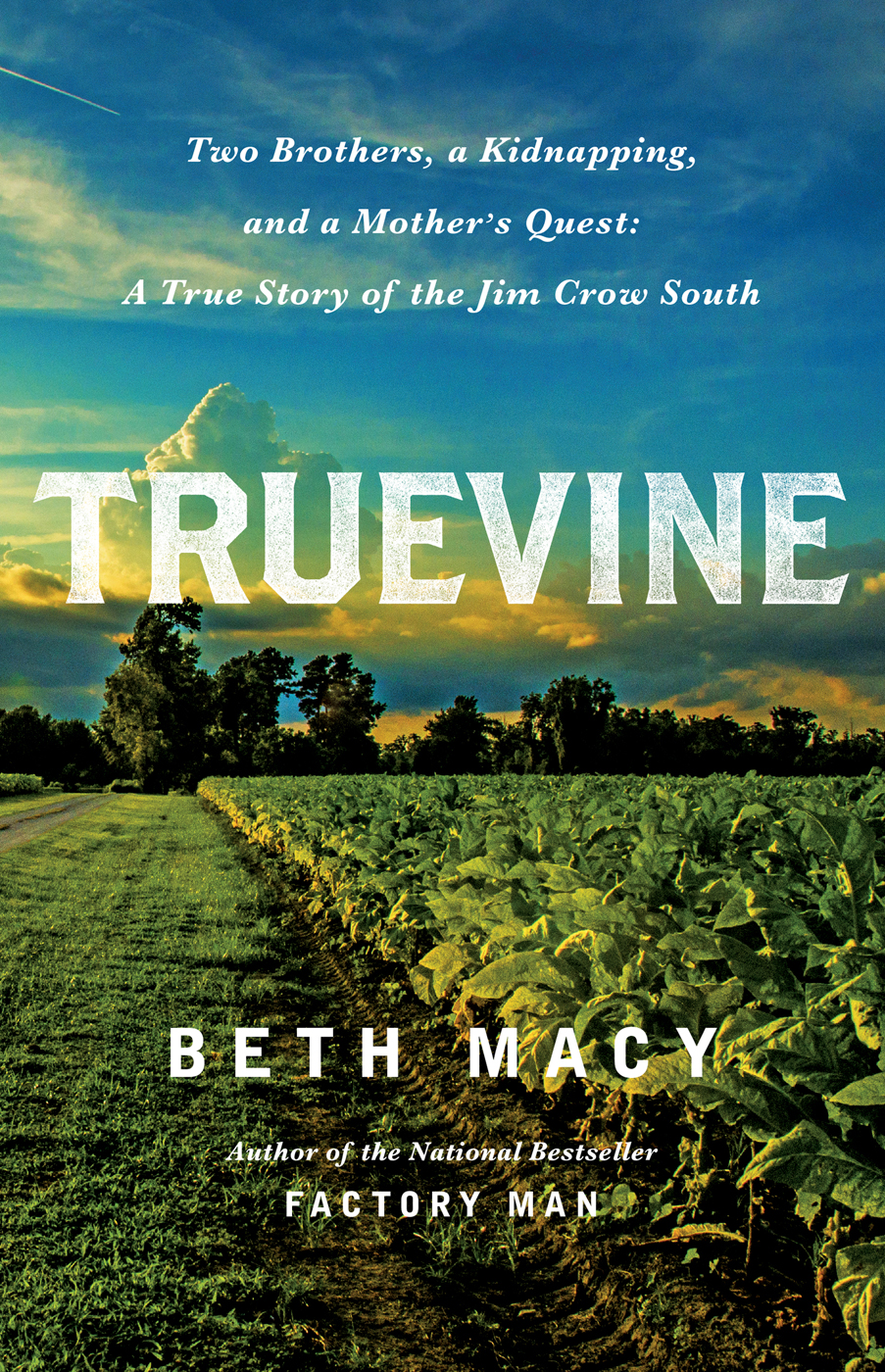

I am the true vine, and My father is the vinedresser. Every branch in Me that does not bear fruit He takes away; every branch that bears fruit He prunes, that it may bear more fruit.

