TRANQUEBAR PRESS

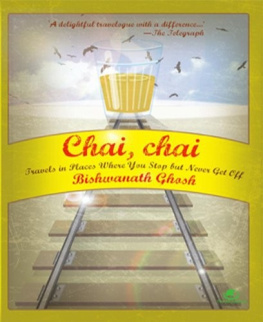

CHAI, CHAI

Bishwanath Ghosh was born in Kanpur, in Uttar Pradesh, in 1970. As a journalist, he worked in New Delhi for eight years before moving to southern India in 2001 to join the New Indian Express Group in Chennai. He has been with The Times of India and is presently deputy editor of The Hindu in Chennai.

He writes with the enthusiasm of an explorer, painting a rather adventurous picture of days spent in these seemingly non-destination towns.

Business Standard

To judge Chai, Chais literary merit, it might be appropriate to compare it with Pankaj Mishras celebrated 1995 Butter Chicken in Ludhiana. From an anthropological perspective, both books provide similar descriptions of small-town India:brash, clamorous and kitschy. But in tone they differ severely. Mishra distanced himself from his subject and took a pattronising view while Ghosh speaks with good-natured cultural tolerance.

The Hindu

Eccentric and funny, the short pieces in this book bring to life the sights and sounds of little-known towns.

The Telegraph

A travelogue with a difference. A unique aspect if his narrative is that Ghosh connects the history of these towns to his personal history. In that it becomes a reflective work, where the writer and his subjects are connected through shared memories.

Hindustan Times

Its Ghoshs keen sense of observation and the manner in which he express the mundane that makes the reader flip the pages.

New Sunday Express

Just five pages down, and you begin to see that the story of Chai, Chai is in the details that the writer has registered in simple, lucid prose. Ghosh infuses colour and flavor in everyday life, describing seemingly mundane chores and happenings with a sincerity that gently persuades you into revisiting certain sections of the book.

India Today Travel Plus

Chai, Chai makes for effortless reading, passing, strangely, almost as fast as the trains do through these unambitious stations. It is wistful, wondering how we are gradually letting all of the familiarities and distinctiveness of these towns mutate into a mindless worship of concrete and glass.

The Hindu

What works for Ghosh is his power of observation. He has definitely done the small towns a huge service, for otherwise, their stories are largely unheard in the din of English literature woven around urban India.

Deccan Herald

TRANQUEBAR PRESS

An imprint of westland ltd

Venkat Towers, 165, P.H. Road, Maduravoyal, Chennai 600 095

No. 38/10 (New No.5), Raghava Nagar, New Timber Yard Layout, Bangalore 560 026

Survey No. A - 9, II Floor, Moula Ali Industrial Area, Moula Ali, Hyderabad 500 040

23/181, Anand Nagar, Nehru Road, Santacruz East, Mumbai 400 055

4322/3, Ansari Road, Daryagang, New Delhi-110002

First published in TRANQUEBAR by westland ltd 2009

Copyright Bishwanath Ghosh 2009

All rights reserved

ISBN: 9789380032863

Typeset in Bembo by SRYA, New Delhi

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, circulated, and no reproduction in any form, in whole or in part (except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews) may be made without written permission of the publishers.

