DOPESICK

Dealers, Doctors & the Drug Company that Addicted America

Beth Macy

AN APOLLO BOOK

www.headofzeus.com

Beth Macy takes us into the heart of Americas struggle with opioid addiction. From distressed small communities in Central Appalachia to wealthy suburbs and once-idyllic farm towns, this powerful and moving story illustrates how a national crisis became so firmly entrenched.

At the heart of the narrative is a large corporation, Purdue whose owners are celebrated for their sponsorship of art galleries and museums that targeted areas of the country already awash in painkillers and encouraged small town doctors to prescribe OxyContin, a highly addictive drug. Evidence of its capacity to enslave its users was suppressed. Macy tries to answer a grieving mothers question why her only son died and comes away with a harrowing story of greed and need.

Overtreatment with painkillers became the norm. In distressed communities of ex-miners and factory workers, the unemployed used painkillers both to numb the pain of joblessness and pay their bills. Macys portraits of the families, cops and doctors struggling to ameliorate this epidemic are unforgettable. But in a country unable to provide basic healthcare for all, Macy still finds reason to hope that there may be a decent future for people so abandoned by their political leaders. This is an essential book for anyone trying to understand the harrowing realities of Trumps America.

Contents

This evil is confined to no class or occupation. It numbers among its victims some of the best women and men of all classes. Prompt action is then demanded, lest our land should becomestupefied by the direful effects of narcotics and thus diseased physically, mentally, and morally, the love of liberty swallowed up by the love of opium, whilst the masses of our people would become fit subjects for a despot.

Dr. W. G. Rogers, writing in The Daily Dispatch (Richmond, VA), January 25, 1884

A mothers love for her child is like nothing else in the world. It knows no law, no pity, it dares all things and crushes down remorselessly all that stands in its path.

Agatha Christie, The Last Sance (from The Hound of Death and Other Stories )

In memory of Scott Roth (19882010), Jesse Bolstridge (19942013), Colton Scott Banks (19932012), Brandon Robert Perullo (19832014), John Robert Bobby Baylis (19862015), Jordan Joey Gilbert (19892017), Randy Nuss (19842003), Arnold Fayne McCauley (19342009), Patrick Michael Stewart (19802004), Eddie Bisch (19822001), Jessee Creed Baker (19822017), and Theresa Helen Henry (19892017)

In 2012, I began reporting on the heroin epidemic as it landed in the suburbs of Roanoke, Virginia, where I had covered marginalized families for the Roanoke Times for two decades, predominantly those based in the inner city. When I first wrote about heroin in the suburbs, most families I interviewed were too ashamed to go on the record.

Five years later as I finished writing this book, nearly everyone agreed for their names to be used, with the exception of a few, as noted in the text, who feared going public would jeopardize their jobs or their safety.

Im indebted to the families I first met in 2012 who allowed me to continue following their stories as their loved ones grappled with rehab and prison, with recovery and relapse. Im also grateful for insights gleaned from several rural Virginia families, advocates, and first responders, many of whom were quietly battling the scourge almost two decades before I appeared on the scene. Several law enforcement officials spoke with me on background and on the record, including a few who had arrested their own relatives for peddling dope. So did scores of doctors and other caregivers who, after working fourteen-plus-hour days, did not feel their work was complete without getting the story of this epidemic out there.

A few interviewees died before I had time to transcribe my notes, including one by his own hand after relapsing and fearing that his wifewhom he loved more than anything in the worldwould divorce him. If she ever figures out she dont need me, he confided, Im screwed.

Their survivors continued talking to me during their most fragile moments, generously texting and calling and emailing photographs long after their loved ones battles were over. One requested my MP3 recording of her departed loved ones interview, so desperate was she to hear his voice again. Another shared her deceased daughters journals.

Im particularly indebted to four Virginia moms: Kristi Fernandez, Ginger Mumpower, Jamie Waldrop, and Patricia Mehrmann. More than anyone, they helped me understand the crushing and sometimes contradictory facets of an inadequate criminal justice system often working at cross-purposes against medical science, and a health care bureaucracy that continues pumping out hard-core pain pills in large doses while seeking to quell cravings and turn around lives with yet more medication.

In sharing their experiences, these mothers hoped readers would be moved to advocate for life-saving addiction treatment and research, health care and criminal justice reform, and for political leadership capable of steering America out of the worst drug epidemic in modern history. Until then, they hoped their childrens stories would illuminate the need for patients not only to become more discerning consumers of health care but also to employ a healthy skepticism the next time a pharmaceutical company announces its latest wonder drug.

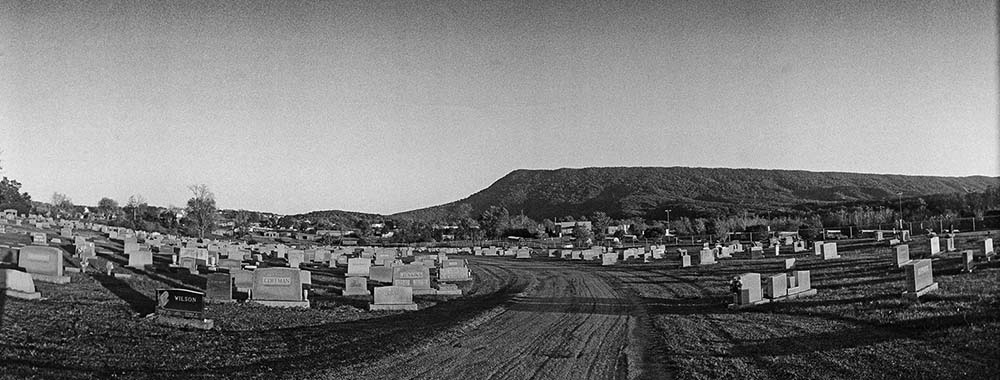

Riverview Cemetery, Strasburg, Virginia

of Hazelton Federal Correctional Institution on the outskirts of Bruceton Mills, West Virginia. The air was so thick that the flags framing the concrete-block structure hung there drooping, as still as the razor wire that scalloped the roofs.

as the countys largest employer, with eight hundred guards and staff.

as of today that was involved with my case? he wanted to know. What personal information about him did I intend to use?

Jones agreed to let me visit, finally, because he wanted his daughters, in kindergarten and first grade when their dad was arrested in June 2013, to understand theres a different side of me, as he put it. The last theyd seen him, a week before his arrest, he had delivered birthday cupcakes to their school.

I thought of the tsunami of misery Jones had first unleashed in Woodstock, Virginia, as his prosecutor put it, before it fanned out in waves over the northwestern region of the state and into some of Washingtons western bedroom communities in 2012 and 2013. In just a few months time, Jones was presiding over the largest heroin ring in the region, transforming a handful of users into hundreds.

As I made my way to the prison, I calculated the human toll, the hundreds of addicted people who ended up dopesick when their heroin supply was suddenly cut by Joness arrest: throwing up and sweating and shitting their pants. When Jones was jailed in 2013, many of the newly addicted Woodstock users began carpooling to the nearest big citiesBaltimore, Washington, and even Martinsburg, West Virginia, aka Little Baltimoreto score drugs, converging on known heroin hot spots and playing drug-dealer Russian roulette.