Leo Lionni - Parallel Botany

Here you can read online Leo Lionni - Parallel Botany full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1978, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Parallel Botany

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:1978

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Parallel Botany: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Parallel Botany" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Leo Lionni: author's other books

Who wrote Parallel Botany? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Parallel Botany — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Parallel Botany" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Leo Lionni

Parallel Botany

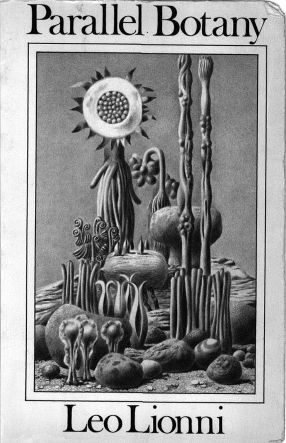

PARALLEL BOTANY

|

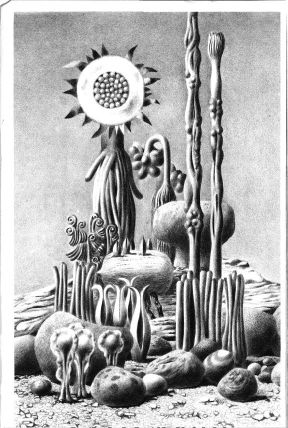

PL . I A garden of parallel plants

LEO LIONNI

PARALLEL BOTANY

Translated by PATRICK CREAGH

Copyright 1977 by Leo Lionni

All rights reserved under International

and Pan-American Copyright Conventions.

Published in the United States

by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York,

and simultaneously in Canada

by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Distributed by Random House, Inc., New York.

Grateful acknowledgment is made

to Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc.,

for permission to reprint one line from

" Poetry" from Collected Poems of Marianne Moore.

Copyright 1935 by Marianne Moore,

renewed 1963 by Marianne Moore and T. S. Eliot.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Lionni, Leo [date]

Parallel botany.

Translation of La botanica parallela.

i. Botany -Anecdotes, facetiae, satin, etc. I. Title.

PQ5984.L55B6I3 sSi'.oao? 77-74985

isbn 0-394-41055-6 0-394-73302^-9 (pbk.)

Photographs are by Enzo Ragazzini

Manufactured in the United States of America

First American Edition

Imaginary gardens with real toads in them.

MARIANNE MOORE

PART ONE: INTRODUCTION 1

General Introduction 3

Origins 20

Morphology 35

PART TWO: THE PLANTS 57

The Tirillus 59

Tirillus oniricus 62

Tirillus mimeticus 64

Tirillus parasiticus 67

Tirillus odoratus 68

Tirillus silvador 70

The Woodland Tweezers 73

The Tubolara 78

The Camporana 80

The Protorbis 86

The Labirintiana 95

The Artisia 100

The Germinants 112

The Stranglers 117

The Giraluna 119

Giraluna gigas 134

Giraluna minor 1 43

The Solea 145

The Sigurya 162

PART THREE: EPILOGUE 171

The Gift of Thaumas 173

Notes 178

PLATES

i A garden of parallel plants

ii Leaves of Antola enigmatica

iii Woodland tweezers at the base of a ben tree

iv Algal Lepelara

v Lepelara terrestris

vi Fossil Lepelara from Tiefenau

vii Fossils of the bulbous tiril

viii Kumode plants

ix Anaclea taludensis

x Tirils

xi Propitiatory leaf-boat of the Okono Indians

xii Parasitic tirils

xiii Woodland tweezers

xiv Tubolara

xv Camporana

xvi Camporana menorea

xvii Protorbis

xviii The Katachek Protorbis

xix Leaf of Labirintiana labirintiana

xx Artisia

xxi Kaori tattoos

xxii The Cadriano germinanis

xxiii Strangler tirils

xxiv Giraluna (closeup of avvulta at right)

xxv The ebluk procession (Sumerian bas-relief)

