Acknowledgments

These books about the old Mafia bosses tend to be modern archeological projects in that most of the people who were their contemporaries are long gone. That forces a writer to dig deep into the past, culling previously written materials, film clips, and official documents, as well as interviewing people who may have secondhand or thirdhand information about the subject. The job had the complication in the spring of 2020 of the coronavirus pandemic, which shut down a number of public research facilities. In the case of Vito Anthony Genovese, there were a number of people who helped me along the way and whom I want to acknowledge.

Fellow author Nick Pileggi, who has been a mentor by encouraging me on a number of book projects, provided me access to a rare copy of Dom Frascas early biography on Genovese, titled King of Crime . Nick also was, as he has always been, a font of information about the formative years of the Mafia, particularly the 1940s and 1950s. We talked for hours, even while Nick was in the middle of working on the film The Irishman .

In Italy, author and Italian cuisine expert Rossano Del Zio worked tirelessly over many hours to translate parliamentary reports and other materials for me, which helped round out the story of narcotics dealing during the 1950s.

In law enforcement, NYPD Chief Thomas Conforti helped provide access to old records about some of the characters in the Genovese story.

Retired Drug Enforcement Administration official James Hunt, whose father was involved in the 1958 investigation of Genovese, provided recollections about his fathers activities. Allison Guer-riero also gets my thanks for recommending that I talk with Hunt.

Relatives of Genovese who provided information and merit my thanks are his grandson Philip Genovese Jr., as well as two people who are related distantly to Genovese: Kate Harmon Gmehlin and Frank Esposito.

Employees of the National Archives and Records Administration provided key reference help: Kevin Reilly (New York City), Carey Stuum (New York City), and Tom McAnear (College Park, Maryland).

Colleague John Doyle gets thanks for his enthusiasm and encouragement, while Ida Van Lindt provided some materials from the files of her late boss, Manhattan District Attorney Robert Morgenthau, who for a time served as Manhattan U.S. Attorney in the 1960s.

At Newsday , Laura Mann once again helped get me access to old photographs, while my editor, Monica Quintanilla, also provided assistance in my scheduling time off.

Thanks again to Gary Goldstein, my editor at Kensington, for guiding this book to fruition. My agent, Jill Marsal, gets my appreciation for handling the business side of this project.

