OUR SISTER REPUBLICS

OUR SISTER

REPUBLICS

The United States in an Age

of American Revolutions

CAITLIN FITZ

LIVERIGHT PUBLISHING CORPORATION

A DIVISION OF W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

INDEPENDENT PUBLISHERS SINCE 1923

NEW YORK LONDON

Copyright 2016 by Caitlin Fitz

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com

or 800-233-4830

Book design by Fearn Cutler de Vicq

Jacket design by Nicole Caputo

Jacket art: Simon Bolivar (1783-1830) and Francisco De Paula Santander (1792-1840) Traveling to Bogata with the Army of the 'Libertador' after the Victory of Boyaca, 10th August 1829 (oil on canvas), Francisco de Paula Alvarez (FL.1829) / Private Collection / Archives Charmet / Bridgeman Images; (Flags) The Stapleton Collection / Bridgeman Images

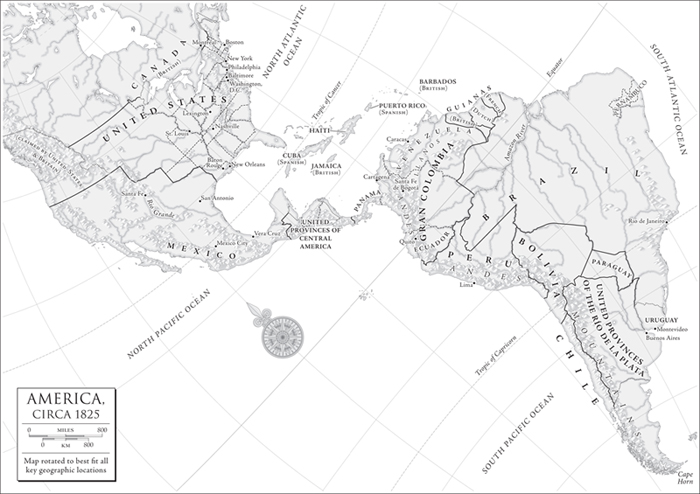

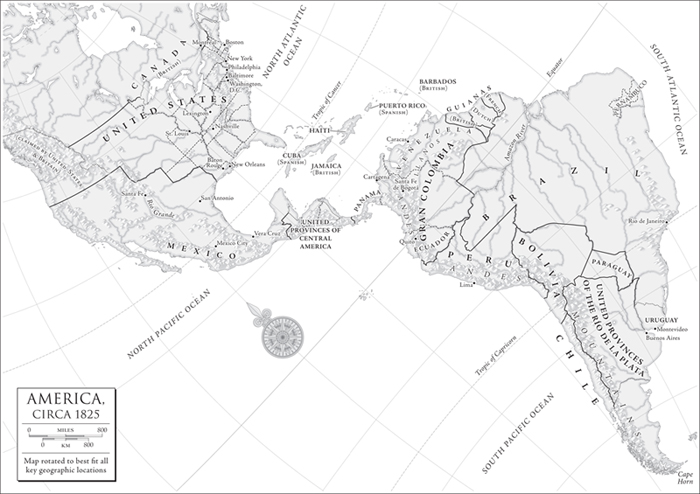

Map by David Lindroth Inc.

Production manager: Julia Druskin

ISBN 978-0-87140-735-1

ISBN 978-0-87140-765-8 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

To Ezra, my first friend.

CONTENTS

AN AGE OF

AMERICAN REVOLUTIONS

T HE HALF-CENTURY BETWEEN 1775 and 1825 was an age of American revolutions. In the United States, in Haiti, and throughout the entire Spanish-American mainland, insurgents declared independence and, improbably, obtained it, armed with tar and feathers, fire and farming implements, muskets and bloodstained bayonets. Brazil broke away too, brushing off a smattering of Portuguese forces in a single year. By the United States fiftieth birthday, most of the Western Hemisphere was independent from Europe, and almost all of the new nations had established republics, transforming subjects into citizens and breathlessly invoking equality, rights, even the pursuit of happiness. Every thing, in fifty years, has changed, and every thing is changing, a Kentucky congressman declared in 1822. It is the birth-day of a hemisphere redeemed, the jubilee of nations. A new order for the New World was emerging, or so it seemed to many who lived through the tumult.

