these stories occurred during a professional life of well over forty years, in a practice that took me to hospitals in California, Washington, and Arizona on the West Coast, to Georgia in the South, and to New York on the East Coast. I could not possibly remember all the details of those occasions, or the conversations I had. Nonetheless, the core truths of these stories are written from memories that I could not forget if I tried. So if I have fleshed out some details, or put some of my own words in peoples mouths, I have done so not to change the truth of the events but simply to make those truths accessible.

Second, everyone sees from where they stand. Others who were present are assuredly entitled to have differences in what they experienced and remember. However, the only memories I can give you are my own. Those I have rendered as honestly as I can.

Finally, where I could do so, I have made changes that do not alter the meaning of the situation but honor the privacy of the patients and family members who were involved. These are things such as peoples ages, or gender; or the city or time in which the situations took place. Also, I have seen cases like the ones I have chosen many, many times. Thus, if you think that you recognize any particular patient, rest assured, you dont.

With those disclaimers, everything I have put here actually did happen, and for better or worse, I was there in the role I have described. If I have done my job, then what you see is what I saw and what I remember.

However, I have a second goal as well. For me, part of the reason I worked in the ER was that I found it to be a place where I was asked to do the work of living. There was a question on my medical school application: Why do you want to be a doctor? My answer was that, in my opinion, being a doctor was the best way I could think of to do two things: first to study, in depth and in detail, just what a human being really is; and then to act on the implications of what I had learned.

That answer seems pretentious to me now. I was only twenty then, and now, in my seventies, I have seen very clearly that all walks of life offer that challenge and that opportunity. But at that age, I saw it most clearly in medicine. So I went to medical school. And a half century later, I have indeed acquired a few beliefs about the question of who we are and what we should be doing.

The one that is relevant to this book is very simple: I believe that the principal reason we are on this planet is to have our noses constantly rubbed in our obligation to care about people who are strangers to us. When I look around, I see a world in which, in every instant of our lives, we are unavoidably confronted with the question of whether the quality of other peoples lives and experiences is as important as our own. If we think so, we will act in one way; if we do not, then we will act in another.

But why is caring about strangers so difficult? Are we not hardwired for love? We naturally love our children and our family, we care about our friends. Of course we do. For almost all of human history, those were the only people we ever encountered. We had to love them to survive.

Yet I would argue that precisely because those behaviors are so hardwired, they are not matters of choice. Love, as a choice, enters the picture only when we encounter a stranger. Our instinct to care for our family and our tribe does not extend to them. That kind of caring must be learned. And, in my opinion, the ER is a place that, if you are paying any attention at all, will teach you that lesson.

Butand this is the final and most critical pointthe belief that we are here to learn to love others not only motivates such choices, it is created by them. Yes, certain environments teach some values better than others. But like any other school, the most important part of learning is the desire of the pupil to become better than they already are.

For much of my life, I have tried my best to enact the role of a caring physician. I have no idea whether I have succeeded at all in becoming one, but I do know what it felt like to try.

PATIENT CARE

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER ONE

The Young Mans Friend

I T WAS MIDAFTERNOON . As I recall, it was not a particu-larly busy one.

The chart was not the next one in the rack; it never even got to the rack. Instead, while I was writing a note about a patient whose hand laceration I had just closed, the nurse covering the back hall came up front to the main nurses station where I was working. She didnt say anything. She just stood there waiting silently, arms folded over her chest, holding a chart within them.

I finished the sentence I was writing and looked up. What do you need? I asked.

I wonder if you could come and see this one now. Hes pretty sick. I stood up at once.

I knew that his being sick wasnt the only reason she had come to the front. After all, this was an emergency room. Most people were sick, or at least thought they were. Furthermore, patients who were critically unstable went to the resuscitation rooms, not to the back hall. But if she had wanted to say more at that point, she would have done so. I just said Okay, took the chart, and followed her.

On the way, I looked over what was written: a twenty-two -year-old man, resident of a nursing home; normally in a chronic vegetative state; noted this morning to have a fever and be less responsive than his baseline level, which wasnt much to start with. His vital signs (pulse, respiratory rate, blood pressure, and temperature are together called that because that is exactly what they arevital) showed a blood pressure of 125/60, a heart rate of 120, a respiratory rate of 20, and a rectal temperature of 103.5. I walked a little faster.

Next page

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER ONE