EARLY BIRD BOOKS

FRESH EBOOK DEALS, DELIVERED DAILY

BE THE FIRST TO KNOW

NEW DEALS HATCH EVERY DAY!

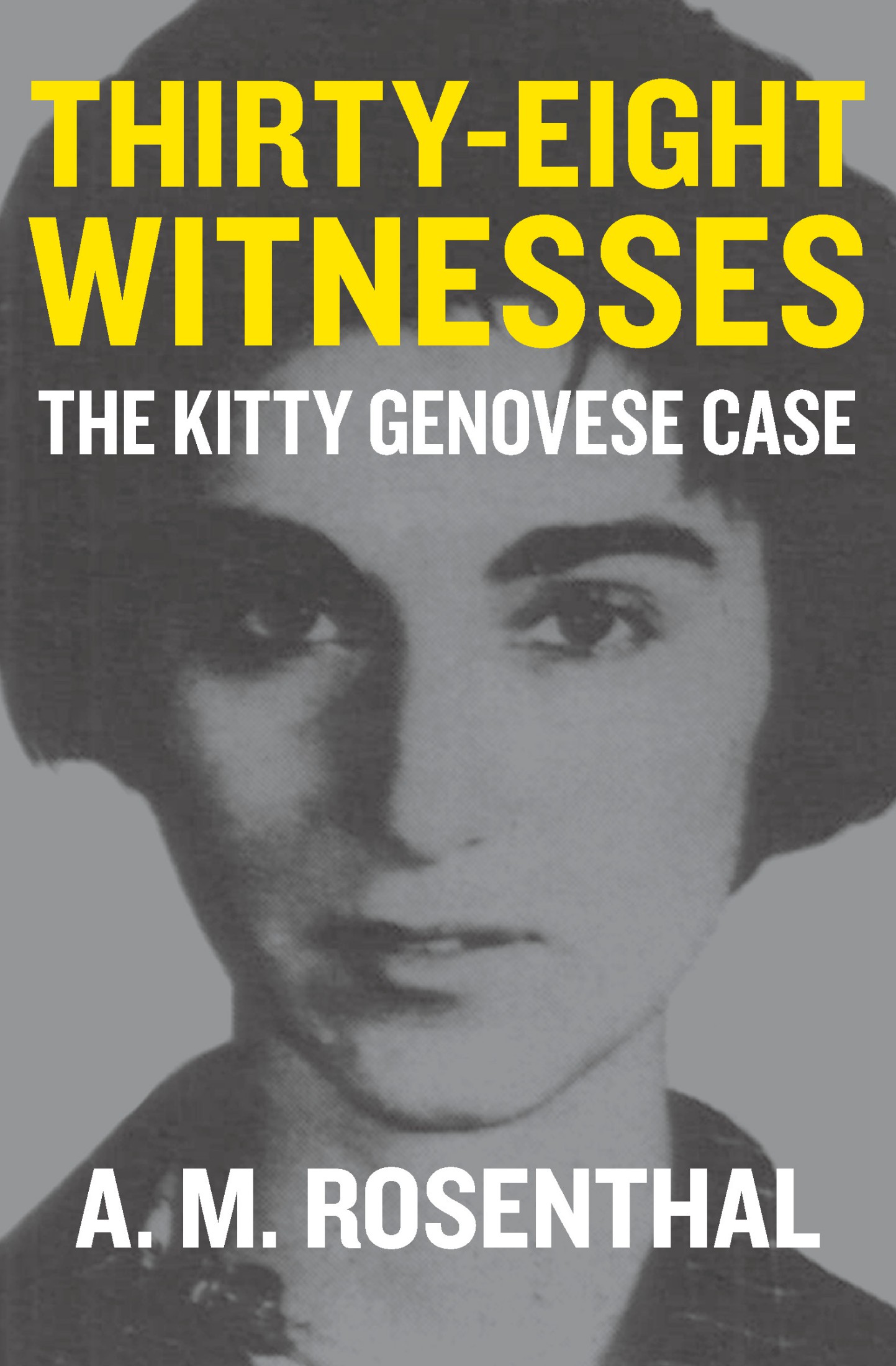

Thirty-Eight Witnesses

The Kitty Genovese Case

A. M. Rosenthal

PREFACE BY SAMUEL G. FREEDMAN

When A. M. Rosenthal died in May 2006 at the age of eighty-four, he left behind a career as notable for one striking gap as for its innumerable achievements. His journalistic record included winning a Pulitzer Prize for his reporting from Poland, defying the Nixon Administration to publish the Pentagon Papers, serving seventeen years as the executive editor of the New York Times, and, even after nominal retirement, writing opinion columns for both the Times and the Daily News. He produced one of the most significant ruminations on the Holocaust in his 1958 article, No News From Auschwitz, and in later years he championed human-rights issues from religious freedom in China to female circumcision in Africa.