xxvi Wo'swa, the bride of Pwa'ko

xxvii Giraluna minor in typical habitat

xxviii Casts of Solea

xxix Tips of Solea

xxx The great Stone of Ta

xxxi Sigurya barbulata

xxxii Sigurya natans

In ancient times botany was part of a single science that included everything from medicine to the various skills of agriculture, and it was practiced by philosophers and barbers alike. At the famous medical school of Cos (fifth century b.c.) Hippocrates, and later Aristotle, laid the foundations of the scientific method. But it was Theocrastus, a pupil of Aristotle, who first worked out a rudimentary system for observing the vegetable world. The influence of his Historia Plaitarum and De Plantarum Causis was passed on to later ages by Dioscorides, and is to be found lurking everywhere in the medieval herbaria composed by the scrivener monks in their cloistered gardens, with their humble little plants, each on its minute altar of earti, as still and perfect as waiting saints, wrapped in a solitude that defies time and the passing seasons.

After Gutenberg, plants also came to have a new iconography. Instead of the delicate washes applied with loving patience, and expressing the very essence of the petals and leaves, we now have the coarseness of woodcuts and the flat banality of printer's inks.

In 1560 Hieronymus Bock published a volume, illustrated with woodcuts, in which he described 567 of the 6,000 species of plant then known in the Western world, including, for the first time, tubers and mushrooms. "These," he wrote, "are not grasses, or roots, or flowers, or seeds, but simply the excess of humidity that is in the soil, in trees, in rotten wood and other putrescent things. It is from this dampness that all tubers and mushrooms spring. This we can tell from the fact that all mushrooms (and especially those used in our kitchens) most commonly grow when the weather is wet or stormy. The Ancients were in their time particularly struck by this and thought that tubers, not being born from seed, must in some way be connected with the sky. Porphyry himself expresses as much when he writes, 'Mushrooms and tubers are called the creatures of the Gods because they do not grow from seed like other living things.'"

Less than a century after the invention of printing, the conquistadores and the captains of the East India companies showered an astounded Europe with a perfumed cornucopia from the gardens and jungles which had until then slept beyond the oceans. Hastily, thousands of new plants had to be named and placed within a rudimentary and inefficient system of classification.

It was not until the first half of the eighteenth century that the Swedish botanist Linnaeus created a system of botanical classification that seemed to be definitive, a botanical register where all the plants of the earth, present and future, could be given a name, a degree, and a brief description. Linnaeus published his Systema Naturae and in 1753 introduced the double nomenclature giving each plant two Latin names, one for the genus and the other for the species. By now no fewer than 300,000 plant names compose one enormous random poem that records, commemorates, describes, exalts, and celebrates all that man has discovered of the world of plants.

All seemed ready for the emergence of the new science. Freed from their obsession with classification, botanists began to ask themselves how and why plants behave as they do. Chemistry, physics, and genetics provided new instruments of research, while classification gave way to etiology, the study of origins. Botany, called upon to establish a logical and causal relationship between the morphological structure and the vital functions of plants by experimental methods, became a modern science.

The future seemed securely mapped out: from the small to the smaller still, and so ad infinitum. It was thought that at that point, paradoxically enough, would occur the sudden fusion of knowledge that would explain everything in the universe.

But the triumphant and comforting prospect of a research program gradually but inevitably unraveling itself over the centuries was destined to be severely jolted by the news of the discovery of the first parallel plants, of an unknown vegetal kingdom which, being by nature arbitrary and unforesesable, appeared-and still appears to challenge not only the most recently acquired biological knowledge but also the traditional structures of logic.

" These organisms," writes Franco Russoli, "whose physical being is sometimes flabby and sometimes porous, at other times osseous but fragile, breaking open to display huge colonies of seeds or bulbs which grow and ferment in the blind hope of some vital metamorphosis, that seem to struggle against a soft but impenetrable skin- these abnormal creatures with pointed or horny protuberances, or petticoats, skirts and fringes of fibrils and pistils, articulations that are sometimes mucous and sometimes cartilaginous, might well belong to one of the great families of jungle flora, ambiguous, savage, and fascinating in their monstrous way. But they do not belong to any species in nature, nor would the most expert grafting ever succeed in bringing them into existence."1

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Parallel Botany»

Look at similar books to Parallel Botany. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Parallel Botany and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.