Also by Michael J. Tougias:

For my mother, Diane Dodd, and for the families of Rudy Anderson and Chuck Maultsby.

For Jerry McIlmoyle and all the pilots who flew over Cuba during the Crisis. And to President John F. Kennedy for his steady hand and thoughtful deliberations.

O CTOBER 25, 1962

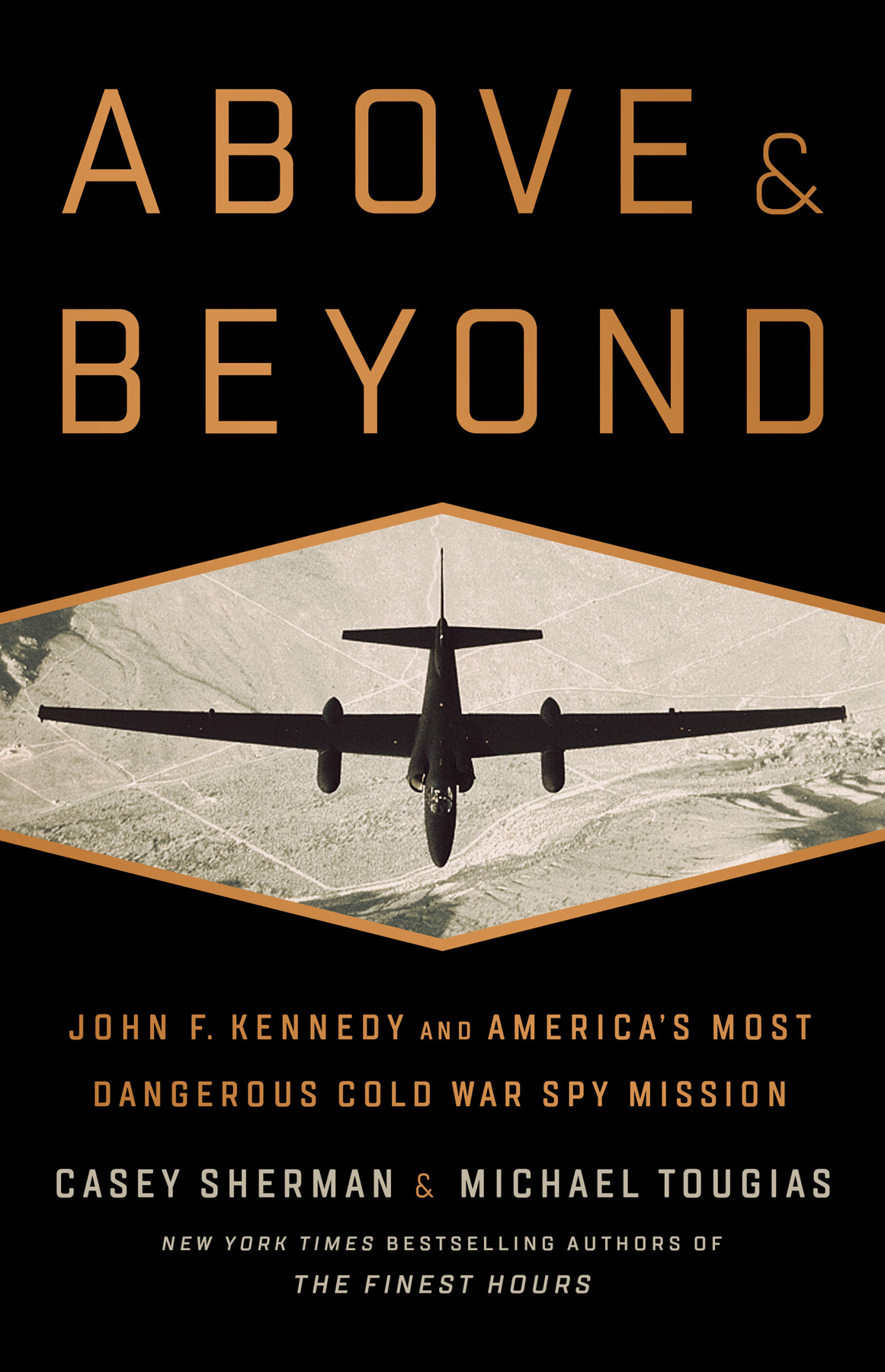

Captain Jerry McIlmoyle sat in the cramped cockpit of his U-2 spy plane on the runway at McCoy Air Force Base in Orlando, Florida. It was 10 a.m., and the sun was baking the tarmac, causing the thirty-two-year-old pilot to sweat inside his skintight pressure suit and fishbowl-size helmet. Beads of perspiration ran from his tightly cropped hairline down his forehead and into his bright blue eyes. Another U-2 pilot performed one last equipment check, including inspection of the hose running from the pressure suit to the oxygen supply that ran through the pilots emergency seat pack. This connection was of particular importance because Jerry would be flying at an altitude no other aircraft could reachan incredible thirteen miles above Earth. Should something go wrong and the cockpit lose pressure, the flight suit would inflate, providing Jerrys last line of defense against the dangerously thin air of the stratosphere. Without a pressurized cockpit or a functioning pressure suit, Jerrys blood would literally begin to boil, and death would soon follow.

Once the final flight check was completed and the canopy lid sealed, Jerry taxied toward the runways centerline. The wingspan on the superlight aircraft was so long103 feetpogo sticks were needed to keep each wing from nearly scraping the ground. Once at the centerline he engaged the brake and checked that the directional gyro read the same as the runways compass direction. He then ran the engine up to 80 percent of its maximum RPMs because anything higher would cause the aircraft to start sliding down the runway with its brake locked. Next he checked that all systems were in good operating order and then released the brake, advanced the throttle to 100 percent, and barreled down the runaway, pogo sticks dropping away. When the airspeed indicator passed seventy knots, he began pulling back on the yoke, and the plane became airborne as its speed hit one hundred knots. The rumble of wheels on the runway faded away, and he raised the landing gear. He continued to pull on the yoke and began a forty-five-degree climb.

