ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

All reasonable efforts have been made to locate copyright holders. Where they have held the copyright, the directors and/or governing bodies of the institutions listed in the bibliography have kindly given permission to cite and to quote from original sources.

I have specifically to thank: The Direco-Geral de Arquivos, Lisboa; the Curator, Early Modern and Osborn Collections, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University; the Keeper of Special Collections, Bodleian Library, University of Oxford; the Trustees of the British Library, London; the UK Science and Technology Facilities Council and the Syndics of Cambridge University Library; the Director, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan; the Director, National Library of Australia; the Archive and Manuscripts Manager, National Maritime Museum, London; the Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London; the Director, Perkins Library, Duke University; the Keeper of the Public Records, Public Records Office, National Archives, Kew; the Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; the Librarian and Director of the John Rylands University Library, University of Manchester; the State Librarian and Chief Executive, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney; the Director of the Sutro Library, the San Francisco branch of the California State Library; the National Librarian, National Library of New Zealand: Te Puna Mtauranga o Aotearoa, Wellington.

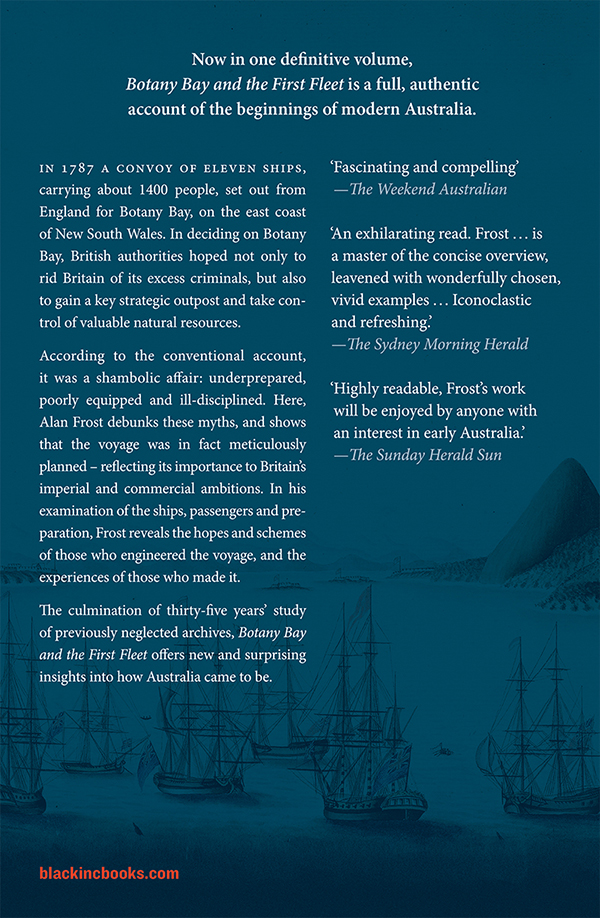

Some sections of this work were first published (in somewhat different form) in Convicts and Empire: A Naval Question, 17761811 (Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1980), Arthur Phillip, 17381814: His Voyaging (Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1987) and Botany Bay Mirages: Illusions of Australias Convict Beginnings (Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1994). The publishers have kindly agreed to my including them here.

*

During a long career and mine now comprehends fifty years an academic writer learns from many people and accumulates many debts, some obvious, but others obscure. It would be an impossibility for me now to list all of those friends and opponents (in an intellectual sense) to whom I am indebted for numbers of the insights I offer here. However, there are some people whom I do wish to thank explicitly.

Geoffrey Blainey has steadily encouraged me to develop my views, and I also benefited from discussing them with Geoffrey Bolton. Extended conversations with Bernard Bailyn have enabled me the better to place the Botany Bay decision in the context of the Atlantic world of the 1780s. Isabel Moutinho has helped me to uncover the Portuguese dimension of British thinking about what to do with the convicts. Michelle Novacco facilitated research in England. I have had significant help from Gary Sturgess, who also possesses very extensive knowledge of the documentary record, and who has freely shared his knowledge, both by extended conversations about meanings and significance, and by locating and providing materials I did not know about. Briony Sturgess has also helped in this last task. Advice from Gary Sturgess and Michael Flynn has enabled me to correct some mistakes in the first printing.

