CONTENTS

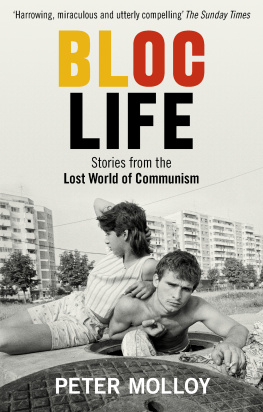

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

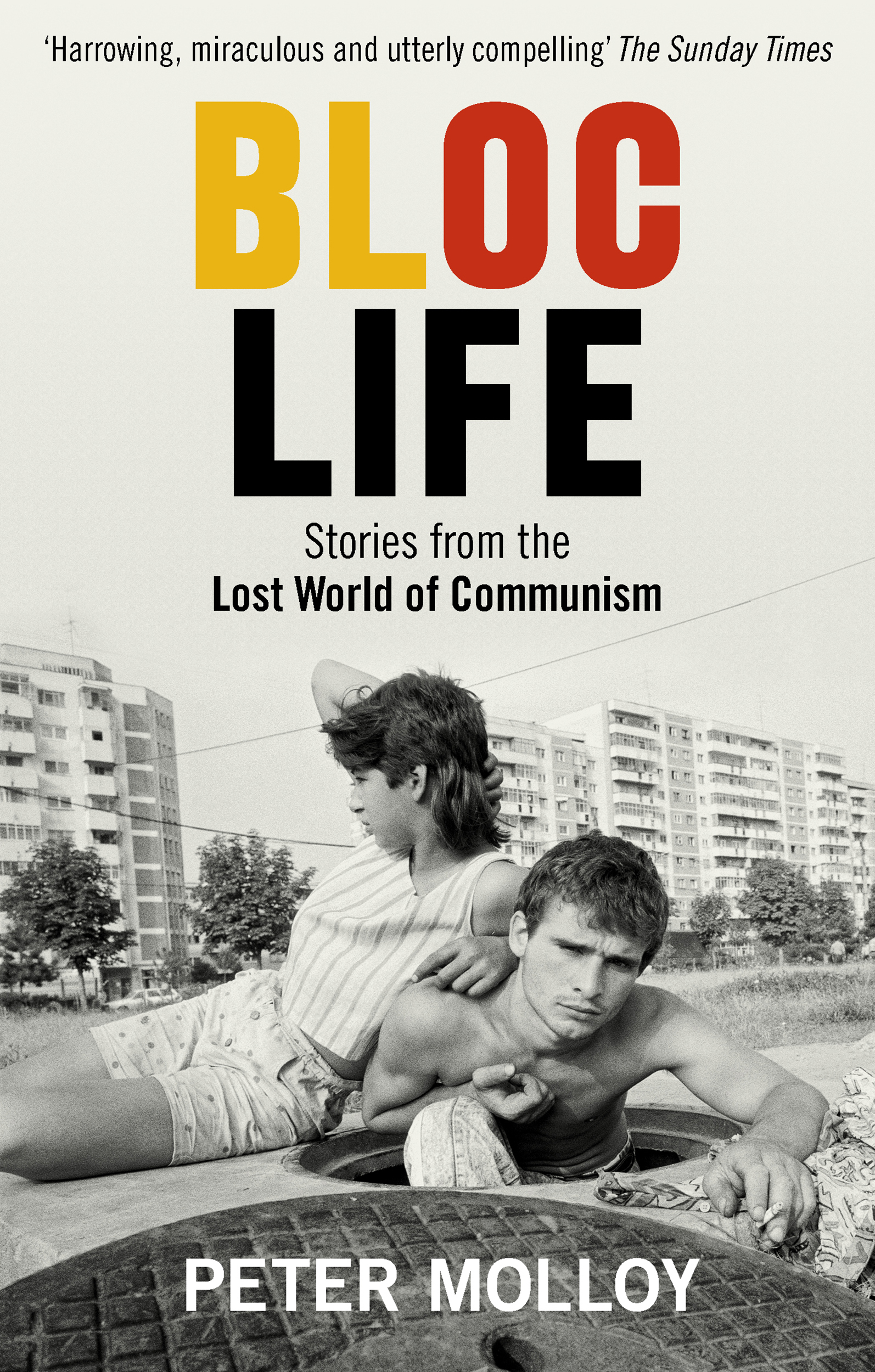

Peter Molloy is a multi-award winning producer of history and current affairs series for the BBC. He is the producer of The Lost World of Communism, on which this book is based, and his other credits include CIA, a history of Americas intelligence agency , Plague Wars, about chemical and biological warfare, Dirty Money, about international financial crime, Tobacco Wars with Michael Buerk, Suez, and Clear the Skies, about 9/11.

