All Rights Reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers.

It might perhaps be practicable to direct the strict employment of a limited number of convicted felons in each of the dock-yards, in the stanneries, saltworks, mines and public buildings of the kingdom.

The more enormous offenders might be sent to Tunis, Algiers, and other Mahometan ports, for the redemption of Christian slaves.

Others might be compelled to dangerous expeditions; or be sent to establish new colonies, factories, and settlements on the coasts of Africa, and on small islands for the benefit of navigation.

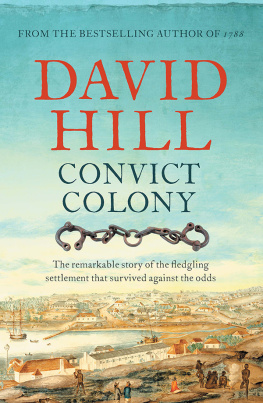

Preface

In 1975, shifting the focus of my scholarly interest from English literature to history, I began to research the reasons for the British colonization of New South Wales in 1788.

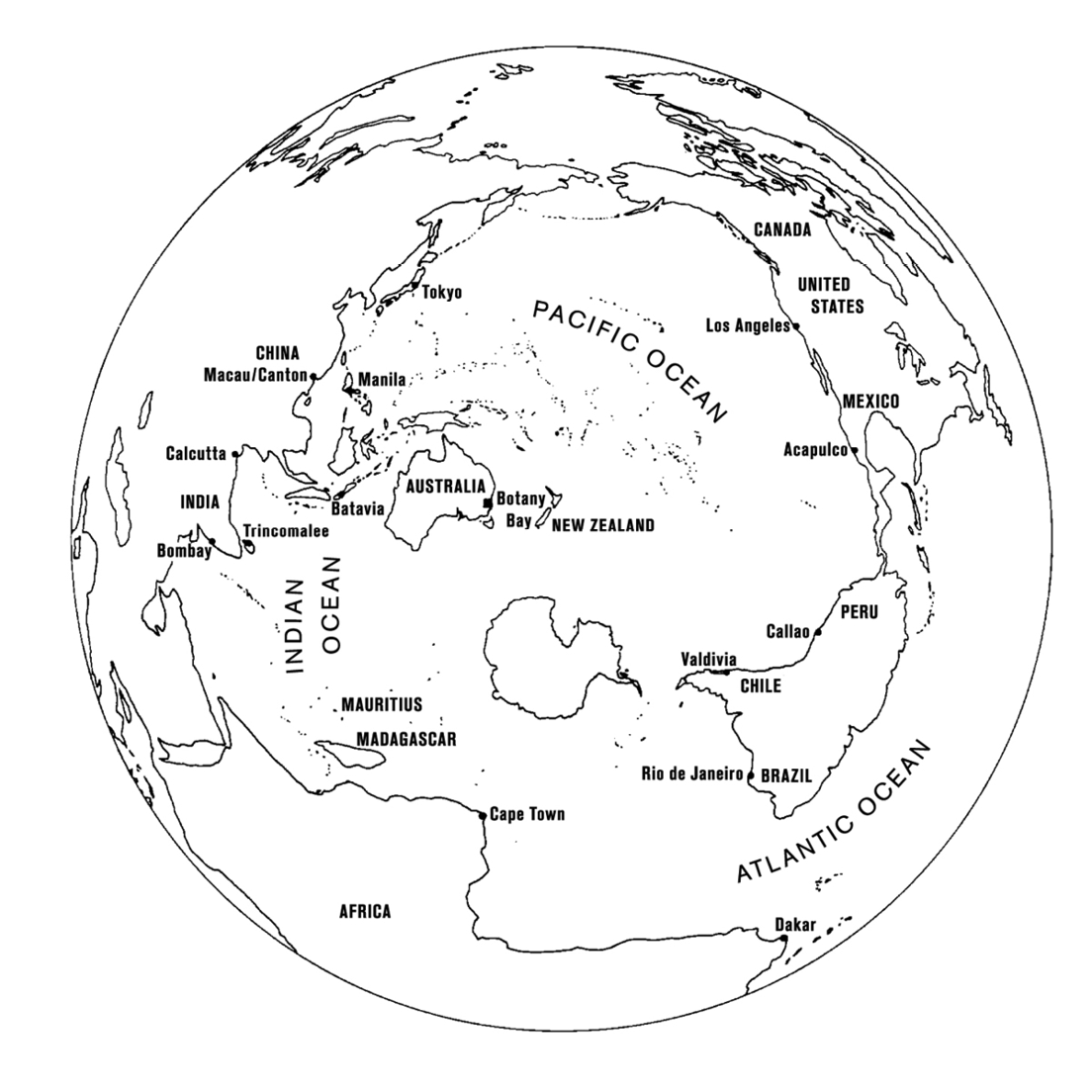

Then, I had no real idea for how many years this quest would occupy me, and how arduous it would prove. In the 1980s and 1990s, I published a number of substantial studies which bore, to a greater or lesser extent, on the general question: Convicts and Empire (1980); Arthur Phillip, 17381814: His Voyaging (1987); Sir Joseph Banks and the Transfer of Plants to and from the South Pacific, 17861798 (1993); Botany Bay Mirages (1994). Even so, I still had only a limited sense of the magnitude of the task, whose horizons kept expanding witness The Global Reach of Empire (2003).

The one thing above all others that I did not know when I commenced this research was the full extent of the documentary base awaiting discovery. When I began, I naturally attended to those sources which had either been published (as in Historical Records of New South Wales (1892)) or cited in what were then the standard histories of the beginning of modern Australia (by Ernest Scott, Sir Keith Hancock, Sir Max Crawford, Manning Clark and A.G.L. Shaw). But as I investigated further, and in particular as I came to know better the administrative practices of British government departments in the last decades of the eighteenth century, I uncovered more and more relevant documents.

The essays in Botany Bay Mirages were based on some 600 documents, and in the Introduction to that work I optimistically forecast that there might be perhaps 200 more to be collected. Even so, I still had no proper idea of the actual extent of the records. I kept searching, and kept finding more documents. When in 2003 I applied for a large ARC grant to continue the process, I thought that I should probably end up with 1000. I received the grant and went back repeatedly to the Public Record Office, now the National Archives, in London. I found more and more documents so many that at times it seemed as though there would be no end to the business. I would utter low groans each time I opened a new file to find yet another dozen or fifty that needed to be recorded.

In the end, I gathered 2500 documents (including copies). To be sure, there is often much repetition in these as, according to the practice of the times, writers summarized or repeated at length the contents of the letters they were minuting or answering. But taken together, and when combined with other sources which also reflect government deliberations (such as secondary correspondence and newspaper reports), this base constitutes a matchless record of that moment in times long travail that led to the emergence of Australia. (These documents are to be made available on a dedicated website at the State Library of New South Wales. It is my hope that this will become an enduring record for the future, as new documents are added to it and as other historians make use of it for different purposes.)