John 15:12

For the first time he sought to analyze the burden he bore upon his back, that dead-weight of social degradation partially masked behind a half-named Negro problem. He felt his poverty; without a cent, without a home, without land, tools, or savings, he had entered into competition with rich, landed, skilled neighbors. To be a poor man is hard, but to be a poor race in a land of dollars is the very bottom of hardships.

W. E. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk

T heir world was so blindingly white that the brothers had to squint to keep from crying. On a clear day, it hurt just to open their eyes. They blinked constantly, trying to make out the hazy objects in front of them, their brows furrowed and their eyes darting from side to side, unable to settle on a focal point. Their eyes were tinged with pink, their irises a watery pale blue.

Their skin was so delicate that it was possible, looking only at the backs of their hands, to mistake the young African-American brothers for the kind of white landed gentry who didnt have to eke out a living hoeing crabgrass from stony rows of tobacco or suckering the leaves from the stems.

That was as true when they were old men as when they were little boys, back when a white man appeared in Truevine, Virginia, as their neighbors and relatives remembered itthat very bad man, they called him.

Back when everything they knew disappeared behind them in a cloud of red-clay dust.

The year was 1899, as the old people told the story, then and now; the place a sweltering tobacco farm in the Jim Crow South, a remote spot in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains where everyone they knew was either a former slave, or a child or grandchild of slaves. George and Willie Muse were just nine and six years old, but they worked a shift known by sharecroppers as can see to cant seedaylight to dark. Can to cant, for short.

Twenty miles away and twenty-seven years earlier, a man born into slavery named Booker T. Washington had walked four hundred miles from the mountains to the swampy plains, to get himself educated at Hampton Institute. It was a whole race trying to go to school, he would write.

Forty miles in the other direction, another former slave, named Lucy Addison, had gotten herself educated at a Quaker college in Philadelphia. In 1886, Addison landed in the railroad boomtown of Roanoke, Virginia, where she set up the citys first school for blacks in a two-story frame building with long benches and crude desks, using hand-me-down books from the citys white schools. She became such an icon of education that some elderly African Americans still have her faded portrait hanging on their walls, right next to the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. and President Obama. Addison inspired Ed Dudley, a dentists son who would become President Trumans ambassador to Liberia. She taught future lawyer Oliver Hill, who would grow up to help overturn the separate-but-equal laws of the day in the landmark decision Brown v. Board of Education.

But such leaps were unheard of for black families in Truevine, where it would take decades before most learned to read and write. While Washington was on his way to fame and the founding of Tuskegee Institute, black children in Truevine were kept out of school when the harvest came in.

They had too much work to do.

Still, in this remote and tiny crossroads, where everyone knew everyone for generations back, George and Willie Muse were different. They were genetic anomalies: albinos born to black parents. Reared at a time when a black man could be jailed or even killed just for looking at a white womanreckless eyeballing, the charge was officially calledthe Muse brothers were doubly cursed.

Their white skin burned at the first blush of sun, and their eyes watered constantly. They squinted so much that they began to develop premature creases in their foreheads. So they looked down as they workedthey always looked downheeding their mothers advice to never look toward the sun.

Harriett Muse was fiercely protective. She cloaked her boys in rags to keep their skin from blistering, and for the same reason she made them wear long sleeves when it was 100 degrees. When a vicious dog happened onto the tenant farm where they worked and lunged at little Willie, she chased it away with an iron skillet. She made the boys favorite food, ash cakes, a simple corn bread baked over an open fire.

When it snowed she cobbled together a dessert called snow cream out of sugar, vanilla, eggs, and snow. When a rainbow appeared above the mountain ridges, she told them to take solace in it. Thats Gods promise after the storm, she said.

She spoiled them as much as a poor sharecropper could, but George and Willie were expected to work, walking the rows of tobacco looking for bugs and picking budworms off the leaves when they found them, squashing them between their fingers as they went.

The boys were squinting, as they usually were, when the bad man appeared. What a surprise the well-heeled stranger was in this hodgepodge of dirt roads, tobacco barns, and shacks where tenants stuffed newspapers into holes in the walls to keep critters out, and the only dependable structure for miles was a white-frame meeting hall that doubled as a one-room schoola school the black community built by hand because the county provided a teacher but not a building for him to teach in.