To Joe Largo.

Thank you for your help and for being a son who makes a father proud.

What is a weed?

A plant whose virtues have never been discovered.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

CONTENTS

What is green and allows you to breathe? That life-sustaining lungful of air you just took had to come from somewhere. Without plants, and the oxygen they produce, there could be no animal life on earth. These were our planets pioneering organisms, who first learned the tricks of adaptation to survive on our once-sterile rock, and who turned it into the vibrant, blue-green home we know today. They are both our forerunners and our contemporaries in lifebut what do we really know about plants?

No one has cracked the encrypted language of plants. Insects chirp, bees buzz, animals growl, hiss, hum, and even transmit low-frequency sound waves. But plants, as far as we know, never say a thing. Fields of tall summer grasses waft without agency, moving whichever way the wind blows. Roots stay where their seeds originally sprouted. A rose makes no announcement when its bud opens in full-petal bloom. Pine trees in a forest stand like silent sentries. A bent coconut palm owes its haphazard arc to the ocean winds and sea mist; it is silent on the changes its species needed to learn in order to survive where it does. There are trees living today that are estimated to be eight thousand years old, and nearly microscopic phytoplankton that live and die within an hourbut neither will divulge their history or the secrets they contain unless we look. Without plants, we would simply not be here.

Plants have no brains. We can be certain they have absolutely no way to perceive this world in any way remotely similar to our view. But is there another level of consciousness we have yet to understand? Plants do everything possible to survive and to reproduce toward the continuation of their species. This is no easy feat, particularly as disadvantaged as plants are to alter the environment in which they find themselves. The seemingly magical biochemistry these entirely stationary organisms acquired to survive and thrive is astonishing. Much has come from looking at the chemistry within; for example, we now understand how a plant produces oxygen via photosynthesisan amazing process we would never be able to duplicateand there are countless other techniques plants employ that even the smartest computer could not match.

The primary goal of every living organism is individual survival and the preservation of its species. As more complex plants arose, new ways to procreate came into play. Plants had to find a way to attract helpers to transfer male pollen to a female ovary in order to make a babywhat botanically we call fruits, or seeds. The collection of means they devised to accomplish this all-important process was and still is diverse. What we admire as a flower is basically a billboard, grown with the sole purpose of saying Hey, check me out to bees, beetles, or birds. Some enticed with sweet nectar, others chose toxins and traps, yet all methods proved to be marvelously diverse and interesting.

Most of what our earliest ancestors knew of plants has been forgotten. The first attempt to catalog plants is found in sacred Indian texts from 1100 B.C., known as the Avestan Writings. Aristotles student Theophrastus compiled a book, Historia Plantarum, sometime during the second and third century B.C. that included information on 500 different species. The most important book about plants was written by first-century A.D. Greek physician Pedanius Dioscorides, titled (when later translated into Latin) De Materia Medica, which remained the standard and most extensive book about plants for nearly sixteen centuries. These books treated botany more like herbalism, and were meant to reveal the best plants for medical purposes. There was no science, no medicine, no pharmacology for early peoples; the kinds of things we depend on from science were found in plants, and survival depended upon knowing the properties and secrets each species held.

In this book, I try to combine the reference-like quality of these early texts and the most fascinating folklore of the past, with descriptions, life cycles, advice on cultivation, and the benefits these plants provide. But more important, I hope to capture the incredible diversity of plants and marvel at the vast plant kingdoms many wonders. We need to look at the amazing greenness about us in a new waywith not only awe and respect, but also renewed curiosity. Likewise, we must protect the incredible flora we are fortunate to still have among us, lest our own actions cause them to disappear forever.

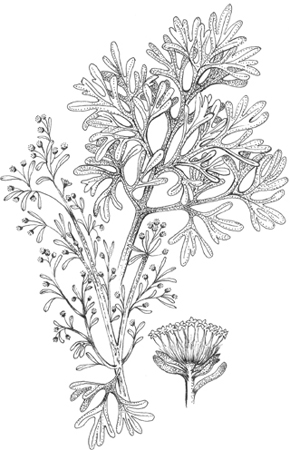

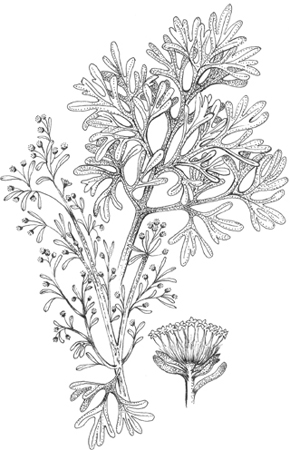

ABSINTHE

Artemisia absinthium

Green Madness

Along ancient dirt roads and on the hillsides of England, in most of Europe, the Middle East, and in fact all the way to the edge of Asia, a brilliantly green, pointed-leaf plant once grew in abundance. It flourished in bushy clusters, reaching about three feet in height with a thin, nonwoody stem. From early summer until the last days of autumn, its yellow, button-size flowers bloomed up and down its stalks like miniature strobe lights, creating an inviting, colorful landscape.

Absinthe, commonly called wormwood, is a perennial plant. Like other perennials, absinthe loses its flowers, leaves, and stems each winter, withering to nothing. However, its sturdy, fibrous roots remain dormant in the soil, springing to life each year when the snow and cold weather cease. It grows rapidly, and because it relies on the simplest method of seed disbursementallowing gravity to simply spread its seeds around the base of the parent plantwormwood once dominated landscapes for miles. Due to its speedy germination and quick growth, it killed (often smothering with its shade) all other plants that attempted to occupy its ground.

A common practice in early civilizations was to field-test every plant people found, including absinthe, in order to discover what use it might have in aiding survival. Absinthe, despite its vast availability, was thought to be rubbish, particularly after it was deemed inedible. Extremely bitter in both taste and odor, wormwood became such a widely recognized synonym for something nasty, unpleasant, and even poisonous that the Bible refers to it that way more than a dozen times. For example, in the book of Revelation: A third of the waters became wormwood, and many people died from the water.

Still, despite its reputation, people did eventually find uses for absinthe. The ancient Greeks named the plant apsinthos, sometimes referring to it as Artemisia after the goddess of medicine, Artemis. They believed the plant could be used in an elixir to kill intestinal worms. In medieval times, doctors and alchemists recommended it as a last-ditch cure for tapeworms and other stomach alimentsalthough it was likely to poison the patient as wella practice that would lead to the nickname wormwood. Looking to the plants around them almost as we would a vast supermarket or drugstore, early civilizations believed every plant was put on earth with a purpose, that often being to help humankind. Wormwoods sap found use as a salve to repel fleas and ticks, and the ancient Egyptians even used it as an additive to certain wines as early as 1500 B.C.

Absinthes real heyday would eventually derive from our unceasing desire to find new intoxicants. Historians have even argued that human beings moved from a nomadic species to one that stayed putultimately creating cities and civilizationsprimarily out of a desire to guard and nurture the plants that made wine and other inebriating tonics or ale. In the mid-1600s, after naturalist Nicholas Culpeper included a recipe for a drink made from wormwood in his book