From their earliest years of nationhood, U.S. audiences carefully monitored republican uprisings elsewhere in the world, proud in the belief that their own revolution had started such a magnificent trend. In reality, events south of the border owed more to specific developments within the French, Spanish, and Portuguese empires

This international enthusiasm ebbed and flowed with the Atlantic tides, but like the ocean, it was always there. It started strong in 1789, as the most storied monarchy in all of Europe started to succumb to cries for constitutional libert. U.S. onlookers exulted at news from France, thrilled to think that they had inspired such a powerful country to follow in their footsteps. Precariously fresh from their own nations revolution, clergymen bowed their heads and sang the blessings of French liberty; commoners donned tricolor cockades and sang La Marseillaise. Eventually, however, the excitement tapered. Federalists grew especially wary as Jacobin radicals took control in Paris; Republicans grew cautious as slaves in the French colony of Saint-Domingue took up arms against the islands slaveholding masters. In 1790, that tiny third of an island (now Haiti) was the wealthiest colony in the Americas, producing half of the worlds coffee and dripping, too, with the sweet juice of sugarcane and the sweat of those who planted and processed it. A year later and for the next thirteen years, it was dripping in blood,

By the early nineteenth century, therefore, doubt and disillusionment had tempered the early excitement. Even erstwhile Francophiles like Thomas Jefferson (who had stocked his homes with French furniture, French servants, French wine, and haute cuisine cooked by his enslaved, Paris-trained chef James Hemings) cringed as Napoleon Bonaparte, a self-proclaimed emperor who only pretended that his rule was constitutional or democratic, rose to power and occupied most of western Europe. Many U.S. onlookers felt like passengers aboard a political Noahs Ark, a lonely republic bobbing alone in a churning sea of monarchy and responsible for the fate of republicanism itself. [W]e now stand in a trying, a peculiar, and an isolated situation, one Philadelphia newspaper avowed. We are the only free government upon earth. America is left among the nations, a solitary republic. Some historians have even said that the United States was experiencing its own Thermidorian Reaction, its own turn away from the revolutionary radicalism of Paris and Port-au-Prince. Did not The American Revolution produce The French Revolution? an aging John Adams asked in 1811. And did not the French Revolution produce all the Calamities, and Desolations to the human Race and the whole Globe ever Since? I meant well however... I was borne by an irresistable Sense of Duty.

But just as Adams penned his lament, another set of revolutions was beginning to spread, and this time across far more of the globe than before. In 1810, demanding sweeping social change, some

Not even the listless equatorial doldrums could contain that kind of news. The trade winds and the westerlies swept it north into more temperate climes, and as they did, people throughout the United States erupted with joy, undeterred by the chaos in France and the tumult in Haiti. By the hundreds, they named their livestock, their towns, their sons, and sometimes even themselves after Spanish-speaking statesmen; by the thousands, they toasted hemispheric independence on every passing July Fourth. (And, in the first-ever episode of U.S. foreign aid, their representatives in Congress sent $50,000 worth of provisions to Caracas, for the use of the inhabitants who have suffered by the earthquake.) The excitement was sweepingit touched men and women, black and white, rich and poor, northerners and southerners and westerners. Most of those people took republicanisms southward spread as a compliment to themselves, seeing it as proof that their own ideals really were universal. The cause of Latin America became the cause of

The enthusiasm went beyond mere rhetoric, and beyond patchwork disaster reliefLatin American revolutionaries sought to ensure it. Over two hundred South Americans sailed to the United States in search of aid and asylum, many of them working to transform U.S. port cities into international hubs of the American independence wars. Encouraged by these revolutionary visitors, U.S. merchants sold boatloads of arms and ammunition to the rebels (and smaller amounts to royalists), while thousands risked their lives under rebel flags as mercenaries and privateers. All the while, rebel agents variously bribed and befriended newspaper editors in an effort to rally public opinion, convinced as they were that U.S. foreign policy took shape in the smoldering crucible of democratic politics and not simply in the private recesses of Washington. Sure enough, when the United States became the first nation in the world to recognize the independence of mainland Spanish America in 1822, people throughout the country exploded in celebration, a Noahs Ark no more.

Next page