ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

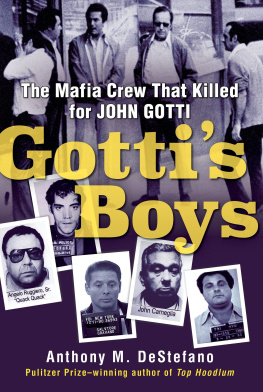

This is the seventh book I have written about organized crime and doing each has made me feel like an archeologist of La Cosa Nostra. I have had to dig back in time, sometimes decades ago, to piece together the stories. In Gottis Boys, the time span covered was not as long as it was on Top Hoodlum, my book about Frank Costello, which went back to the early part of the twentieth century in old New York, but the amount of work was about the same. Luckily, I had some good help along the way and access to great material. As is usual in a book about the mob, some people helped me and prefer to remain anonymous. They know who they are and get my thanks.

There exist numerous court files and judicial decisions about the crimes of John Gotti and his crew. Much of that material can be found in electronic databases, including the federal PACER system of accessing files. Still, I had to dig back into some old paper court files that are kept in the National Archives, where the staff in the Northeast Region office in Manhattan assisted me. My thanks again to Kevin Reilly and Trina Yeckley of the regional office. In Savannah, Georgia, Anne Butler of the Live Oak Public Library assembled old news clips from microfilm for me.

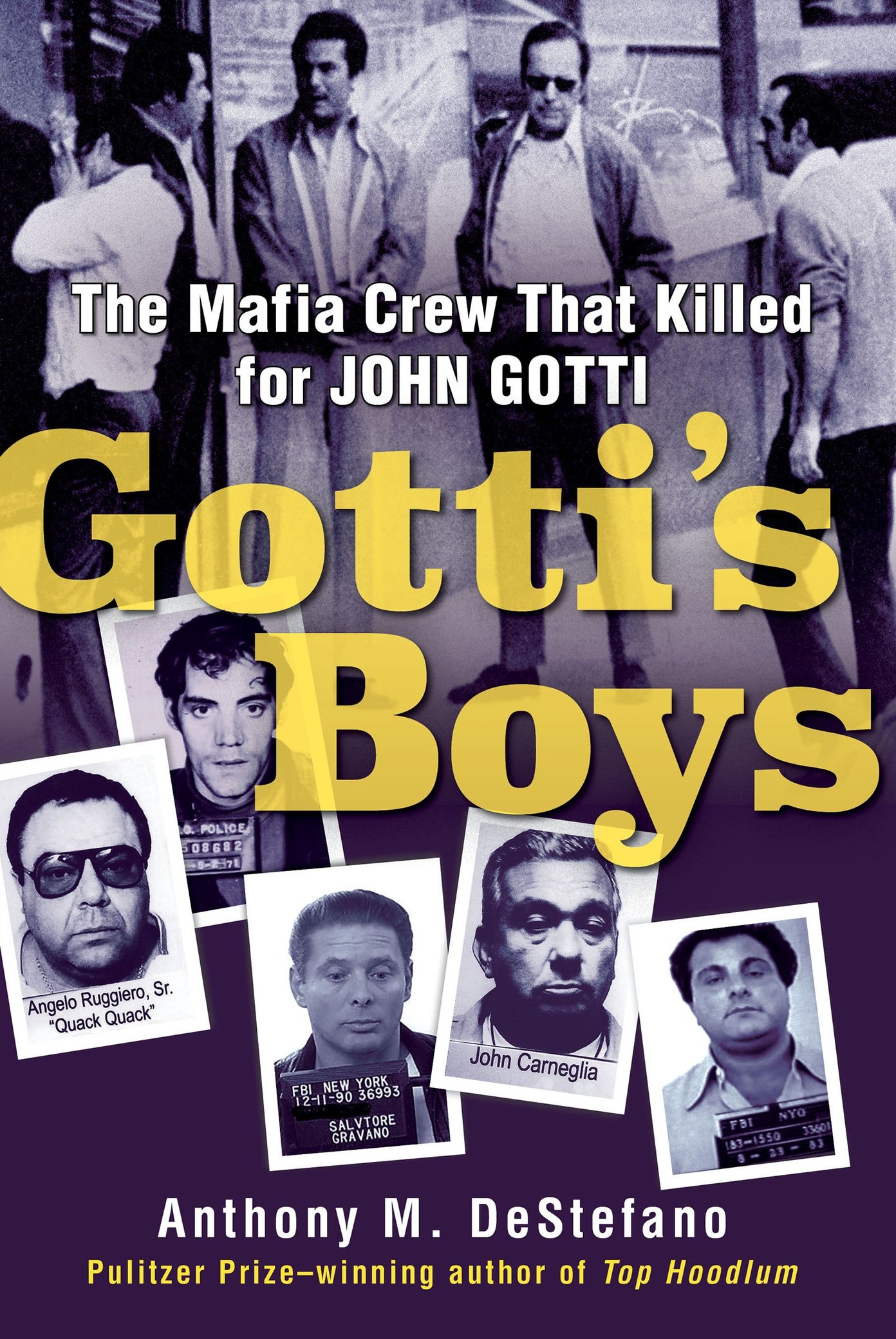

A number of current and former federal officials provided critical assistance. Over at the Drug Enforcement Administrations New York office, special agent in charge James Hunt and his key spokesperson, Erin Mulvey, provided important historical perspective and photographs. At the FBI, spokesperson Amy Thoreson smoothed the way in setting up interviews and seeking additional photographs. Although she no longer is a full-time DEA agent, Camille Colon made some crucial introductions for me and shared some important recollections. Thanks also to Robert Cook, of the Office of The Special Narcotics Prosecutor in New York City, and retired DEA agent Robert Russello.