Yet Abe Rosenthal, as everyone in his wake knew him, never wrote the book one might well have expected from a journalist of his caliber. He never wrote sweeping narrative non-fiction in the manner of Gay Talese, David Halberstam, and J. Anthony Lukas, among his younger colleagues on his Times. He never wrote an autobiography, as did Arthur Gelb and Max Frankel, his partner and successor, respectively, in the Times hierarchy. He never wrote a family history, as did Joseph Lelyveld, another executive editor, even though the events of Rosenthals childhood had tragedy on a Dickensian scale.

Like certain great reporters and editors, perhaps most, Abe operated on the biorhythms of the daily deadline. He was too restless, too driven, too curious to step off the treadmill for very long. As intelligent as he was, he fundamentally went with his instincts, and he wore his emotions flagrantly. He lacked the patience and maybe the introspection to pull back from the hurly-burly of human events long enough to grasp and render them in book form.

If you search a library catalogue for books written by Rosenthal, A. M., you will find only six or seven titles listed, and several of those are anthologies of work by Times writers with Rosenthal credited as editor. The only real books that Abe left are, appropriately enough, books that rose directly out of breaking news stories that he oversaw as city editor, stories that came to possess him. One of those books, One More Victim, co-written with Arthur Gelb, explored the pathology of Jewish self-hate through the life and death of a young man named Daniel Burros, who tried to hide his actual identity by reinventing himself as a Ku Klux Klansman and neo-Nazi. The other book is the one you hold here, Thirty-Eight Witnesses, the story behind the Kitty Genovese murder case. Originally published in 1964, it remains fearsomely relevant today, a testament both to Rosenthals genius and journalisms mission.

Even at the remove of more than forty years, the essential outlines of the crime remain familiar, an enduring part of our cultural vocabulary. Shortly after 3 A . M . on March 13, 1964, a twenty-eight-year-old woman named Catherine (Kitty) Genovese was returning from her job at a tavern to her apartment in the middle-class neighborhood of Kew Gardens, Queens, when she was attacked by a man wielding a knife. Over the course of thirty-five minutes, the assailant stabbed her in three separate rounds of assault. She screamed for help repeatedly. Only after Genovese lay dying, three doors from her apartment house, did any of her neighbors call the police.

A certain myth has grown up around Rosenthals coverage of the Genovese case. Like many myths, it contains both truths and falsehoods. In this version of events, which Rosenthal neither created nor disputed, he was alone in seizing upon the passivity and apathy of the neighbors as the most salient part of the crime. It is true that the Timess first article, a mere four paragraphs, said nothing about the neighbors other than that they were awakened by her screams. It is true that New Yorks tabloids, the Post and the Daily News, indulged in the tawdry sport of blaming the victim, caricaturing Genovese as a barmaid who was separated from her husband and ran with a fast crowd while living in a Bohemian section of Queens. But it is also true that the Herald Tribune began its first-day story this way: The neighbors had grandstand seats for the slaying of Kitty Genovese. And yet, when the pretty diminutive twenty-eight-year-old brunette called for help, she called in vain.

It is possible, though not probable, that Rosenthal never saw the Herald Tribunes account. Speaking from my own experience on the Times, even a generation later, the newspaper often suffered from an institutional arrogance that led it to disregard its competitors, to believe that news wasnt really news until it appeared in the Good Gray Lady. Whatever the reason, Rosenthal seems to have been unaware of the earlier article on March 23, 1964, when he and Arthur Gelb had lunch near City Hall with Police Commissioner Michael Joseph Murphy. During the meal, Murphy told them, That Queens story is something else. A moment later, he uttered what any journalist would call the telling detail: thirty-eight. Thirty-eight people had witnessed the attack on Genovese and none had called the police. No sooner did Rosenthal return to the Times office than he assigned a reporter, Martin Gansberg, to report the story of those people.

You cannot appreciate Rosenthals decision without appreciating the man. The New York Times, circa 1964, was a newspaper that traditionally had been overseen by Southern gentlemen, written by Ivy League alumni, and copy-edited by Roman Catholics. It was deeply estranged from, almost embarrassed by, the Jewish heritage of its ruling families, the Ochs and Sulzbergers. Some of the Jews who rose up the reporting ranks chose to anglicize their namesTopolsky becoming Topping, Shapiro becoming Shepard. The less compliant sort, such as Abe Rosenthal and the labor reporter Abe Raskin, were assigned bylines with initials (A. M., A. H.) to efface their ethnicity.

Abe Rosenthal had grown up in the working-class Bronx, the son of a housepainter who had snuck across the border from Canada. During Abes childhood, he lost four of his five sisters to illness and his father to an accident on the job. Abe himself, stricken with osteomyelitis, lost use of his legs for a year and was cured only as the charity patient of a hospital. His life, suffused with tragedy and want, gave lie to every nostalgic clich about Jewish immigration.

City College served as Abes ladder of upward mobility, fulfilling its renowned role as the poor mans Harvard. He was writing for the Times while still an undergraduate. And when he went on to cover the worldheading the Times bureaus in Japan, India, Poland, and the United Nationshe never lost his ingrained affinity for the everyday people of New York City. By every account, while he did not initially welcome being appointed metropolitan editor, he dove into the position with characteristic passion. Rosenthal wanted to touch the nerve of New York, Gay Talese put it in his classic portrait of the