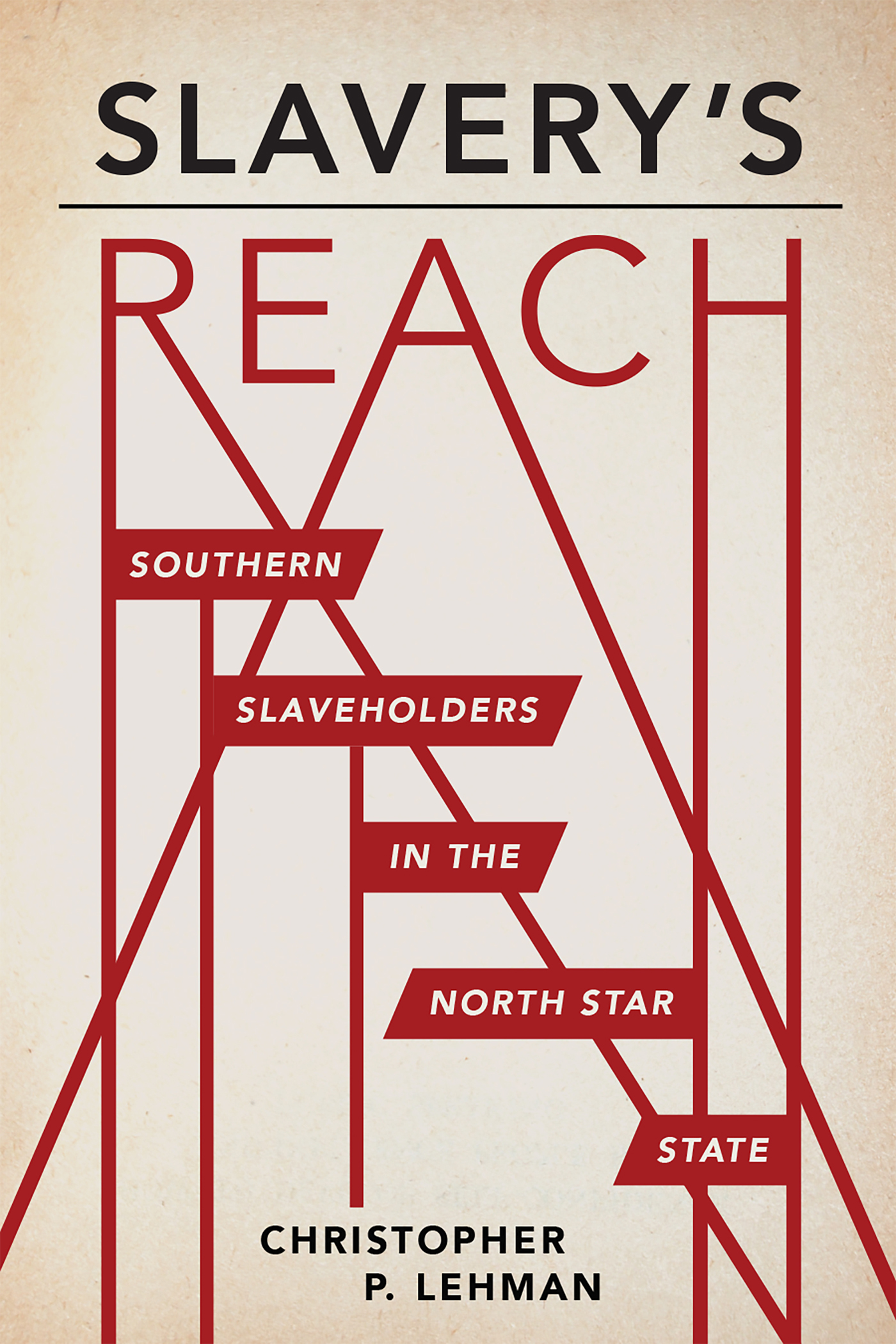

Slaverys Reach

Slaverys Reach

Southern Slaveholders in the North Star State

CHRISTOPHER P. LEHMAN

Text copyright 2019 by Christopher P. Lehman. Other materials copyright 2019 by the Minnesota Historical Society. Unless otherwise indicated, photos are from MNHS Collections. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, write to the Minnesota Historical Society Press, 345 Kellogg Blvd. W., St. Paul, MN 551021906.

mnhspress.org

The Minnesota Historical Society Press is a member of the Association of University Presses.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

International Standard Book Number

ISBN: 978-1-68134-135-4 (paper)

ISBN: 978-1-68134-136-1 (e-book)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lehman, Christopher P., author.

Title: Slaverys reach : Southern slaveholders in the North Star State / Christopher Lehman.

