T he events of the early hours of Friday 12 October 1984 will remain sharply remembered by those who lived through them, or who saw the television coverage of the escape of some and the rescue of others from the ruins of the Grand Hotel, Brighton that morning.

My recollection of events from the moment the IRA bomb that was intended to murder Prime Minister Thatcher exploded to departing the scene by ambulance are seared into my memory, but thereafter I lapsed into unconsciousness.

Steve Ramseys book is not only a graphic account of the events of that morning as it was seen through the eyes of the victims; it also details how the emergency services, police, hospital staff and the civil service were brought into what became an immensely complex operation. Initially there was no time for a textbook top-down operation, with senior staff taking control and issuing instructions to those on the scene.

As Ramseys book sets out, it was those dealing with events on the scene at the Grand Hotel and the Royal Sussex Hospital who took the decisions, in line with the military adage that no plan can ever withstand contact with reality.

At the scene, the policy that only the bomb squad could enter the immediate environment of a terrorist bombing until the possibility of a second, booby-trap weapon had been explored was ignored in order to rescue survivors.

At the Royal Sussex Hospital, it was impossible to refuse to identify casualties to the media, since live TV had broadcast the rescue of casualties as they were carried or stumbled out of the wreckage.

In many ways, however, the most important part of the book is its account of the meticulous work of the police forensic and investigative teams. They patiently worked to follow a tortuous path of clues which led to the identification, arrest and conviction of the IRA terrorist operative Patrick Magee, who had planted the bomb.

Sadly, those who planned, financed and commissioned the crime had not been brought to justice before they were guaranteed immunity by Prime Minister Blair.

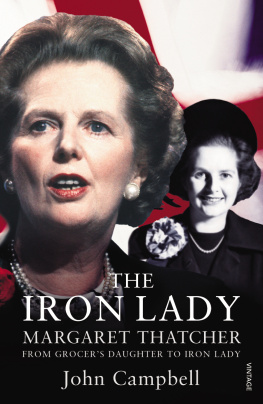

What has stood out ever since the Brighton bombing was the response of Prime Minister Thatcher. Despite such a close brush with death, only six hours later absolutely as scheduled she was on the platform at the Brighton Conference Centre to address not only her party, but the world. The message was clear. Cowardly terrorism had failed; courage and democracy had triumphed. The world took note. I was still barely conscious, but already the machinery of government was moving into action. My Department of Trade and Industry private secretaries, Andrew Lansley and Callum McCarthy, were soon setting up office in Brighton. After my wife and I were transferred to Stoke Mandeville Hospital two weeks later by helicopter, I began to resume control of my department from my hospital bed.

By Christmas I had had more than enough of hospital life, and discharged myself, having been invited to spend Christmas at Chequers with the Prime Minister and Denis Thatcher. Although I did return to Stoke Mandeville for Christmas lunch traditional hospital style with my wife. It was an extraordinary event.

The roast turkey, Brussels sprouts and roast potatoes arrived on a trolley from the operating theatre. The three consultant surgeons went to work carving the turkey with surgical skills. I began to laugh.

What is so funny? one of them asked. You three, I replied. Look at yourselves two Jews and a Palestinian not a Christian amongst you!

I think I learned something that day.

Indeed, the events recounted by Steve Ramsey suggest that we can, almost all of us, both do more and learn more under the stress of terrible events than we had ever thought likely.

Stress can be a powerful learning tool.

N ORMAN T EBBIT

May 2017

T hats definitely not thunder, said one police officer who had heard the noise, which came from the direction of Brightons Grand Hotel. The Prime Minister and many of her colleagues, in town for the Conservative Party conference, were inside. The air was dusty, and there were pieces of the hotel on the seafront. It was 2.54 a.m. on Friday 12 October 1984.

A police vehicle outside the Brighton Centre, next to the Grand, was shaken by the shockwave, and hit by dust so thick that it was almost like someone had thrown a blanket over the van, policeman Paul Parton recalls. I think my immediate thought was, gas explosion, or something like that. And then someone obviously said, Oh, IRA. And it was like, What, in Brighton?

Harvey Thomas, the conference organiser, came to in mid-air. When you dream youre flying through space, you kind of brush asteroids and things off, he says. But, in this case, they were bouncing off me, I was bouncing off them, and I realised: this is real.

Norman Tebbit,

At Brighton police station, about a mile away on John Street, Sergeant Paddy Tomkins heard the detonation. And then a couple of seconds later, the Tannoy directed all staff to respond. The connection was obvious.

Slightly further away, at Preston Circus fire station, a message came through that the Grands fire alarm was ringing. The message didnt say why. was all we knew on the way down. So, when we actually got there, it was a great surprise to us to see what we saw.

I remember jumping out the back of the van and the ground was covered in rubble, bricks, broken bricks, bits of railing off the front of the hotel and everything, policeman Paul Parton says.

And you could taste the dust and the mess. It was all up your nose and everything, and it was everywhere. And course youre trying to make your way forward to help people, and youve got eyes full of muck and stuff.

You couldnt see anything. In your mind you knew where the front of the building was, so you naturally move forward, gingerly. Well, you couldnt run, because of the state of the debris on the floor. And theres always that thing in your head what are you going to find? You dont know what youre going to find. You just move forward and deal with what comes up.

As we got closer and the dust was starting to settle, you could see [a policeman] laying on the ground, being supported by other policemen, people screaming, hanging off balconies, alarm bells ringing, water pouring out of broken pipes, and you could see the people up on the balcony. It was horrific, insomuch as, where do you go first?

The rubble covered the front door and the main part of the front hall, says PC Simon Parr.

People were going in through windows, getting people out, there were people in ball gowns there, there were nurses nearby whod been at a dinner and they were ripping their evening dresses to bandage the walking wounded as they were coming out. I remember the white and red dust. Everybody was covered in dust, because it was such a big hotel and such an old building. I remember just the incongruous nature of people in dinner suits and evening dresses, with blood on them, literally staggering as they were helped out through the windows and side doors.

As police officers in particular, everyone thinks youll be calm and know what to do. Well, of course, I dont think any of us had ever seen anything like it. But the basic instincts of policing are to get people out.

Here its suddenly got misty, said one of fire officer Fred Bishops colleagues, as their vehicle turned onto the seafront. Bishop recalls:

As we drove along the seafront, we suddenly became aware that this mist, as we thought it was Thats not quite mist. And suddenly we saw sheets, and pillowcases probably, and curtains and all sorts of material, hanging onto the lights that go along the seafront.

As soon as we stopped, obviously, we had a job to do. And I remember a policeman being there and I said to him, What actually happened? And he was completely foxed, really, because he said, Um, it just went bang. And he was kind of standing there thinking, What am I supposed to do? He was really confused, poor chap.