Airspeed rose to 160 knots. Soon the plane was invisible to the naked eye, its blue coloring the perfect camouflage against the sky. In just thirty minutes the young airman from McCook, Nebraska, had climbed to 72,000 feet, where he could clearly see the curvature of Earth. He had reached his cruising altitude and eased back on the speed, carefully keeping it between 100 and 104 knots. Forty-five minutes later, he had entered the airspace over the island of Cuba.

Now, just east of the capital city of Havana, he maneuvered his plane into position for overflight of his first target. This air force pilot, however, wasnt dropping bombsin fact his plane carried no weapons at all. Instead, he was after photos of Soviet military installations that included nuclear missiles capable of reaching and destroying cities throughout the United States.

The cockpit was quiet, and Jerry felt calm, even peaceful, despite having entered enemy airspace and knowing Soviet radar was tracking him. This was his third flight over the Communist country in just the last few days, and he focused totally on flying the aircraft, getting the photos, and returning home safely.

Jerry flicked the switch on the cockpit sensor control panel and activated the cameras. Once certain he had photographed target number one, he altered course to the southeast and in approximately forty minutes arrived and filmed his second target. The mission was going as planned, and the clear skies were holding over the 780-mile-long island covered with hills and lush green jungle.

The third and final objective was near the town of Banes, on the northeastern coast of the island. When Jerry arrived, he had been over Cuba for approximately one hour and fifteen minutes. Once over the target he started filming, got the photos he needed, shut the camera off, and started to make his turn for home, thankful for a safe and successful run.

Thats when he saw them. Through his tiny rearview mirror, two contrails stretched from Earth all the way toward his aircraft.

He was under fire.

One surface-to-air missile (SAM) had already exploded above and behind him, sending fiery shrapnel in all directions and streaks of white light against the blue sky, a deadly starburst. The second missile exploded a mere second after Jerry first looked into his rearview mirror, this one causing an explosion perhaps 8,000 feet above the plane. The blast sent a burst of adrenaline coursing through the pilots body, even though he could not hear or feel the impact. His muscles clenched, and his entire body felt as if it were shrinking. This was a natural, physiological survival response. But Jerry knew it was fruitless as he had no place to hide.