Other titles: Southern slaveholders in the North Star State

Description: Saint Paul : Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: From the 1840s through the end of the Civil War, leading Minnesotans invited slaveholders and their wealth into the free territory and free state of Minnesota, enriching the areas communities and residents. Dozens of southern slaveholders and people raised in slaveholding families purchased land and backed Minnesota businesses. Slaveholders wealth was invested in some of the states most significant institutions and provided a financial foundation for several towns and counties. And the money generated by Minnesota investments flowed both ways, supporting some of the Souths largest plantations. Christopher Lehman has brought to light this hidden history of northern complicity in building slaveholder wealthProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019020093 | ISBN 9781681341354 (paperback) | ISBN 9781681341361 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: SlaveryMinnesotaHistory19th century. | SlaveryMinnesotaEconomic aspects. | InvestmentsMoral and ethical aspectsMinnesota. | SlaveholdersMinnesotaHistory19th century. | SlaveholdersSouthern StatesHistory19th century. | SlavesMinnesotaHistory. | BusinesspeopleMinnesotaHistory19th century. | SlaveholdersMinnesotaEconomic conditions. | MinnesotaEconomic conditions19th century.

Classification: LCC E445.M57 L44 2019 | DDC 306.3/6209776dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019020093

This and other Minnesota Historical Society Press books are available from popular e-book vendors.

Contents

Slaverys Reach

INTRODUCTION

Hidden in Plain Sight

M any communities throughout the southern United States are graced with visually stunning architectural artifacts of the nations era of legal slavery. These Greek Revival mansions with columned facades once were home to some of the countrys wealthiest slaveholders. Robert Caruthers, who held one hundred enslaved people, established his domicile in Lebanon, Tennessee. The palatial home of William Aiken, who held seven times the number of slaves as Caruthers, stands in Charleston, South Carolina. Fountain F. Beatties house, where he resided with his two dozen slaves, is in Greenville, South Carolina. Samuel Boydowner of a half dozen plantations throughout the Southlived in Natchez, Mississippi, where his mansion still stands.

These homes have special historical importance because they are rare surviving structures connecting slavery to Minnesota. The slaveholders who lived in these mansions spent tens of thousands of dollarsprofits made from slave laboron real estate in the northwestern territory and state.

The connections between Minnesota and slavery went beyond those made by distant, wealthy enslavers. A slaveholding financier provided much of the capital behind the fur trade in southern and central Minnesota. Military officers, federal appointees, commuting businessmen, small farmers, banks and insurance companies, hotelkeepers, and land speculators all brought connections to slaveholders wealth into Minnesota Territory. Some brought slaves, too.

Minnesota existed as a territory and a state during only the last sixteen of the nations 246 years of legal slavery, and it now has even fewer buildings that reflect its involvement in slavery than the South does. The hotels where slaves stayed with slaveholders burned down or were demolished over a century ago, and the summer homes that enslavers built met similar fates. The buildings have not survived to bear witness to the tremendous impact of wealth from slave labor on Minnesotas development in those sixteen years. And the choices of Minnesotans in remembering this history have done even more to minimize its significance.

William Aiken home, Charleston, SC, 1963. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

From the establishment of Minnesota as a territory in 1849 to the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution in 1865, slaveholders invested in land and businesses in Minnesota. Many of them traveled from their southern homes to make the transactions in person, but others arranged for Minnesotans with power of attorney to facilitate the purchases. The investors practices spanned the gamut of human possession, represented by yeomen who owned a single enslaved person, elite planters who kept hundreds of people captive, reluctant heirs who manumitted slaves whenever possible, and enthusiastic masters who acquired as many people as possible.

Rear view of Aiken home showing service building and stable on right, slave quarters on left, 1963. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

It is not surprising that southerners who were prosperous enough to invest or vacation in Minnesota relied on slaveholding wealth. This is not, however, the point. The recruiting of investors by Minnesotas political leaders, the eagerness of new communities to attract those investments, the participation of financial institutions, the catering to rich touristsall were part of the web of connections tying northern development to southern slavery. Indeed, wealth pouring into Minnesota from the northeastern United States was also made in banking and industries that grew because of the labor of enslaved people. Minnesotans and other northerners have forgotten their states complicity in the slaveholding economy, just as some southerners have denied that the Civil War was fought over slavery.

A reader might question the relative level of slaveholder investment in Minnesota land and businesses. Did it comprise one percent or ten percent or 40 percent of all investment in the state? While it is not possible to calculate this figure, it is abundantly clear that people in Minnesota invited, encouraged, and welcomed any investments and expenditures from slaveholdersand broke their own laws in order to facilitate such income. Investments made by slaveholders were crucial to Minnesotas development at times and in specific areas of the state. This book does not argue that slaveholder wealth was the defining element in the growth of the new territory. Instead it uncovers the ties and demonstrates how Minnesotans allowed illegal slaveholding in their communities and benefited from it. Minnesota was not a distant land, far from the turmoil of 1850s US politics. It was the front lines of the prewar battle over slavery. In tracing the people, financial institutions, and political entities that brought slaves and slaveholding wealth into the territory and state, this book demonstrates slaverys reach.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.