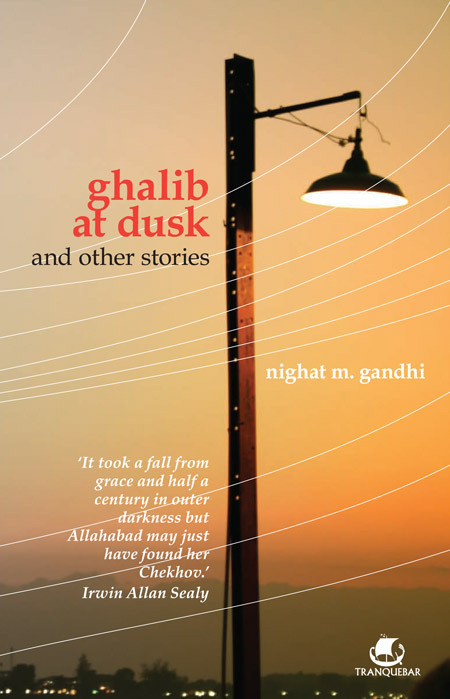

TRANQUEBAR PRESS

GHALIB AT DUSK & OTHER STORIES

Nighat M. Gandhi is a writer and professional mental health counsellor. She spent her formative years in Dhaka and Karachi. After her college years in the USA, she married and moved to Allahabad, where she raised her two daughters, and became involved in womens rights activism. She writes for Indian and Pakistani newspapers, such as The Hindu, Hindustan Times and Dawn .

westland press

571, Poonamallee High Road, Kamraj Bhawan, Aminijikarai, Chennai 600 029

No. 38/10 (New No.5), Raghava Nagar, New Timber Yard Layout, Bangalore 560 026

Survey No. A-9, II Floor, Moula Ali Industrial Area, Moula Ali, Hyderabad 500 040

Plot No. 102, Marol Coop Ind Estate, Marol, Andheri East, Mumbai 400 059

47, Brij Mohan Road, Daryaganj, New Delhi 110 002

First published in TRANQUEBAR PRESS by westland ltd 2009

The Publishers wish to acknowledge the publications in which the following stories first appeared:

Risk in Prism International, Canada and also in COSAW Bulletin, USA.

Fishing At Haleji in Short Story International, USA.

In Lieu of Gold in The Literary Review, USA and also in The Toronto Review.

Hot Water Bag in The Literary Review, USA.

An Undelivered Letter in The Antigonish Review, Canada.

Love: Unclassified in Psychological Foundations, India.

Family Duty in Short Story International, USA.

Trains in Asia Literary Review, Hong Kong.

Translation Credits :

Ghalibs couplets: Hai kahan tammana ka by Frances Pritchett; Ashiqi sabr-talab by Sarfaraz K. Niazi; Bahaaro mera jeevan lyrics by Kaifi Azmi, film Aakhri Khat, sung by Lata Mangeshkar.

Copyright Nighat M. Gandhi 2009

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-93-80032-85-6

Typeset in Sabon Roman by SRYA, New Delhi

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, circulated, and no reproduction in any form, in whole or in part (except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews) may be made without written permission of the publishers.

To the people of Bangladesh, Pakistan and India

who will bring lasting peace to these lands

where I belong

THANKS TO MAYA for knocking with me at the doors of major publishing houses in Delhi with my short stories, and for cradling my dejection when none of them contacted me. Many thanks to Arpita for suggesting Westland who valued the manuscript enough to accept it for publication. I would also like to thank friends in India and Pakistan who read and commented on the stories in various stages of completion. Heartfelt gratitude to Ammi and Abba for all the growing up experiences, which unwittingly made me the writer I turned out to be. To Raj for his unwavering support and insightful critique of my writing. To Afreen and Suroorthe two most amazing, independent young women in my lifefor being my staunchest allies, for believing in me as a writer before I did, and for bolstering my shaky confidence by awarding me the coolest Mom on earth accolade.

THE FIRST FIVE stories in this collection are set in Karachi of the early 90s, and the rest take place in India, where Ive lived off and on since the mid-90s. Geographically speaking, Bangladesh gave me my early childhood, Pakistan my adolescence, and India, my adulthood. Genetically speaking, I am a hybrid breed, born of part Bengali-Memon parentage, into a family of poor Muslim immigrants who moved from West to East Bengal in the wake of Partition. The soils of three South Asian nations have fertilized my cross-cultural upbringing. What has such an itinerant background given me? A mongrel childhood, a culturally cross-pollinated adulthood. Can my socio-cultural-political compass point to any one of these countries to the exclusion of others? In 1972, my family underwent yet another migration. We left Bangladesh when it was no longer East Pakistan. At that time I spoke Bengali fluently, but not Urdu. Later, in Pakistan, I was made to forget Bengali, and told Urdu was my mother tongue. Still later, as a result of my English language education, I started writing in English.

I am told that there are no contemporary writers who live and write in India and Pakistan, crossing the inimical border between the two nations with equal ease and familiarity. If I do so, I reflect a truly intricate social reality in doing what few others are allowed to, or able to do. Mine is a lived engagement with that reality, entwining my life intimately with other liveswith relatives, friends, peace activists, artists and writerson both sides of the border. Friendships and familial bonds have made me sprout roots in both countries, and have made me embrace a South Asian cultural identity, a composite individuality that is broader than the fixed and narrow official definitions passports and visas assign.

I do different kinds of relating in India and Pakistan. I feel freer as a woman in India in some ways, to move around and travel alone, but even in India, the democratic space for voicing dissent appears to be shrinking, whether against Hindutva or at the lack of critical self-reflection among Muslims, especially after Gujarat 2002. There are of course, many more limitations in Pakistan on such outspokenness, and there are many more constraints on freedom of mobility for women. In Pakistan its harder to come across women that society deems respectable, who are unaccompanied by men in public spaceswomen without head cover, women freely hopping onto buses and trains. I remember the quiet serenity of my adolescent years in Karachi when we hadnt heard the term Islamic fundamentalism and I had hardly seen any women in hijaab. How times have changed since then. Now on my visits to Pakistan, it hurts having to prove my credentials as a Muslim woman to self-appointed guardians of Islam who claim moral superiority by sporting body hair as beards, or by concealing it under a headscarf. I am looked at askance for wearing my hair short, for not hiding it, for insisting on my right to be attended to as a woman in offices and not as a mans accompanied baggage, for choosing to travel alone by bus, cab, and rickshaw. In my travels and in my conversations with ordinary men and women in Pakistan, I see the ingenious social creativity people practice in their personal spheres, but the constraints on uninhibited expressiveness in the arts can be tangibly felt, and I hurt all the more, sensing those wounds as mine.

Recently while looking for the exact meaning of the Urdu phrase Bazeecha-e-atfaal to include in this prefacefrom the first Ghalib couplet Abba, my father, introduced me to as a childI came across the proverb Ba Musalmaan Allah, Allah, ba Brahmin Ram, Ram (when with a Muslim, chant Allah, Allah; when with a Brahmin, chant Ram, Ram) in my Urdu dictionary. I loved this irreverent yet relevant aphorism for our timesI couldnt help thinking if only we had the generosity of spirit to chant Allah Allah and Ram Ram with equal eloquence and detachment, India and Pakistan would have evolved as two peaceful nations by now. But back to that couplet of Mirza Ghalibs: