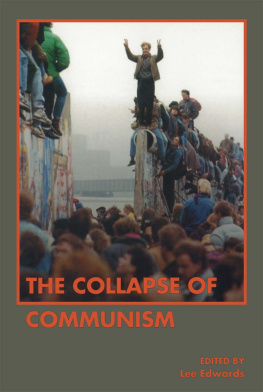

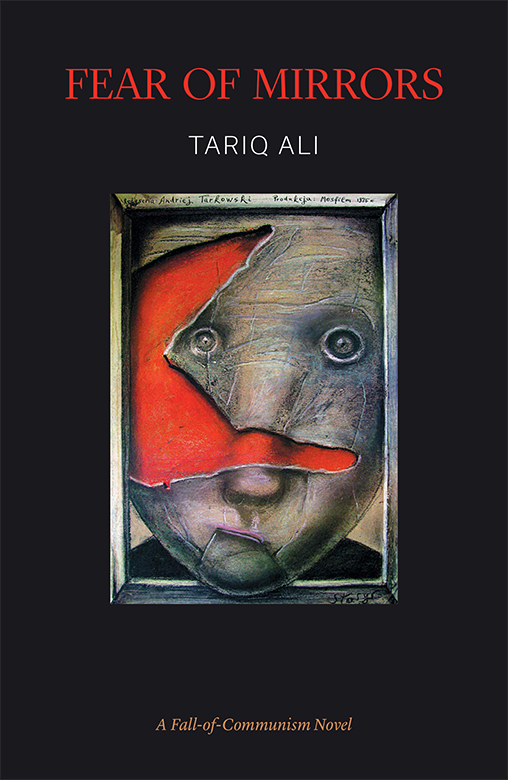

W E LIVE IN A DREARY VOID and this century is almost over. I have experienced both its passion and its chill. I have watched the sun set across the frozen tundra. I try not to begrudge my fate, but often without success. I know what youre thinking, Karl. Youre thinking that I deserve the punishment history has inflicted on me.

You believe that the epoch that is now over, an epoch of genocidal utopias, subordinated the individual to bricks and steel, to gigantic hydro-electric projects, to crazed collectivization schemas and worse. Social architecture used to dwarf the moral stature of human beings and to crush their collective spirit. Youre not far wrong, but that isnt the whole story.

At your age my parents talked endlessly of the roads that led to paradise. They were building a very special socialist highway, which would become the bridge to constructing heaven on earth. They refused to be humiliated in silence. They refused to accept the permanent insignificance of the poor. How lucky they were, my son. To dream such dreams, to dedicate their lives to fulfilling them. How crazy they seem now, not just to you or the world you represent, but to the billions who need to make a better world, but are now too frightened to dream.

Hope, unlike fear, can never be a passive emotion. It demands movement. It requires people who are active. Till now people have always dreamed of the possibility of a better life. Suddenly they have stopped. I know its only a semi-colon, not a full-stop, but it is too late to convince poor old Gerhard. He is gone forever.

These are times when, for people like me, it sometimes requires a colossal effort simply to carry on living. It was the same during the thirties. My mother once told me of how, a year before Stalins men killed him, my father had told her: In times like these its much easier to die than to live. For the first time I have understood what he meant. Life itself seems evil. The worst torture is to witness silently my own degeneration. I really had intended to start on a more cheerful note. Sorry.

Your mother and I, she in Dresden and me in Berlin, moved towards each other, seeking shelter from the suffocation that affected the majority of citizens of the German Democratic Republic. We yearned for anarchy because the centre of our bureaucratic world was based on order. Gerhard and all our other friends felt exactly the same. We loved our late-night meetings where we talked about the future full of hope and kept ourselves warm by the steam from the black coffee and the tiny glasses of slivowitz. Even in the darkest times there was always merriment. Songs. Poetry. Gerhard was a brilliant mimic and our gatherings always ended with him doing his Politburo turn.

We were desperate for liberation, so desperate that, for a time, we were blinded by the flashes emanating from the Western videosphere, which succeeded in disguising the drabness of the landscape that now confronts us.

The old order possessed, if nothing else, at least one virtue. Its very existence provoked us to think, to rebel, to bring the Wall down. If we lost our lives in the process, death struck us down like lightning. It was mercifully brief. The new uniformity is a slow killer; it encourages passivity. But enough pessimism for the moment.

This is the story of my parents, Karl. It is for you and the children that you will, I hope, father one day. Throughout your childhood you were fed daily with tales of heroism, most of which were true, but they were repetitive. And for that reason, perhaps, you will hate what you are about to read. Just like the poor used to hate potatoes.

Ever since you became a cultivated and capable young man, your mother and I have found it impossible to draw you out, to make you talk with us, to hear your complaints, your fears, your fantasies. Now I know why you couldnt say anything to us. In your eyes we had failed, and to the young failure is a terrible crime. Whatever your verdict on us, I would like you to read this till the end. At my age the passage of time appears as a waterfall, and so please treat this request as the last favour your old fart of a father is asking of you.

It has been so long since we have sat next to each other, laughed at memories of your childhood, exchanged confidences. You were still at school, your mother was still at home, the Wall still stood. I did not feel we were just father and son. I thought we were friends. Gerhard, the only one of my circle you really liked and trusted, would watch us and say: Lucky, Vlady. To have a cub like Karl.

We had our differences, of course, but I preferred to believe they were generational, even oedipal. In recent years, you have mocked my beliefs and, on one occasion, I was told you referred to me in public as a dinosaur. I was born in 1937. Not that old, is it Karl? It was your choice of epithet that surprised me.

Dinosaurs died out over a million years ago, but we are still obsessed with them. Why? Because the knowledge of how and why they became extinct has a lot to teach us about the life of our planet. There is even talk of genetically reconstructing a dinosaur. In other words, my boy, I am proud to be a dinosaur. Your analogy was more revealing than you think. Perhaps deep, deep down we are still on the same side?

My parents were revolutionaries in the golden days of communism as well as through its bloodiest years. I was a child in Moscow during a war that is now a distant memory in Europe. I have lived most of my life in the twentieth century. You were born in 1971, and with luck youll live most of your life in the twenty-first century. All you remember is the death agony of the Soviet Union, the final decadence of the state system they called communism, your mother and me working for a future that never arrived, and the re-unification of Germany.

And, of course, you remember your mother packing her case and walking out of our apartment. I know you hold me responsible for the break-up of the relationship and your mothers subsequent decision to accept the offer of a job in New York. You think it was my affair with Evelyne that was the last straw, but you are wrong. Helge and I were far too close for that to happen.

How does a marriage like ours come to an end? I think we were too similar in temperament, too like each other in too many ways. Our marriage had been an act of self-defence. She needed me to break from her orthodox Lutheran household. I needed her to get away from my mother, Gertrude. When the outside pressures disappeared, our lives suddenly seemed empty, despite the tumult on the streets. We were trapped in ourselves. Evelyne was a postscript.