The greatly enlarged documentary record means that we are now in a position to understand better than ever before why the British decided to colonize New South Wales. In this volume and its forthcoming companion, The First Fleet: The Real Story, I analyze this decision and how it was implemented.

As has been true generally of my past writing about British imperialism in the second half of the eighteenth century, what I am most concerned with in these studies are the political and strategic decision-making processes, and the administrative procedures by which decisions were implemented. Some of what I say here I have said before, but not in such an extensive or focused way. Also, a number of my conclusions now differ markedly from some I offered thirty years ago. I understand more now than I did then.

Much of what I say, I know, contradicts what has become received wisdom in Australian history. To some readers, it may seem the height of folly or arrogance to gainsay what the renowned historians of Australian colonization have said; and to do so, moreover, in polemical fashion. But this is what I am doing in these studies I am challenging the established historiography of Australias beginnings, which I believe to be both severely limited in its perspective and wrong in a number of its central conclusions.

In disagreeing with my colleagues and predecessors, I mean no personal disrespect. However, there is no gentle way of arguing against a whole tradition of historiography. If I intend to call it into fundamental question, then it is best that I do so directly and honestly. Only in this way is the cause of history properly served; and also that of the nation, in that we shall come to a better understanding of whence we came, and therefore who we are.

Editorial Practices

The documents I have located, and from which I quote here, have been transcribed and edited by Dr Natasha Campo and myself. Mostly, we have modernized spelling, capitalization and punctuation. (The principal exception is that we have left in their original form legal documents, such as Letters Patent and Acts of Parliament.) Sometimes, in the interest of readier comprehension, we have also broken up very long passages into shorter paragraphs (including in Letters Patent). While misspellings have been silently corrected, we have indicated where we have corrected obviously wrong words. We have standardized the spelling of personal and geographical names. However, I have retained older spellings when to alter them would lead to confusion (e.g., Bombay rather than Mumbai, as no eighteenth-century European source gives the modern Indian term).

Introduction

Between 1718 and 1775, British authorities transported some 50,000 male and female criminals across the Atlantic Ocean to the North American colonies (most to Virginia and Maryland), where their labour was sold to merchants and planters for terms not longer than seven years.