FOR ANGELINA, JULIET, NICOLAS, AND GEORGE

CONTENTS

J ohn Alite was a murderer, drug dealer, and thug.

Over the course of a twenty-five-year career as a gangster he brutalized people: stabbing them, shooting them, beating them with pipes, blackjacks, and baseball bats. Hes not proud of that, but he doesnt try to hide from it, either. Its who he was.

But its not who he is.

At least thats his position today, in 2014, as he tries to put his life back together, a fifty-year-old former mob associate and hit man trying to live a normal life, trying to figure out how he got off track, and trying to get back on.

Sometimes I wonder what happened, he says.

A lot of people do.

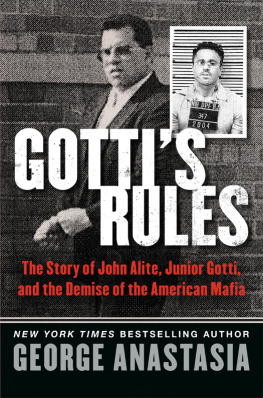

The simple answer is that he did what he did to make money, to live well and to enhance his position in the Gambino crime family. He did most of it, he says, on the orders of John A. Gotti (known as Junior) and sometimes on the orders of John J. Gotti, Juniors father. Two federal court juries in New York heard Alite tell parts of his story. One came back with a conviction. The other couldnt decide.

Alites story, from where he is sitting, is a graphic and often brutal look at organized crime. Take a step back, however, and his experiences, detailed in debriefing sessions with the FBI, in testimony from the witness stand, and in hours of interviews for this book, are part of the bloody and treacherous tapestry that describes the demise of the American Mafia. The once powerful, monolithic, and highly secretive criminal organization has lost most of its clout in the American underworld, a victim of multi-pronged federal prosecutions and the deterioration of a value system that held it together for decades.

Alite (pronounced -Lite) took the stand in 2009 at the trials of mob soldier Charles Carneglia and mob boss Junior Gotti. Carneglia was convicted of racketeering and murder. He is serving a life term. Gotti beat the case after a jury hung, almost evenly deadlocked on all three counts. Like Alite, Junior is now a free man and putting his own spin on this story. He denies most of the allegations made by Alite, including charges that he dealt drugs and killed, or ordered the murders of, several individuals.

Junior also has denied that he ever cooperated with authorities. There is an FBI document that will be detailed later in this book that refutes that claim. Known as a 302the numerical designation for a memo summarizing a debriefing sessionthe five-page memo outlines a meeting on January 18, 2005, in which Gotti Jr. and two of his defense attorneys met with federal prosecutors and FBI agents at the U.S. Attorneys Office on Pearl Street in lower Manhattan.

Jerry Capeci, the dean of mob reporters in America, broke the first story about Juniors attempt to cooperate. The 302, which had never before been made public, expands and confirms Capecis report, which was based on sources. The meeting was described as a proffer session, a negotiation in which a target or potential defendant agrees to tell authorities what he knows in an attempt to work out a plea and cooperation deal. Nothing that is said during one of these sessions can be used against the target or against anyone else if an agreement is not worked out.

Junior and his lawyers apparently never completed the deal, but that didnt keep them from trying. And, as the document indicates, it didnt stop Junior Gotti from giving up information about murders, corrupt cops and politicians, his crime familys influence in the Queens District Attorneys Office, and his own wheeling and dealing, including a plan he and an associate had to turn a city garbage dump into the site for a new Bronx House of Detention, which he would sell to the city for $20 million.

Let Junior Gotti and his lawyers spin that information any way they choose. The document speaks for itself. There was no attempt while writing this book to interview anyone in the Gotti camp. To turn Alites story into a he said, they said narrative would serve no purpose.

The Gottis deny virtually everything Alite alleges. Alite, on the other hand, denies very little. His version of the events that marked his lifea version that federal authorities adopted when they put him under oath on the witness standis a story of murder, money, and betrayal. Its one mans life of crime, a seduction of sorts that made him rich, turned him terribly violent, and very nearly got him killed on a dozen different occasions.

It may also be a story of redemption, but thats a question that cant be answered at this point.

The backdrop is the Gotti family and the American Mafia; more accurately, the Gotti family and the demise of the American Mafia. No one individual has had more to do with the once secret society coming apart at the seams than John J. Gotti.

Gotti was a mob boss who loved the spotlight, a celebrity gangster who thumbed his nose at the conventional wisdom of the old-time wiseguys. Their idea was to make money, not headlines. Gotti thought he could do both. For a long time he did. He and his son embodied the Me generation of the mob. Junior (for the purpose of this story hes referred to as Junior even though he and his father had different middle names) was a spoiled, self-absorbed second-generation gangster whose sense of entitlement was his undoing. He was all about status and power. He liked the idea of being a mobster, but never really understood how it worked.

Smug and arrogant, bullies in expensive suits, the Gottis played by their own set of rules, rules that allowed them to do whatever they wanted to whomever they wanted.

That was part of the hypocrisy of the Gotti crime family. The image they projected didnt mesh with the reality. Even the Dapper Don moniker was phony, according to Alite. If Gotti Sr. didnt have an associate picking out his clothes and telling him how to dress, the former thug and hijacker would have dressed like, well, a thug and hijacker, clashing plaids and stripes and colors rather than the cool, sophisticated elegance that became his trademark.

The media, of course, helped create the image. John J. Gotti on the cover of Time magazine; in boldface on Page Six of the New York Post; a sound bite, a pithy quote, leading the evening news. John Gotti was the face of the American Mafia at the end of the twentieth century.

And his son, coming on his heels, extending the reign.

It could be argued that Cosa Nostra was on the way out even before the Gottis got onstage. Second- and third-generation Italian Americans, in fact, make lousy gangsters. The best and the brightest in that community are now doctors, lawyers, educators. The mob is scraping the bottom of the gene pool.

Thats where the Gottis were located.

Add more sophisticated law enforcement, high-tech electronic surveillance, and the RICO Act and its clear the deck was stacked against the American Mafia. Throw in the death of omert, the code of silence that was the foundation for the wall of secrecy that once protected the honored society. And also consider this: the Mafia was always a front, a faade, a fugazy if you will. Mario Puzo, Francis Ford Coppola, and Martin Scorsese have built stories around the life, and the public has developed a perception based on those wonderfully written, directed, and acted fictions.

The reality is that if there ever was nobility and honorand Im not sure there wasit disappeared two or three generations ago. The American Mafia took the value system of the Italian-American community and bastardized it for its own benefit. The concepts of honor, fierce family loyalty, and respect, concepts that were and are as common and as expected in most Italian-American homes as spaghetti and meatballs for dinner on Sunday, were twisted into a code of conduct that lent power and status to outlaws and thugs.

Next page