This book is dedicated to the memory of my late parents, Molly and Jack

INTRODUCTION

A spectre is haunting Europe the spectre of Communism.

First line of the Communist Manifesto (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels

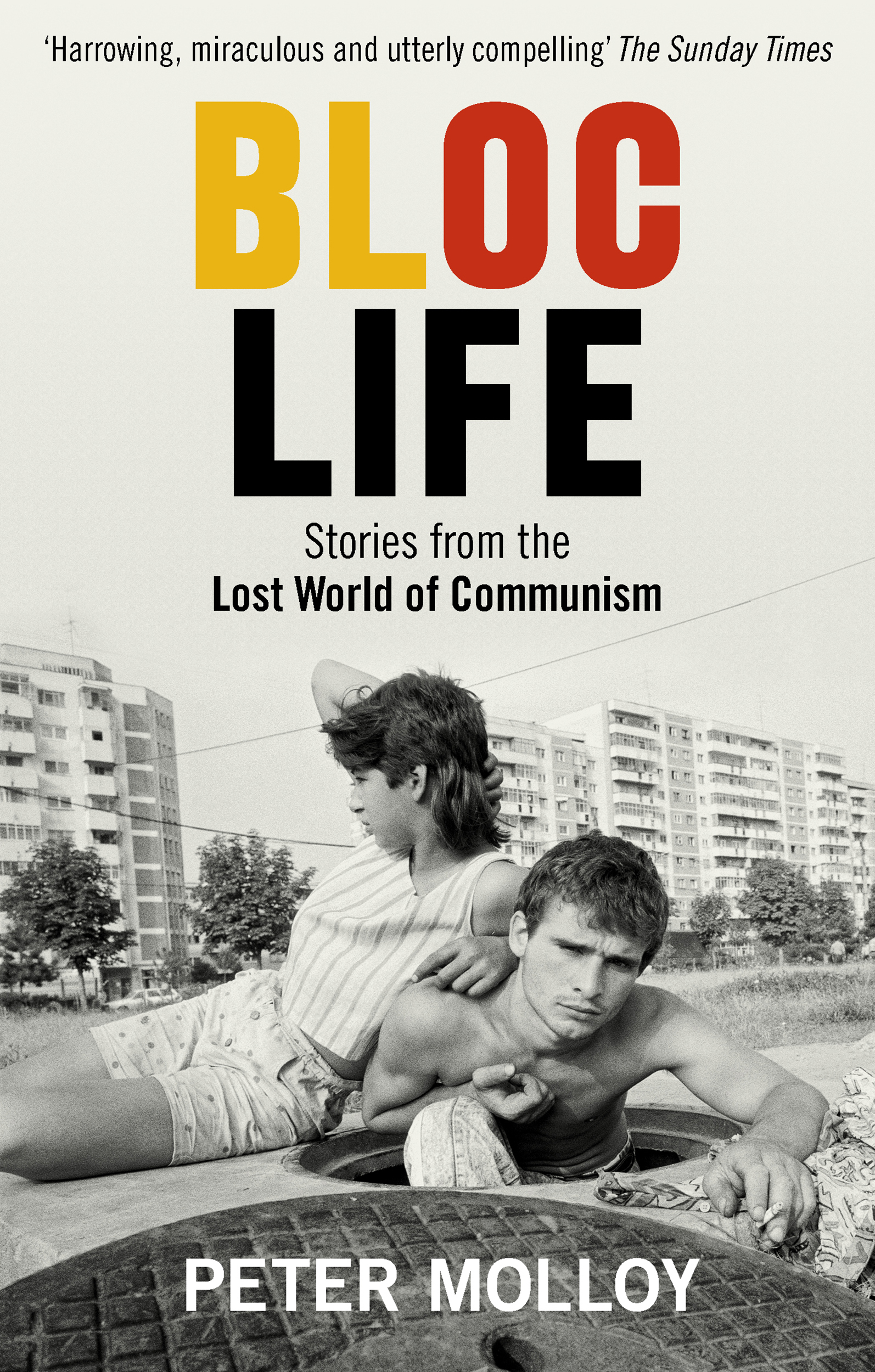

In 1989 a way of life ended for millions of people behind the Iron Curtain. The Berlin Wall came down, communism collapsed in Eastern Europe and the Cold War ended. It was a year of revolution to rank alongside 1789 or 1917.

But what was life really like for East Europeans, effectively imprisoned in the Eastern bloc? The headlines of Cold War spies and secret police surveillance, of political repression and dissident activism do not tell the whole story. After the end of the Cold War, some remembered their lives as perfectly ordinary, others hankered for the security and certainty of life under communism while still more missed the camaraderie or the privileges attendant on power.

