What if

Latin America

Ruled the World?

How the South Will Take the

North into the 22nd Century

Oscar Guardiola-Rivera

To Sylvia Ospina, ut pictura poesis.

To Zoe, other eyes.

To Haidy and Ceci, and the women of the Americas, Etna in ones own home.

To Bill Swainson and Kevin Conroy Scott, mystificateurs.

Contents

Introduction

History repeats itself. In June 2009, the spokesman of the Yanomami people of Brazil, Davi Kopenawa, told the British Parliament that a second war of conquest was coming. Across the globe, as governments and the boards of directors of transnational mining and energy companies race for dwindling resources in order to cover the needs of our highly energy-intensive, resource-hungry world, indigenous peoples are battling to defend their lands. All the while, young people protesting in the streets of Europe and elsewhere appeal to a sense of absent justice, accompanied by a hope that in the future justice will be done. But that hope is not their main reason for protesting. They do so because they hold on to a view of the world less as a storehouse of valuable materials and more as a complex network of relationships which extends all the way from society to the biosphere. They protest in order to save that precious common world, in the present moment, whatever the future that financiers and politicians forecast might hold. They struggle not to be reduced to irrelevance and silence, refusing to become unwilling victims of the paradoxes of over-exploitation and consumerism. They resist being propelled into the uncertain future by a violent gust, while catastrophes erupt behind and beneath them.

All around the world people are asking: What have we done to democracy? Echoing the words of Indian author Arundhati Roy, it is as if politics and the market have fused into a single predatory organism, always ready to use brute force, and with a constricted imagination that revolves almost entirely around the idea of maximising profit. If it is true that a war is coming, and that we are witnessing the endgame of the form of globalisation brought about by the first and second industrial revolutions, then Latin America is the place in the world where the battle is most likely to be decided. This time, however, those who fancy themselves as victors after the end of history will require something else, something more than the force of arms or the power of economic forces to impose their designs upon the defeated. For the latter no longer see themselves as fated to play the role of the vanquished on the stage of world affairs.

Governments must treat us with respect, Kopenawa told British MPs. We kill nothing, we live on the land, we never rob nature. Yet governments always want more. His point was that the division of labour among nations should no longer mean that some specialise in winning while others specialise in losing. This is the example that Latin America has given to the rest of the world: since the 1990s, but with particular intensity since the first decade of the twenty-first century, the world has witnessed the collapse of the dominant orthodoxy in the continent that had once been its laboratory. So called Washington consensus policies did rein in inflation but also produced the kind of deindustrialisation that in the north of Mexico and parts of Colombia or Bolivia paved the way for the brutal expansion of a shadow drug economy. They allowed for the growth of the financial and telecommunications sectors, but also brought rising unemployment and an intensifying concentration of income and land among the wealthy. Such policies deepened inequality, fragmented the labour force, and contributed to the impoverishment of the majority. Triumphant as an ideology, what in Latin America became known as neo-liberalism never managed to assert its legitimacy among the grassroots. When the time came, the majority of lower- and middle-income peoples of Latin America stood up, rejected such policies and the politicians who had implemented them, and then harnessed both democracy and the state in order to steer a course more or less finely plotted between ideals and pragmatism, but decidedly away from the orthodoxies of the past.