For my parents,

Karabi and Samir Ghosh

CONTENTS

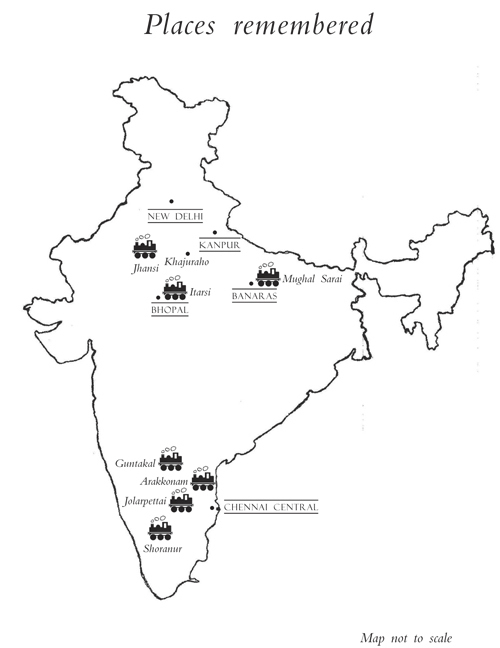

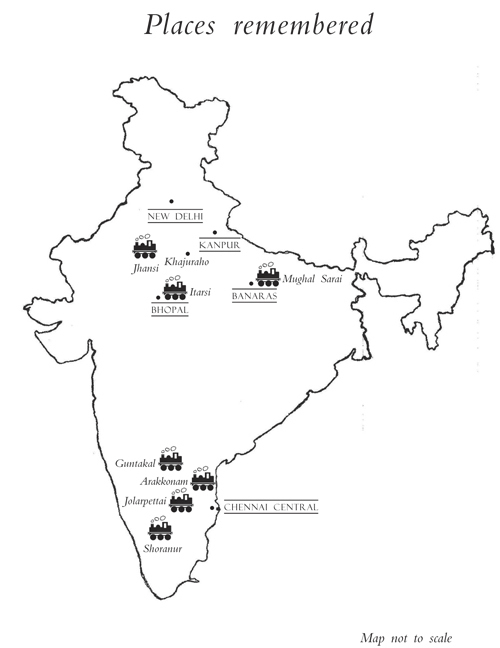

Tiny Towns: Jumbo Junctions

Mughal Sarai

Jhansi

Itarsi

Guntakal

Arakkonam and Jolarpettai

Shoranur

Railway stations in India stand like fiercely independent states within cities and towns, insulated from the local flavour, as if they are territories of a common colonial master sitting in Delhi, which they are anyway. Such is their sameness that if you remove the yellow slab that identifies the station and all other signboards, you will have very little idea where you are. All you will know is that you are in a country where tea is available round the clock and whose inhabitants have two primary occupationstravelling and waiting.

If you have been waiting for a while, you might find a clue though about your whereaboutswhen the vendors yell at each other in the local language, or when an announcement on the PA system comes up. If the announcement is made in Tamil, apart from the standard Hindi and English, you know you are in Tamil Nadu. But where exactly in Tamil Nadu? It could be Madurai or Coimbatore. As cities, each of them has a distinct identity. But sitting at the railway station, it is almost impossible to tell one from the other. And when you are travelling in a long-distance train like the Tamil Nadu Express, it is often not possible to tell Tamil Nadu from Andhra Pradesh, or Andhra Pradesh from Maharashtra. You will have to rely on the chaiwallah to tell you your current location, in case youve missed the yellow signboard.

India can have no better symbol for national integration than the railways. The railway reservation form doesnt ask you anything beyond your name, age, gender and address. In trains, people of two castes who would otherwise not like to be seen in each others company, cohabit without fuss for hours, even a couple of days. A millionaire who travels in a first-class air-conditioned compartment to maintain his exclusivity is forced to share the makeshift bedroom with a much poorer countryman who happens to be travelling on office expense. In the air-conditioned coupe, they are equals: the rich man putting up with the snoring of the poor.

The journeys are not just about the levelling, but also about getting acquainted with each others cultures, especially food habits. Marwaris, when they travel as a large family, carry a stock of food that would last them the journey. The piles of puris are in proportion to the number of travelling members, the eating capacity of each member, and the number of meals they would have on the train. Just when you are hungry and waiting for the pantry-car boy to deliver your meal, you find them taking the lid off their food basket and releasing into the compartment the delicious whiff of puri, sabzi and pickles. It is the youngest of the women who usually opens the basket. The men, starting with the eldest, are served first. At times there are so many puris being passed around that I have felt tempted to ask, Can I have a couple of them, please?

Tamil families usually carry their stock as well: idlis and an oily paste of what they call the chutney powder. The idli has always been my weakness, and I have always imagined the round, steel tiffin-box being extended to me: Mind having one? But I have always looked away while the steel box is being passed around. Bengalis, on the other hand, rarely carry food: for them, the train journey is another excuse to eat out. After eating, they would compare if the chicken curry was as good as the one served on Rajdhani Express six months ago. Most often it isnt. But thats a different story. The story here is that the railways are not just a means of transport, but the circulatory system of India. No railways, no India. We all know that, dont we?