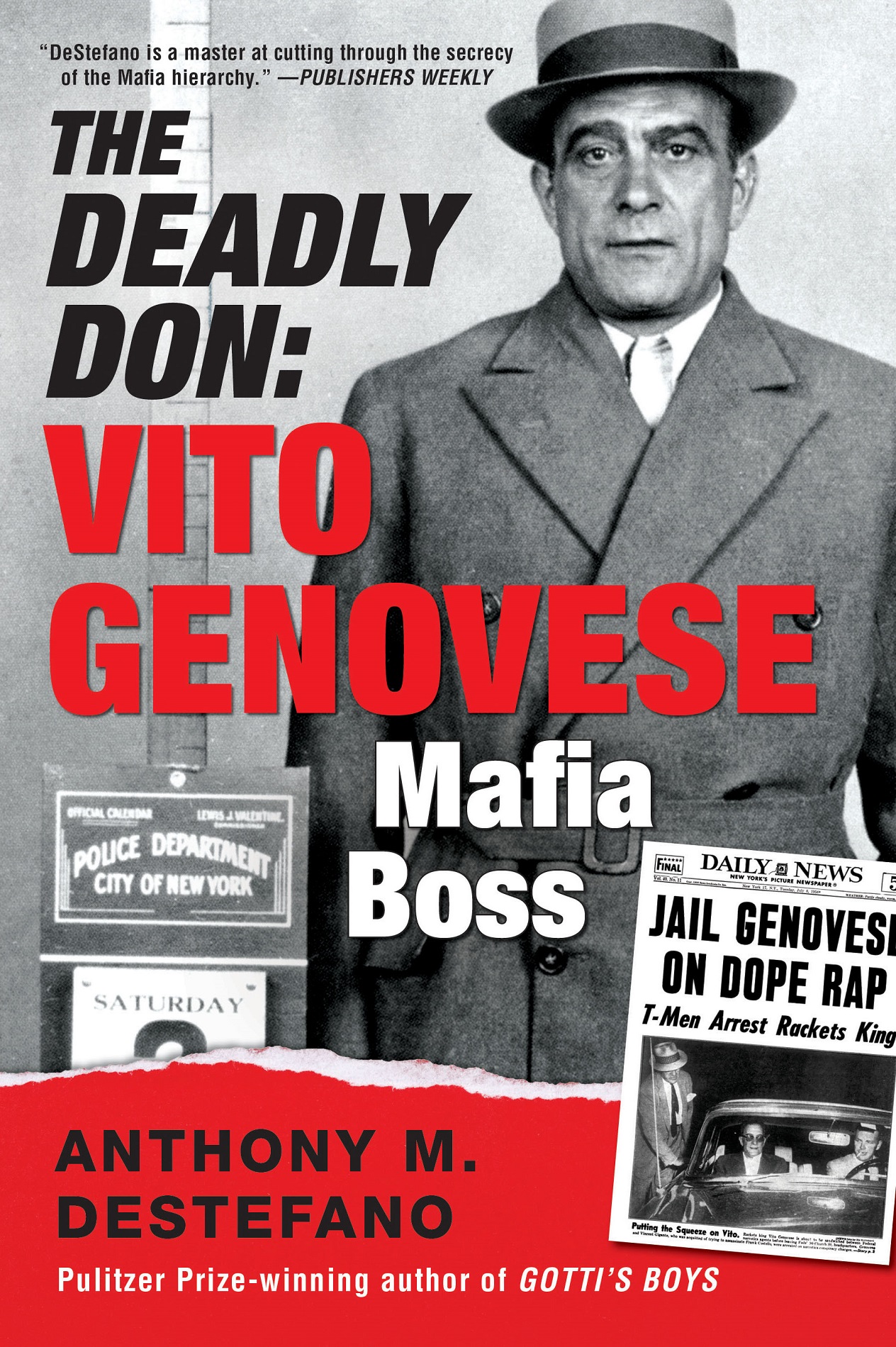

Also by A NTHONY M. D ESTEFANO

GOTTIS BOYS

The Mafia Crew

Who Killed for John Gotti

TOP HOODLUM:

Frank Costello, Prime Minister

of the Mafia

THE BIG HEIST:

The Real Story of the Lufthansa Heist,

the Mafia, and Murder

MOB KILLER:

The Bloody Rampage of Charles Carneglia,

Mafia Hit Man

KING OF THE GODFATHERS:

Joseph Massino and the Fall of

the Bonanno Crime Family

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Journalist A NTHONY M. D E S TEFANO has covered organized crime for over four decades, including the crime beat for New York Newsday for the past thirty years. He was a member of a New York Newsday team of reporters who won the 1992 Pulitzer Prize for spot news coverage of a New York City subway crash. His bestselling books include Gangland New York , King of the Godfathers , Mob Killer , and Vinny Gorgeous , among others.

Epilogue

I N HIS LIFETIME, V ITO G ENOVESE USED his cunning, guile, and canny sense of Mafia politics to cement his rise to the top. In the days after World War Two and the Korean War, if there ever was a boss of all the bosses, Genovese was seen as the man to fit the bill. Until his conviction on the heroin case in 1959, he was lucky enough to escape the long arm of the law, particularly as the other bosses found themselves beleaguered by the federal governments efforts to tie them into the big Apalachin conspiracy, a classic case of overreach by prosecutors that ended in a stinging reversal of the convictions.

But as The Deadly Don detailed, Genovese made some costly strategic decisions about planning to hold the meeting in Apalachin that led to a disaster of bad publicity and seemingly never-ending investigations. Some have theorized and even outright stated that Genoveses mistakes angered others in the Mafia who then set him up to fail with Apalachin and in the drug cases. The case for the latter is advanced by Chuck Giancana, the half brother of legendary Chicago mob boss Sam Giancana, and Chucks nephew Sam in their 1993 book Double Cross: The Explosive Inside Story of the Mobster Who Controlled America .

The Giancana book made numerous claims that the elder Giancana had ties to the CIA and had a hand in ordering the deaths of President John F. Kennedy and Marilyn Monroe, as well as a host of other crimes. But deep in the book, the authors related a conversation between two Chicago gangsters in which they discussed how Nelson Cantellops was being used to set up Genovese in the big heroin case. Cantellops, according to a man identified only as Willie, was used by Giancana to set up Genovese. Cantellops was supposedly a soldier of Willies and was used by Giancana as a sap to screw Genovese with the help of some other Mob big shots. Giancanas motive was to get Genovese out of the picture because he was seen as the only Mafia boss who would stand up to the grasping power of the Chicago Mafia, or so it seemed.

Since [Giancana] supplied the plan and the manpower, Lansky, Gambino, Costello and Luciano supplied the dollars to finance the narcotics caper that would ultimately frame Genovese.... The plan worked perfectly; Genovese was arrested, thanks to Cantellopss testimony, and sentenced to fifteen years in prison, the Giancanas alleged in their book.

There is a kernel of known truth to that Giancana story, at least in terms of Cantellopss travels. Cantellops did spend some time in Chicago when he came to the States, but it was for a very short period, for a few days, he said, working in a restaurant before he left for New York. If that is the case, it is improbable that he did enough in his life as an itinerant petty criminal that he could be considered a soldier in any Chicago crime group. More to the point, Costello had an aversion to drug dealing, wanted respectability, and was already being watched closely by the federal government. Besides, Costello had already retired from mob life after the assassination attempt on him. All of which meant that Costello likely wouldnt have been involved in financing heroin deals.

Lansky was too smart an operator, with too many dealings in Cuba and Florida, to do risky drug financing, although the FBN deemed him to be someone involved in the past with financing narcotics transactions. Gambino was also viewed by the FBN as a Mafioso who had done drug financing, and Luciano was also seen in the same light, operating from his base in Italy. But the authors of Double Cross cite nothing but their own claims about conversations with people who died long ago as proof for the Genovese set-up. In addition, when it came time to prosecute the Genovese case, prosecutors charged garment businessman Benjamin Levine as the chief financier of the various heroin buys done by the conspirators.