Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this ebook to you for your personal use only. You may not make this ebook publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this ebook you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For A.V.W.

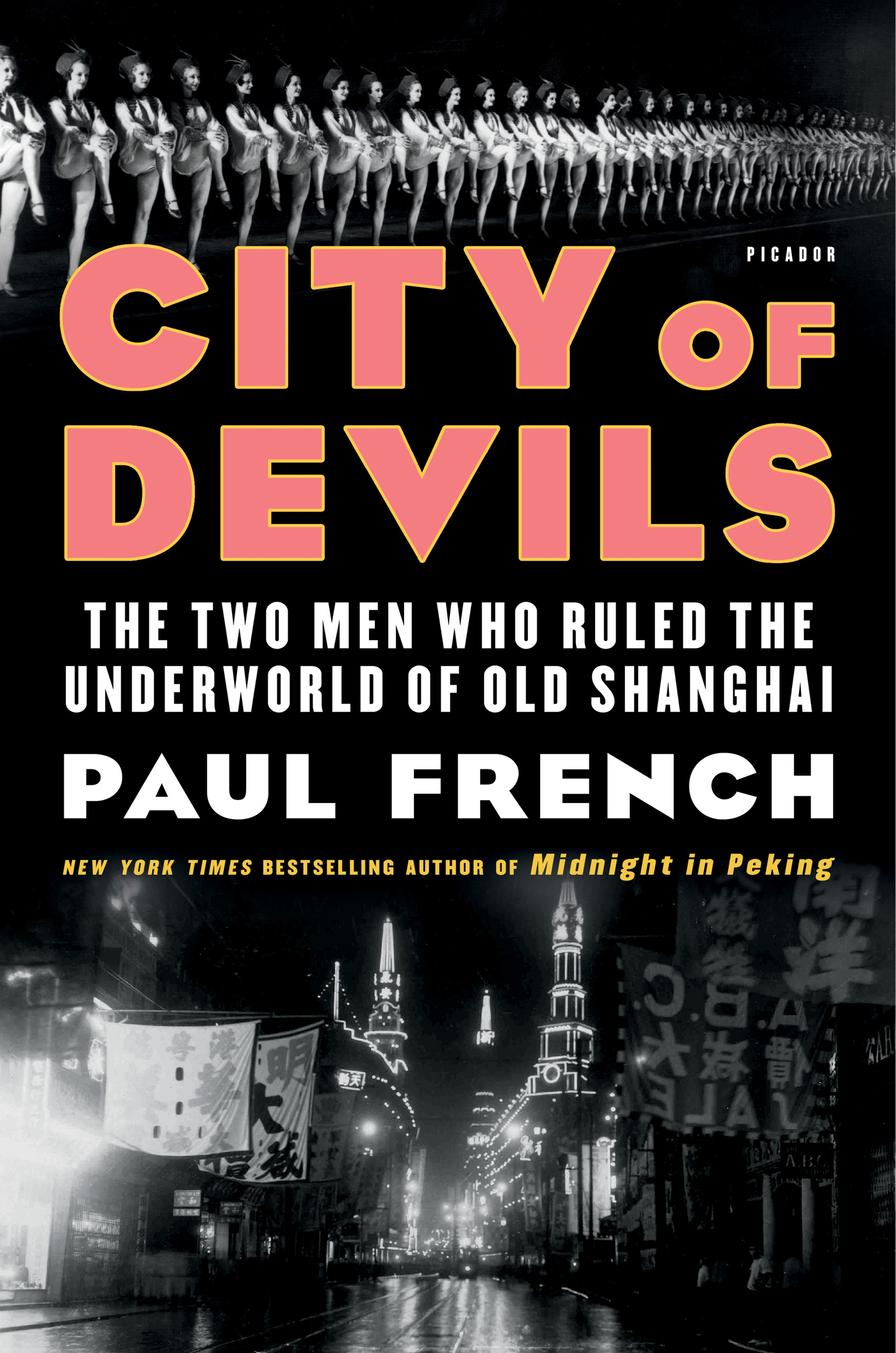

The conduct of the people was so indescribably frightful, that I felt for some time afterwards almost as if I were living in a city of devils.

Charles Dickens

Shanghai was a city of vice and violence, of opulence wildly juxtaposed to unbelievable poverty, of whirling roulette wheels and exploding shotguns and crying beggars Shanghai had become a tawdry city of refugees and rackets.

Vanya Oakes,

White Mans Folly (1943)

Shanghai. A heaven built upon a hell!

Mu Shiying,

Shanghai Fox-trot (1934)

Truly the devil pulls on all our strings.