Among the retired FBI agents, a big tip of the hat to Bruce Mouw, who patiently shared his time in giving me crucial perspective about the Gotti years and access to public-record photographs. Former agents, Pat Colgan, Andris Kurins, Dan McCormick, and Joe OBrien were helpful in sharing their recollections of the events in the run-up to the arrests of Paul Castellano and John J. Gotti. Another retired agent, Phil Scala, worked with Mouw and the others on the Gotti investigation and shared his recollections about the Gambino family and the events surrounding Sammy Gravanos decision to become a cooperating witness.

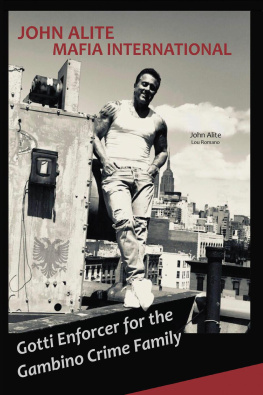

Former federal prosecutor Robert La Russo and retired defense attorney Joel Winograd had recollections of people and events described in Gottis Boys, which they readily shared. Steadfast Bronx defense attorney Murray Richman, Andrea Giovino, and John Alite also shared information.

Since the May 1982 crash of a Learjet off the coast of Georgia, which killed Salvatore Ruggiero and his wife, played a role in getting this story going, I have to thank people who were familiar with the accident and the recovery operations. There is of course captain Judy Helmey who spent hours looking through her old records and composing emails for me that described the incident and how close her father, Cpt. Sherman Helmey, came to dying himself that day. She also told me everything I need to know about barracuda! Bill Walsh, who did the first dive to the crash site provided vivid details of the wreckage and the discovery of human remains. Edward Crittenden, whose late father was involved in the recovery of the aircraft debris, also had useful descriptions of the events.

As is always the case, I relied on the published work of a number of fellow journalists and writers: Michael Arena, Marilyn Berkery, David Bird, William G. Blair, Ralph Blumenthal, Pete Bowles, Leonard Buder, Jerry Capeci, Maurice Carroll, Betty Darby, Walter Fee, Richard C. Firstman, Joseph P. Fried, Alan Feuer, Sean Gardiner, Robert W. Greene, Chris Hedges, Marvine Howe, George James, Peter Kerr, Don Lowery, Arnold H. Lubasch, Lawrence C. Levy, Mike McAlary, Gerald McKelvey, Robert D. McFadden, Lisa Morris, Alexandra K. Mosca, Nicholas Pileggi, Julia Preston, Selwyn Raab, Willliam M. Reilly, Tom Renner, Anthony Scaduto, Gale Scott, Alessandra Stanley, Ronald D. Smothers, Ronald Sullivan, Peg Tyre, Steve Wick.

At Newsday, assistant managing editor Mary Ann Skinner, Laura Mann of the newspapers library, and my news editor Monica Quintanilla again get my thanks for their help.

Gary Goldstein, my editor at Kensington, and my agent Jill Marsal, as they always do, did much to help bring this book to fruition.

EPILOGUE

J OHN G OTTIS FINAL IMPRISONMENT in the high-security facility in Marion, Illinois, effectively eviscerated his ability to run the Gambino family in any meaningful way. He had to rely on various surrogateshis brother Peter and his son Johnto hold the power as street bosses. That worked to some degree. Each of those two men would in turn be hobbled by separate federal prosecutions and terms of imprisonment. While his brother, son, and a few lawyers were able to visit him in prison and carry messages, Gottis ability to control what was happening on the street was diminished. When he went through the prison gates at Marion, Gotti was effectively handcuffed and stayed that way until his death behind bars in a prison hospital bed from the effects of throat cancer on June 10, 2002.

During the period after Gottis conviction, his son John as caretaker suspected that there were plenty of people cheating the crime family. This increased the tension between Junior Gotti and some others in the borgata. Juniors friend and fellow mobster Michael DiLeonardo, testified in a Brooklyn federal court proceeding in a case against Charles Carneglia that the younger Gotti suspected two other family members, Daniel Marino and John Johnny G Gammarano, were stealing construction racket funds and called both men to a meeting at a house in Brooklyn. According to DiLeonardo, Junior Gotti had two other armed family membersCharles Carneglia and Tommy Sneakers Cacciapoli hiding out in the house in case things went bad.

Joe Watts happened to accompany both Marino and Gammarano to the meeting and told Junior Gotti in no uncertain terms that his father had given him carte blanche to deal with the construction money, testified DiLeonardo. Junior Gotti respected what Watts told him and there was no trouble but, according to DiLeonardo, when Carneglia and Cacciapoli entered the room Watts sensed the bloodshed that had been in the offing and told Junior of the rashness of what he had planned.

In another display of dislike toward Junior Gotti, Gambino associate John Alite testified later that John Carneglia once railed against the younger Gotti, calling him a spoiled-brat motherfucker who he would have killed if it wasnt for his father. Incidents such as the Watts confrontation and the outburst by John Carneglia showed that Junior Gotti wasnt the diplomat in the mob world who garnered universal respect.

While his reign as Gambino official crime boss was about seventeen years, Senior Gotti only had about six years unfettered time on the street as boss before he was arrested in December 1990. His public persona, of course, persisted. He was the flashy don who reveled in all the publicity he received from an accommodating news media. When he was convicted in 1992, hundreds rioted outside the federal court in Brooklyn, overturning government cars. When he died, crowds of thousands lined the streets of Queens as Gottis funeral procession wound its way to his final resting place at St. John Cemetery. It was as if a rock star had passed away and some of the adulation from the public appeared quite genuine. News organizations sent up helicopters and hired motorcycles to follow the processions through Queens. All of this was shown as a coda in the 2018 film Gotti, although it didnt do anything to impress the critics.