Caitlin Rosenthal - Accounting for Slavery

Here you can read online Caitlin Rosenthal - Accounting for Slavery full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2018, publisher: Harvard University Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Accounting for Slavery

- Author:

- Publisher:Harvard University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2018

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Accounting for Slavery: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Accounting for Slavery" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Accounting for Slavery — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Accounting for Slavery" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Accounting for Slavery

MASTERS AND MANAGEMENT

Caitlin Rosenthal

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2018

Copyright 2018 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved

Cover Design: Tim Jones

Cover Images:

Background: Ledger book from the Eli J. Capell Family Papers Collection, courtesy of Louisiana State University.

Inset: Picking cotton near Montgomery, Alabama, c 1860, by J. H. Lakin, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

978-0-674-97209-4 (hardcover : alk. paper) 978-0-674-98857-6 (EPUB)

978-0-674-98858-3 (MOBI)

978-0-674-98859-0 (PDF)

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows: Names: Rosenthal, Caitlin, author.

Title: Accounting for slavery : masters and management / Caitlin Rosenthal.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : Harvard University Press, 2018. |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017058060

Subjects: LCSH: SlaveryEconomic aspectsUnited StatesHistory18th century. | SlaveryEconomic aspectsUnited StatesHistory19th century. | SlaveryEconomic aspectsWest Indies, BritishHistory18th century. | SlaveryEconomic aspectsWest Indies, BritishHistory19th century. | Human capitalUnited StatesHistory. | Human capitalWest Indies, BritishHistory. | PlantationsUnited StatesAccountingHistory. | PlantationsWest Indies, BritishAccountingHistory. | Plantation ownersUnited StatesHistory. | Plantation ownersWest Indies, BritishHistory.

Classification: LCC HT905 .R67 2018 | DDC 331.11/734097309033dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017058060

For my parents, Jim and Cindy

Figures

Tables

When I began this project, I did not intend to write a book about slavery. I had just finished two years working as a management consultant with McKinsey & Company. It was a job I enjoyed. Every few months I found myself working at a different corporation on a different problem. There were always new industries, new ideas, and, of course, new data. I was just out of college, and as the most junior person on a teamthe business analystI often manipulated the spreadsheets of numbers that we relied on to help us make our recommendations.

Sometimes it felt a bit like alchemy: by simply combining a firms resources in new ways, we could help the company earn higher profits. And, as far as I could tell, it often worked. It did not seem to matter that I had not met most of the people represented in the data or that I barely grasped the technical details of the products. In fact, this distance gave me an advantage. Viewing a large division or even a whole company as an abstraction made it easier to lay out a strategy for profit. From basement conference rooms, twenty-two-year-olds calculated paths to increased efficiency, slicing and dicing data that might shape the lives of thousands of workers and many more customers.

I had the good luck to be there during a boom economy, so we were hiring, not firing; growing businesses, not cutting costs. And yet it sometimes made me uneasy. What did the models and numbers cover up? What stories was I missing by encountering production through a spreadsheet? When I started graduate school, I wanted to understand the history of this outlook and the scale that accompanied it. When did we begin to think about workers as cells in spreadsheets? What happens when businesses grow so big that they can only be comprehended quantitatively? How do labor relationships change when managers and owners encounter workers primarily as numberswhen CEOs are separated from thousands of workers by layers and layers of hierarchy?

During my first year of graduate school, I studied historical account books. I began my research where I assumed the story began, at least in America: in the New England textile factories and iron forges usually at the heart of the Industrial Revolution. The records I found advanced in fits and starts. Manufacturers sometimes kept time books and occasionally calculated output per worker, but their efforts were often thwarted when workers quit. Neat grids optimistically laid out to record data ended up partially blank or abandoned when workers left for new opportunities or to try their luck on a farm.

Around my second year of graduate school, the renowned economic historian Stan Engerman handed me a copy of Thomas Afflecks Plantation Record and Account Book. The volume blew me away. This was the most complex and comprehensive record book I had seen up till that point, and it included a detailed balance sheet as well as per-worker picking records. Further research would reveal that planters actually used these books very unevenly, with some of the same fits and starts of northern books. However, the most calculating slaveholders kept records as comprehensive as contemporary manufacturers. And Afflecks book was not the first or only example of sophisticated plantation accounting. As I followed leads from other scholars, I uncovered other remarkable sets of accounts, including detailed records for West Indian plantations, which were among the largest businesses of their time.

In the end, the direct ties between these plantations and todays data practices remain murky. This is not an origins story. I did not find a simple path where slaveholders paper spreadsheets evolved into Microsoft Excel. The narrative that emerged was far more complicated: many businesspeople in different geographies were developing new data practices independently. What I saw was a series of interconnected business histories that show how data practices often thought of as quintessentially modern coexisted with and even complemented slavery. Planters control over enslaved people made it easier for them to fit their slaves into neat numerical rows and columns. To borrow a twenty-first-century business buzzword, slavery and quantitative management were synergistic.

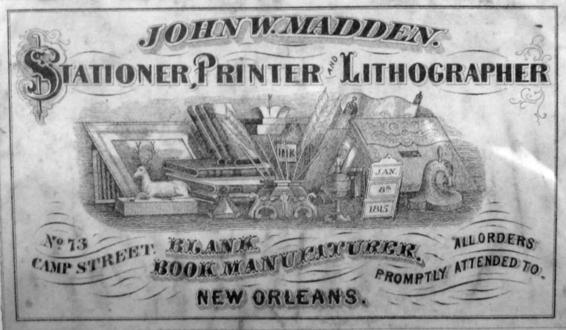

FIGURE P.1. The View from the Planters Desk.Book plates like this were sometimes pasted inside the opening cover of plantation account books. It offers a romantic view of southern business that elides the circumstances of production. John W. Madden: Stationer, Printer and Lithographer, New Orleans, Jan. 8, 1815. Bookseller label, Bookseller Collection, Box 2, Range 4, Station B. Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts.

Studying the ways profit and innovation can accompany violence and inequality is particularly important in the world of modern capitalism. The mythology of capitalism suggests that many individuals pursuing their own interests can make whole societies wealthier. In our current moment, it is a commonplace to hear people argue that the freer the market, the greater the profit and the faster the growth. Generally, those offering such explanations assume that a free market does not include slavery, but as I have conducted my research, I have come to see things differently. From the perspective of slaveholders and other free whites, the freedom to enslave was an economic freedom. They feared abolition because of the ways it would restrict their rights to control labor and property. Viewed in this light, the abolition of slavery was a triumph of market regulation that restricted their economic freedoms even as it offered freedom to so many others.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Accounting for Slavery»

Look at similar books to Accounting for Slavery. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Accounting for Slavery and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.