The generous encouragement and hospitality that Glyndwr Williams and Sarah Palmer have offered over many years have made my periods of research in England so much more pleasurable than they otherwise would have been. I am grateful, too, for the extended friendship and encouragement of John Salmond, Inga Clendinnen and Roger Wales, now sadly all gone into the world of light.

Natasha Weir undertook the bulk of the laborious task of transcribing and editing the c. 2500 drafts, original papers and letters and copies on which these studies are based. This electronic database is now available at the State Library of New South Wales.

I have also warmly to thank the editorial and production staff at Black Inc., in particular Chris Feik, Denise ODea and Lauren Carta.

*

I have been in the curious situation of being a historian of Australia who has had to travel repeatedly to overseas archives to study the circumstances of our beginnings. These research trips would have been impossible without financial support from La Trobe University and the Australian Research Council, and the writing up of results would have been even more protracted without periods of leave from teaching given by La Trobe University. I thank both organisations warmly.

Even in being grateful for the substantial help I have had, however, I must also express my deep regret about how the university world has changed in recent decades. It would now be virtually impossible to commence a research project such as this, which has taken thirty-five years to complete. Universities and external funding bodies would require results within two to three years; and the concomitant regimens of grant applications and reporting requirements would mean that you would have to present your findings without the benefit of the leisure to reflect on them and on what you might still look for. And without efficient performance, you would find it progressively more difficult to obtain the further research grants you would need to complete the project. Universities and scholarly pursuits more generally are not businesses or government departments, and they shouldnt be regulated as though they are. In measure as they are, so is our intellectual life diminished.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

R.G. Albion, Forests and Sea Power: The Timber Problem of the Royal Navy, 16521862 (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1926).

Alan Atkinson, The Europeans in Australia, 1: The Beginnings (Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1997).

Bernard Bailyn, Atlantic History: Concept and Contours (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., 2005).

George Barrington, The History of New South Wales (London, 1802).

G.B. Barton, History of New South Wales from the Records, 2 vols (Charles Potter, Government Printer, Sydney, 188994).

Charles Bateson, The Convict Ships, 17871868, 2nd ed. (A.H. and A.W. Reed, Sydney, 1974 [1969]).

Daniel Baugh, British Naval Administration in the Age of Walpole (Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 1965).

J.M. Beattie, Crime and the Courts in England, 16601800 (Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 1986).

Geoffrey Blainey, The Tyranny of Distance: How Distance Shaped Australias History (Sun Books, Melbourne, 1966).

Geoffrey Blainey, A Reply: I came, I Shaw , Historical Studies, vol. 13 (1968), pp. 2046.

Geoffrey Blainey, Botany Bay or Gotham City?, Australian Economic History Review, vol. 8 (1968), pp. 15463.

David Blair, The History of Australasia (McCreedy, Thompson and Niven, Glasgow, Melbourne and Dunedin, 1878).

G.C. Bolton, The Hollow Conqueror: Flax and the Foundation of Australia, Australian Economic History Review, vol. 8 (1968), pp. 316.

G.C. Bolton, Broken Reeds and Smoking Flax, Australian Economic History Review, vol. 9 (1969), pp. 6470.

John Brewer, The Sinews of Power: War, Money and the English State, 16881783 (Unwin Hyman, London, 1989).

Asa Briggs, The Making of Modern England, 17831867: The Age of Improvement (Harper and Row, New York, 1965 [1959]).

W.S. Campbell, Arthur Phillip, JRAHS, vol. 21 (1935), pp. 2646.

A.K. Cavanagh, The Return of the First Fleet Ships, The Great Circle, vol. 11, no. 2 (1989), pp. 116.

J.D. Chambers and G.E. Mingay, The Agricultural Revolution, 17501880 (Batsford, London, 1966).

Emma Christopher, A Merciless Place: The Lost Story of Britains Convict Disaster in Africa and How it Led to the Settlement of Australia

Next page