This book gathers unique personal testimony from those who lived in communist East Germany, Czechoslovakia and Romania. Their recollections evoke the moods, preoccupations and experiences of a lost world of communism. The three societies were very different, experiencing very different kinds of rule.

In East Germany people lived under the collective leadership of a one-party dictatorship. In Romania they experienced life under a one-family dictatorship during the rule of Nicolae and Elena Ceauescu. In Czechoslovakia, where the Communist Party tried to break away from its Stalinist past, they briefly experienced a more democratic form of communist rule. The failure of those reforms following invasion on 21 August 1968 consigned Czechoslovaks to two further decades of dictatorship and stagnation known as the era of forgetting.

During the Second World War, the worlds first communist state, the Soviet Union, had borne the brunt of Nazi aggression with over 27 million dead. It is unsurprising that as victory approached its leader, Josif Vissarionovich Stalin, was determined to secure his countrys western boundaries. To many on the left, despite his arbitrary reign of terror Marshal Stalin remained an iconic figure associated with liberation from Nazi tyranny.

Communist rule in Eastern Europe rolled in behind waves of Soviet tanks as the Red Army liberated countries soon termed the Eastern bloc. Largely speaking, these were Czechoslovakia, Romania, Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria and, initially, Albania. Militarily, they ultimately all joined the Warsaw Pact, designed to defend international socialism against capitalist powers. Yugoslavia under Marshal Josip Tito, although a socialist country, broke away from the USSR in 1948.

Following conferences at Yalta and Potsdam between the Soviet Union and the Western allies in 1945 Europe had been effectively divided into two spheres of influence. Occupied Germany was divided into four zones and Berlin was separated into four sectors. The scene was set for the Cold War.

It was, in essence, an ideological conflict between a capitalist West and a communist East that included the Soviet Union and the countries of Eastern Europe. Winston Churchill presciently observed the new European political landscape in a speech delivered in America in March 1946. From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the Continent. Behind that line lie all the capitals of the ancient states of Central and Eastern Europe. Warsaw, Berlin, Prague, Vienna, Budapest, Belgrade, Bucharest and Sofia, all these famous cities and the populations around them lie in what I must call the Soviet sphere, and all are subject in one form or another, not only to Soviet influence but to a very high and, in many cases, increasing measure of control from Moscow The Communist parties, which were very small in all these Eastern States of Europe, have been raised to pre-eminence and power far beyond their numbers and are seeking everywhere to obtain totalitarian control Whatever conclusions may be drawn from these facts and facts they are this is certainly not the liberated Europe we fought to build up.

Support for communism and the Soviet Union varied greatly between nations. In Czechoslovakia communism was already a significant political force prior to the arrival of the Red Army. Historically, the Czechs and the Slovaks looked upon the Soviet Union as a friend. A successful Soviet-backed Communist Party existed in prewar Czechoslovakia. In 1938, the Soviet Union was the only power to declare iself ready to aid Czechoslovakia. When Soviet troops entered Prague in May 1945, they were welcomed as liberators. In the free elections of 1946, the Communist Party won 38 per cent of the vote. It was the largest showing of support for communism ever expressed in Eastern Europe in a democratic ballot. The communists were the largest party in parliament and had a key role in a coalition government.

The Czech writer Pavel Kohout, although from a bourgeois background, was an ardent young communist at the end of the Second World War. The reasons for his conversion to communism echo those of many Czechoslovaks of the time. He was disillusioned with capitalism, dismayed with Britain and Frances abandonment of their country to Hitlers mercies in the Munich Agreement of September 1938 and supported the Soviets in 1945. My father found no protection in his bourgeois origin nor in his knowledge of seven languages against a four-year period of unemployment, so my first significant life experience was the world economic crisis, which in this country was perceived as a total failure of capitalism. We wanted to prevent Czechoslovakia, which ranked among the ten most advanced countries, from going through the same crisis it had experienced in the 1930s.

The second reason, which I felt even more strongly about, was the Munich Treaty. It was seen in Czechoslovakia as a total failure of the Western democracies. The English and French left us out on a limb in 1938 when Neville Chamberlain came home with the famous statement about peace with honour. And when the country was liberated by the Red Army, the seeds were sown for the majority of inhabitants to change the system and the protector.

Communism was about sharing a revolutionary vision of a more just world. Industrialization and collectivization would transform the economy. A new type of socialist personality with a collective sense of values would transform society. The guiding principle would be, from each according to his ability, to each according to his need.

What Eastern Europeans actually experienced in those post-war years, however, had little to do with such a utopian vision and everything to do with an extraordinary level of social and political control, modelled on Stalins Soviet Union.

Next page