Charles Baudelaire

I lived in Shanghai for many years. Daily I walked the citys streets, soaking up its unique atmosphere. Despite the myriad skyscrapers and overhead expressways, I spent my spare time looking for traces of what had been before, wandering a city of ghosts and trying to recapture the lives of those foreigners of so many nations who once knew the International Settlement of Shanghai as their home. In the last quarter of a century, Shanghai has become a city reborn. In the early 1950s, a virtual dust sheet was cast over the port, and little changed for more than forty years. It was only in the mid-1990s that Shanghai was allowed to thrive again. In the late twentieth and early twenty-first century I lived in a city that was building at breakneck speed, bulldozing the old and well-worn seemingly without a care, keen to construct the new and shiny as fast as possible. But an older city still, just about, exists.

Its easy to succumb to nostalgia in Shanghai. The metropolis is constantly eroding the built environment of its past. It is rapidly losing the last remnants of both its art deco and modernist architectural heritage, as well as its traditional narrow, confined rookeries and alleyways, shikumen stone dwellings and lilong lane houses. Periodically Shanghai does try to recall its previous heyday between the world wars, but every renewed bout of nostalgia becomes more disconnected, more affected by hindsight. It takes increasing amounts of imagination to catch a glimpse of the old glamour and style of Shanghai (best done at twilight or dawn, I find) down an alley, in the lobby of an old building, along the banks of one of the citys creeks and streams. In my effort to understand what the citys inhabitants once thought and why they acted as they did, my quest has always focused on the lower depths of this once remarkably cosmopolitan city, Shanghais foreign underbelly: those rarely written about, the men and women not covered in glory or fabulous riches, not feted or even remembered in the minutes and formal records of the city. Im drawn to the flotsam and jetsam, the impoverished migrs and stranded refugees, transient neer-do-wells and washed-up chancers, con men and female grifters. I seek out those foreigners who came to the China Coast and preferred to exist in the citys criminal milieu, to disappear into its laneways and backstreets. Theyre not distinguished or heroic. Invariably theyre liars and cheats. Theyre rarely anything close to good, and all are terribly flawed, often living in Shanghai because they were one step ahead of the law and, invariably, other options were few and far between. But many of them had a certain style, panache; their own particular flair. They take a lot of seeking, but their tracesfaint, sketchyremain.

City of Devils is based on real people and real events, as best as can be divined from the witnesses, participants, and reports of the time. A complete record is impossible due to the nature of the people involved, their somewhat clandestine lives, purposely hidden pasts and false names, changed birthdates and the crimes they committed and/or abetted, all of which they would never willingly confess to. Where records do exist, they are rarely as complete and as detailed as the academic historian would acceptfalsifications, clerical errors, and downright lies were exacerbated by war and devastation. Although assumptions have been made, Ive done my utmost to adhere to historical accuracy. Of course all the main players are now gone, though I am sure they would have denied everything, just as they did at the time.

This story is drawn from a wide variety of sources, primary and secondary. As we are now three quarters of a century distant from the finale of the events in this book, primary sources are difficult. Fortunately, some people who lived through those times still remain with us, while others told their stories to their children and grandchildrenthey are thanked in the acknowledgments. I trawled through a large range of secondary sources, including the archives of the Shanghai Municipal Police and the Shanghai Special Branch, the annual reports of the Shanghai Municipal Council, the archives of the British and American consulates, the records of the U.S. Court for China at Shanghai and the archives of the United States Marine Corps. I also drew upon the China Coast newspapers and periodicals of the time, especially the China Weekly Review , China Press , North-China Daily News , Shanghai Times , Shopping News , Peking and Tientsin Times and Walla-Walla (the magazine of the U.S. Fourth Marines in Shanghai). The excerpts from the Shopping News that appear in the text are genuine historical articles from the publication, with one or two minor additions in the interest of advancing the narrative.

I have tried to recreate the linguistic Tower of Babel that was the treaty port of Shanghai between the world wars. As well as English (in its British, Irish, American, and Australian variants), other commonly spoken languages were Yiddish, German, Russian, Portuguese, French, Italian, and Spanish, as well as Tagalog, Korean, and Japanese. Shanghai was also, of course, a melting pot of Chinese dialectsMandarin-Pekingese dialect and Cantonese as well as, obviously, the local Shanghainese dialect. I have used the Reverend Donald MacGillivrays A Mandarin-Romanized Dictionary of Chinese (eighth edition, 1930) to standardise the Wade-Giles system of romanisation. That said, there is no definitive answer to most of these romanisations.

Its worth noting that most slang, curses, racial epithets, and colloquial words and terms used are specific to the time and place and may, if not viewed in the context of the period and place, trouble modern sensibilities. Throughout I have sought to use those words and phrases most commonly noted in memoirs and newspapers of the time. Many are now deemed offensive, and I have no desire to revive them except in the interest of historical accuracy. Between the wars Shanghai was certainly highly cosmopolitan, but it was, in many ways both formal and informal, segregated between the Chinese and the foreigners. At times the two communities interacted and overlappedthis went for the respective criminal minority as well as the law-abiding majority of the citys populacebut, for most of the characters in this book, Shanghai was a Chinese city where they invariably worked, played, and committed criminal acts largely with other foreigners.