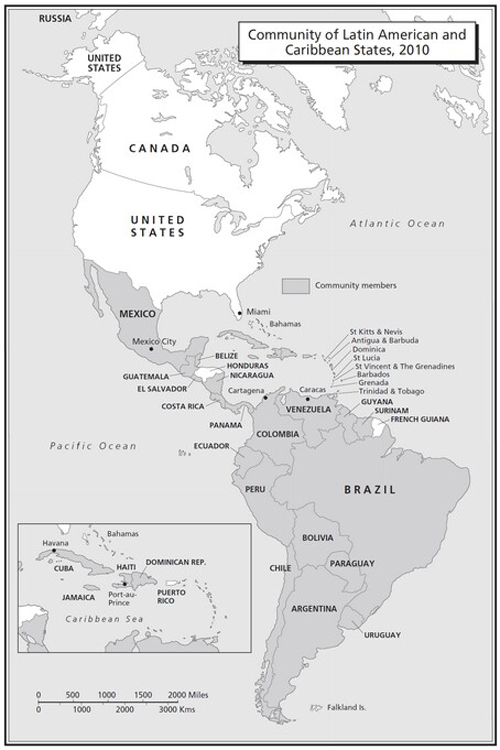

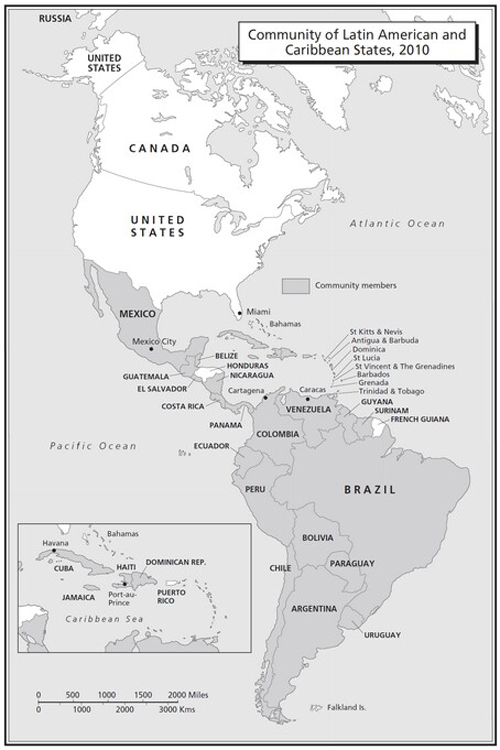

What if Latin America ruled the world? For starters, the meaning of rule would change. For too long that term has been identified with hard power and the ability to use force, more or less unilaterally, to back up ones economic and political interests. Its unlikely that the role of enforcer of last resort will disappear from global affairs, but it is becoming increasingly more difficult for any one nation or actor, say the United States or the European Union, to play that role in isolation or without dire consequences. In that respect, we are witnessing a relative decline in the capacities of so-called hard powers vis--vis soft powers. It was Brazil, rather than the P5 of the UNSC, which managed to bring Iran back to the negotiating table. And whatever the actual outcome of that attempt, even in the eyes of those who later on called for a return to the tired expedient of sanctions, the May 2010 Declaration of Tehran remains a blueprint for the future.

Then there is the matter of democracy. In no other region of the world do people hold on to the promise of democracy, and work as hard to realise it, as in Latin America. Not in China, not in Europe, and certainly not in those countries where tyrants, propped up by the very same western powers that have more recently turned against them, continue to restrain their own people. Why? The reason may be found in a question posited centuries ago by the French aristocrat Alexis de Tocqueville as he toured America: can democracy, which has destroyed feudalism and vanquished kings, stand up to the power of the rich? In Latin America, as left-of-centre governments walk a tightrope between continuity with the past and a clean break with previous policy, priority has been given to regional integration over free trade under US designs, and to pioneering conditional cash-transfer schemes that contrast with the financial policies of Europe at the expense of its people. Such schemes could evolve into a form of universal basic income that would uncouple creativity from pure profit without doing way with all economic incentives.

This is happening as a result of the force of mobilisation from below and an egalitarian tradition that more often than not speaks of money-worship as a form of idolatry, rather than because of the enlightened agenda of a few vanguard leaders from the top. To sum up, collective mobilisation, religious and indigenous traditions, and a long experience with struggles for liberation, tempered by a sense of tragedy and failure, have allowed Latin America to follow a path that differs from post-Cold War messianic visions of inevitable progress elsewhere.

Uruguayan novelist and journalist Eduardo Galeano once wrote that the part of the world known today as Latin America had been precocious: it specialised in losing, ever since those remote times when Renaissance Europeans ventured across the ocean and buried their teeth in the throats of Indian civilisations. Centuries passed, and Latin America perfected its role. Kopenawa, a spokesman for those same Indian civilisations, came from Latin America to London in 2009, donning the mantle of the prophet, to tell the west that this time things would be different. Far from fitting their stereotype as inhabitants of a region of banana republics and idealistic utopias, the peoples of South America have risen up and now stand together. They have been able to resist some of the most extreme consequences of the allegedly irresistible forces that contemporary globalisation is claimed to represent. Those forces have wreaked havoc elsewhere in the developed world, particularly after the 2008 global financial crisis.

Next page