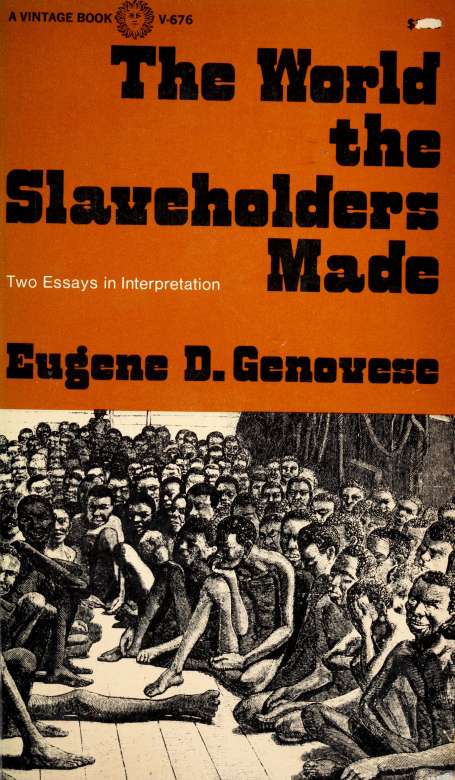

Eugene D. Genovese - The World the Slaveholders Made: Two Essays

Here you can read online Eugene D. Genovese - The World the Slaveholders Made: Two Essays full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1971, publisher: Random House, genre: History / Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The World the Slaveholders Made: Two Essays

- Author:

- Publisher:Random House

- Genre:

- Year:1971

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The World the Slaveholders Made: Two Essays: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The World the Slaveholders Made: Two Essays" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The World the Slaveholders Made: Two Essays — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The World the Slaveholders Made: Two Essays" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

This book made available by the Internet Archive.

Xra]?odi2LC&iora

This book tries to do three complementary things: to extend an analysis of the society of the slave South presented earlier; to contribute to a rapidly unfolding discussion of the comparative study of modern slave societies; and to offer some suggestions for the development of the Marxian interpretation of history.

In 1965, I published a book of essays, The Political Economy of Shivery, which advanced a point of view toward the nature of the society of the slave South, and made the mistake of promising a number of supporting studies "soon/' The promise was made in good faith, for those studies were indeed well along. One, a study of George Fitzhugh and the logical outcome of the slaveholders' philosophy, was then about finished and is included as the second essay in this book; the other, a study of the black slave, somehow gets bigger and more complicated and has yet to be finished. Part of the delay has been occasioned by the reception of unusually high-level and constructive criticism from many friends and colleagues: the cogency of their arguments, suggestions, objections, and questions has forced me to go slow.

The serious criticism of my earlier work primarily con

Introduction

cerned the failure to array sufficient evidence in support of the theses on the slaveholding class and its regime and the failure to'relate that regime to the other slaveholding regimes of the New World. I accept the criticisms in principle and offer the present book as a first installment on an extended reply. These essays try to do somethingnot nearly enough toward meeting the first criticism and much more toward meeting the second. No one who remained unconvinced by the argument of The Political Economy of Slavery is likely to be convinced by this extension, but even the brief discussion of the society of the slave South in the first essay has provided the occasion for a better balanced statement than appeared earlier. The thesis that an essentially prebourgeois ruling class dominated the South has been modified in the light of criticism. It was never intended to deny the hybrid nature of the class or the society, and the earlier book does contain explicit statements to that effect. Nevertheless, zeal to stress the side that was the less appreciated and yet the more important apparently led to a one-sided impression, which a brief general restatement in the first essay and a fuller discussion in the second may begin to correct. No slave society in modern times could free itself totally from the economic, social, and moral influence of modern capitalism; the problem of evaluation must center on the extent to which slavery threw up countervailing forces and the extent to which those forces prevailed over an omnipresent rival buried deep within its economy and ideology and simultaneously confronting it from without. These essays, hopefully, will also correct the maddening and oft-repeated insistence of even the most careful scholars that I characterized the slave South as "feudal." How and where such an idea arose is a mystery to me, but at least this book should end that misunderstanding.

