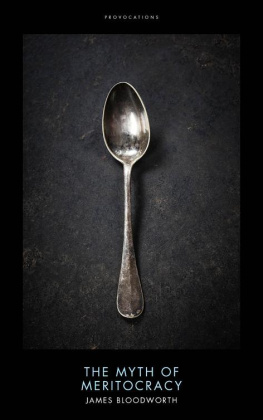

An extraordinary and unsettling journey into the way modern Britons work.

It is Down and Out In Paris and London for the gig economy age.

Matthew dAncona, Guardian columnist and bestselling author of Post-Truth

A tautly written expos of the swindle of the gig economy and a call to arms.

Nick Cohen, journalist and author of Whats Left?

I emerged from James Bloodworths quietly devastating and deeply disturbing book convinced that the gig economy is simply another way in which the powerful are enabled to oppress the disadvantaged.

D. J. Taylor, author of Orwell: The Life

A truly devastating examination of the vulnerable human underbelly of Britains labour market, shining a bright light on the unjust and exploitative practices that erode the morale and living standards of working-class communities.

Frank Field, MP

James Bloodworth pulls back the carpet and exposes the rotten floorboards of Britains low-wage, insecure and exploitative economy, describing living and working conditions that Dickens would recognise. It must surely act as a wake-up call to our political elites to genuinely tackle the gross inequality at the heart of our society.

Wes Streeting, MP

Whatever you think of the political assertions in this book and I disagree with many of them this is an important investigation into the reality of low-wage Britain. Whether you are on the Right, Left or Centre, anybody who believes in solidarity and social justice should read this book.

Nick Timothy, former Chief of Staff to Theresa May, now columnist for the Daily Telegraph and The Sun

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

James Bloodworth is a journalist, broadcaster and author. He writes a weekly column for the International Business Times and his work has appeared in the Guardian, New York Review of Books, New Statesman and Wall Street Journal. He is the former editor of Left Foot Forward, an influential political blog in the UK.

@J_Bloodworth

@J_Bloodworth

Published in trade paperback in Great Britain in 2018 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright James Bloodworth, 2018

The moral right of James Bloodworth to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 014 8

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 015 5

Printed in Great Britain.

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

2627 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

CONTENTS

Life is good, and joy runs high

Between English earth and sky

William Ernest Henley,

England, My England

PREFACE

Early in 2016, as the sun crept out from behind the clouds and the bitter winter frosts began to subside, I left London in a beaten-up old car to explore a side of life that is usually hidden from view.

Around one in twenty people in Britain today live on the minimum wage. Many of these people live in towns and cities that were once thriving centres of industry and manufacturing. Many were born there and an increasing number were born abroad.

I decided that the best way to find out about low-paid work in Britain today would be to become a part of that world myself: to sink down and become another cog in the vast, amorphous and impersonal machine on which much of Britains prosperity is built. I would penetrate the agencies that failed to pay their staff a living wage. I would live among the men and women who scratched a living on the margins of a prosperous society that had supposedly gone back to work after a long, drawn-out recession. And I would join the growing army of people for whom the idea of a stable, fulfilling job was about as attainable as lifting an Oscar or the Ballon dOr.

In the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2008, austerity became the raison dtre of the British government. There was no money left so it was confidently proclaimed and public services had to be cut back drastically or else contracted out to private companies who supposedly knew better how to run them than the state.

Since then the mood music has grown more optimistic: Britain is enjoying record levels of employment. Yet sunny optimism about the labour market masks the changing nature of the contemporary economy. More people are in work, but an increasing proportion of this work is poorly paid, precarious and without regular hours. Wages have been failing to keep pace with inflation. A million more people have become self-employed since the financial crisis, many of them working in the so-called gig economy with few basic workers rights. Toiling away for five hours a week may keep you off the governments unemployment figures, but it is not necessarily sufficient to pay the rent. Even for those in full-time work the picture is hardly rosy: Britain has recently experienced the longest period of wage stagnation for 150 years.

I set out to write about the changing nature of work, but this is also a book about the changing nature of Britain. Half a century ago Arthur Seaton, the anti-hero of Alan Sillitoes cult novel Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, may have hated his dull job as a lathe worker in a Nottingham factory, but he could at least take a day off now and then when he was ill. There was a union rep on hand to listen to his grievances if the boss was in his ear. If he did get the sack he could usually walk into another job without too much fuss. There were local pubs and clubs at which to drink and socialise after work. All in all, there was a definite sense that, while the struggle between bosses and workers was not at an end, there had been a fundamental change in its terms.

The social democratic era probably ended in 1984, when the police batons came crashing down onto the heads of working men whom the former Conservative Prime Minister Harold Macmillan had once described as the best men in the world, who beat the Kaisers and Hitlers armies and never gave in. The stunned faces of the miners, knocked for six by the police and plastered luridly across the tabloids, seemed to capture the realisation of the time that, after a brief interregnum, to be a working man or woman was once again to be, if not despised, then only just tolerated.

Life in Britain has improved a great deal for many over the past forty years. Unthinking nostalgia is a dead end, the equivalent of an attempt to reside in the ruins of a crumbling old house that is full of cobwebs and on the verge of collapse. A sepia-tinged yearning for the mid-twentieth century is especially insulting to those for whom the century of the common man was just that: the century of the white, heterosexual

Next page

@J_Bloodworth

@J_Bloodworth