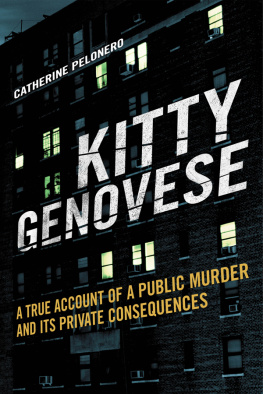

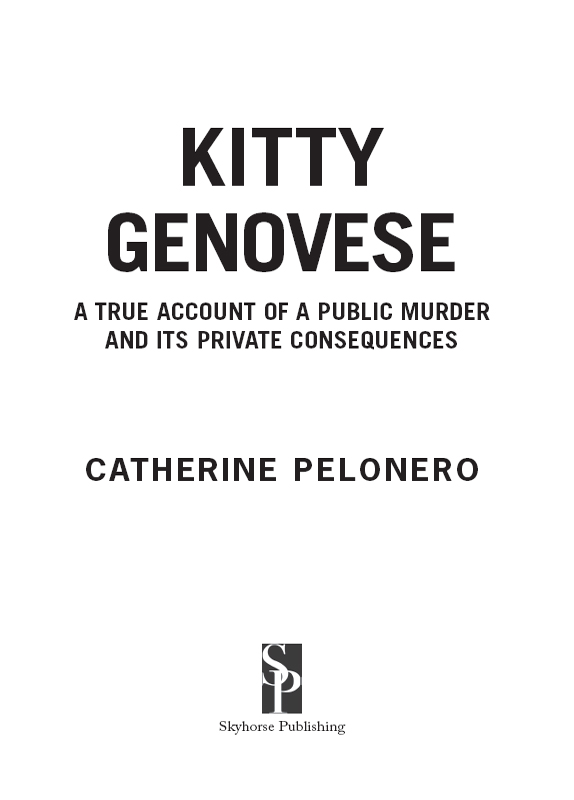

Copyright 2014 Catherine Pelonero

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-62873-706-6

Printed in the United States of America

NOTE TO THE READER

THE RE-CREATION OF events in this true story was at all times done as accurately as possible, drawn from a wide variety of sources that were corroborated and cross-referenced to whatever extent possible. A list of sources and references is included at the end of the book.

In a few instances, pseudonyms have been used to preserve privacy. Some names, mainly those of surviving assault victims and certain others whose identities are not central to the story told here, have purposely been omitted.

FOR MY FRIEND, JOE DE MAY

MY MOTHER, TRIEVA PELONERO

AND MY HUSBAND, JOSH BREWSTER

WITH MY LOVE AND GRATITUDE

Covered with ashes, tearing my hair, my face scored by clawing, but with piercing eyes, I stand before all humanity recapitulating my shames without losing sight of the effect I am producing, and saying: I was the lowest of the low. Then imperceptibly I pass from the I to the we.... I am like them, to be sure; we are in the soup together.

The Fall by Albert Camus

INTRODUCTION

IT WAS THE location, many later said, that gave a heightened sense of horror to what happened. Kew Gardens was not the type of place where anyone expected prolonged screams to shatter the middle-class serenity. It was not a neighborhood where anyone expected to find bloodstains on the sidewalk or bloody handprints on storefront windows, a macabre trail to the site of an unspeakably violent end.

Kew Gardens is in Queens, a borough of New York City that sits east of Manhattan and connects to it via bridges and tunnels. Queens is bordered by the waters of Long Island Sound on the north and Jamaica Bay to the south, and eastward lies the aptly named Long Island, a lengthy expanse of towns and villages that eventually shrinks to its end at the Atlantic Ocean.

Queens had steadily gained residents throughout the 1950s and into the next decade as the populations in Manhattan, Brooklyn, and the Bronx continued to decline. By 1964, Queens was not only the largest borough in land area at more than four times the size of Manhattan, but also had a population in excess of 1.8 million. Yet in spite of its prominence in size and populace, and the fact that Queens had been chosen as the site of the upcoming 1964 Worlds Fair, the New York Times did not have a full-time reporter assigned there.

Queens had little to offer in terms of news value. It was simply a place where ordinary people lived unremarkable lives, officially part of New York City but actually a collection of distinct communities that operated somewhat like independent towns rather than neighborhoods in the nations most prominent urban behemoth. Of course, the very factors that made it unappealing to a major news outlet had the opposite effect on regular people in search of a nice place to call home.

Kew Gardens was one of the jewels of the borough: an upscale neighborhood with low crime, gracious apartment buildings on its main streets, and impressive single-family homesincluding several early twentieth century mansionsresting in classic splendor on its tree-lined side streets. In March of 1964, only four months after the assassination of President Kennedy, with crime on the rise and the tensions of the Civil Rights Movement threatening to erupt, Kew Gardens evoked a sheltered stability; a community still softly aglow with staid and demure charm, almost a rebuke to the rapid changes and sense of uncertainty ushered in with the new decade. Kew Gardens looked and felt like a good neighborhood with a slower pace, almost a throwback to a gentler timeone of the few such areas left for the middle class in New York City. It was the kind of place where people aspired to live.

This perception of safety and decency explains, in part, why a single murder on a cold winter night sparked a cataclysm in a city that had over five hundred homicides in the prior year. The where escalated the shock, but the reports of what was doneand not donewhile the blood flowed and the screams echoed transformed another urban tragedy into a globally publicized gasp of horror. The chain of events, told and retold in various abridged versions in streams of front-page headlines and magazine articles, on television and radio, and eventually even in folk songs and plays, quickly came to symbolize not only the worst in human natureand most distressingly, the apparent moral vacancy to be found in regular good peoplebut also became the launching pad for a new field of psychological study.

As for the community at the focal point, the collective cry of outrage rained down upon it with the sudden ferocity of a flash hurricane, catching them unprepared, unguarded, scrambling for shelter in wide-eyed disbelief, and further finding themselves trapped in a storm of pelting criticism that abated but never completely ceased, rising and ebbing like the piercing wail of the trains that thundered through its center day and night, year after year.

The questions arose, publicly and repeatedly. How could this terrible thing have happened? When had this awful change in society come about? Why did decent people stand by doing nothing as an atrocity played out in front of them?

Experts in human behavior were at a loss to explain. So began a clinical quest for answers. Scholars and psychologists embarked on years-long studies with alchemistic zeal, stirring great cauldrons of research and experiments in an attempt to conjure the key to this strange, seemingly new phenomenon.

Gradually, an image took shape: But the observers found themselves staring at something that looked less like a phenomenon and more like the reflection of a mirror. The specter that emerged resembled not a black-and-white portrait of uncommon evil, but a kaleidoscope of human instincts and reflexes, prejudices and fears, callousness and cruelty; startling not because they were foreign, but so familiar.

PART ONE

FEAR OF THE STRANGER

I was seven years old when it happened. There was a patch of grass in the rear of the buildings alongside the train tracks where we would play ball and a big bush where numerous intercepted catches and foul balls ended up. For years afterward, no kid wanted to fetch a ball that had found its way into that bush. We knew there was a murdered girl in there. She hadI have no idea where we got this number from but we all knew it38 wounds in her body. She was waiting there to get us. We used to ask why. The answers varied between, Thats a long story, and Because you didnt save her...

Of course, the fact that it happened in this idyllic neighborhood had a lot to do with it. If it had happened in the South Bronx, I dont think it wouldve even made page 15 of the Daily News.