The first essay attempts to provide a framework within which the New World experience with slavery may be studied comparatively and linked to the history of Western Europe, as well as Africa. It aims to replace the current

INTRODUCTION

vii

viewpoints, which take the race question as their point of departure, with an alternative, which takes the formation and development of social classes as its point of departure. As such it has a double purpose: to advance the discussion of the comparative history of slavery, and to defend the claims for the superiority of the Marxian interpretation of history. Despite rapid and impressive strides, the comparative history of slavery seems to me in danger of bogging down, for the various interpretations currently informing the discussion are proving unable to solve any of the vital questions concerning the place of slavery in the socioeconomic evolution of the Western world, or even to solve the two major questions to which they have been specifically addressedthe several paths to abolition and the patterns of race relations. The question of abolition has been made a test case by the participants in the debate themselves and ought to be welcomed as such by Marxists, for the special strength of Marxism resides in its usefulness as an explanation of transitions from one social system to another. For reasons that this essay will try to make clear along the way, the patterns of race relations must be treated as a series of special cases within a wider historical process propelled essentially by class forces.

My hopes for offering something useful toward the development of a Marxian interpretation of history rest on an attempt, made explicit in a general way in Chapter 1 of the first essay and left implicit throughout the book, to transcend the narrowly economic notion of class and come to terms with the "base-superstructure" problem that has plagued Marxism since its inception. Marxists have tended to let themselves be suspended between the assertion of the primacy of "material" forces and the necessity to recognize that ideas, once called into being and rooted in important social groups, have a life of their own. In recent decades general theoretical and philosophical contributions, especially those of Mao Tse-tung and Antonio Gramsci, have pointed to a way out of the traps implied in the juxtaposition of these viewpoints. There is, however, a limit beyond which general

yiii

Introduction

theoretical analysis cannot take us. The quality of the contributions of Mao and Gramsci themselves demonstrates as much, for the advances their work has encouraged would have been impossible without their careful, empirically based treatments of such special questions as the class structure of the Chinese countryside or the place of the Mezzogiorno in the Italian Risorgimento. The most important work being done today is to be found in particular historical investigations, rather than in grand theoretical pronouncements; to the extent that the latter have been forthcoming as serious efforts at synthesis, in contradistinction to dogmatic assertions, they have come out of hard digging in the sources and out of attempts to pay respectful attention to the ideas of major ideological opponents within and without the historical profession. The scholarly work of such exemplary Marxist historians as Christopher Hill, Eric J. Hobsbawm, and E. P. Thompsonto name only three prominent Englishmen who are primarily concerned with their own country in a world perspectivehas contributed, in my opinion, immeasurably more toward the development of a Marxian interpretation than have countless volumes on "dialectical and historical materialism/' One need not have illusions about matching their extraordinary talent to be willing to work in their spirit.

Specifically, many years of grappling with the problem of the historical character of the Southern master class have convinced me that it cannot be understood apart from its relationship to slaves and nonslaveholding whites, that those other classes cannot be understood apart from a consideration of the quality and the mechanisms of ruling-class hegemony, and that none of these classes can be understood without an appreciation of the uniqueness and particularity of every social class. Chapter i of the first essay tries to work out some of these ideas in a rough and tentative way. The remainder of the book tries to work out some of the ramifications.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

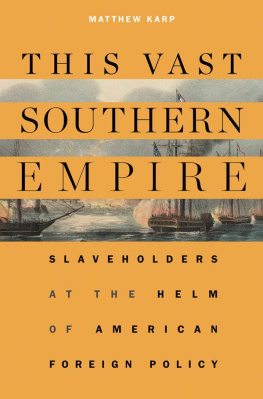

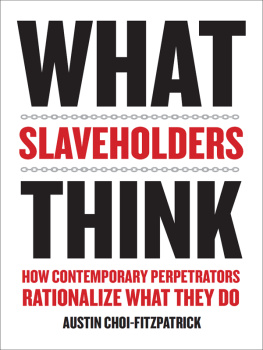

Similar books «The World the Slaveholders Made: Two Essays»

Look at similar books to The World the Slaveholders Made: Two Essays. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The World the Slaveholders Made: Two Essays and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.