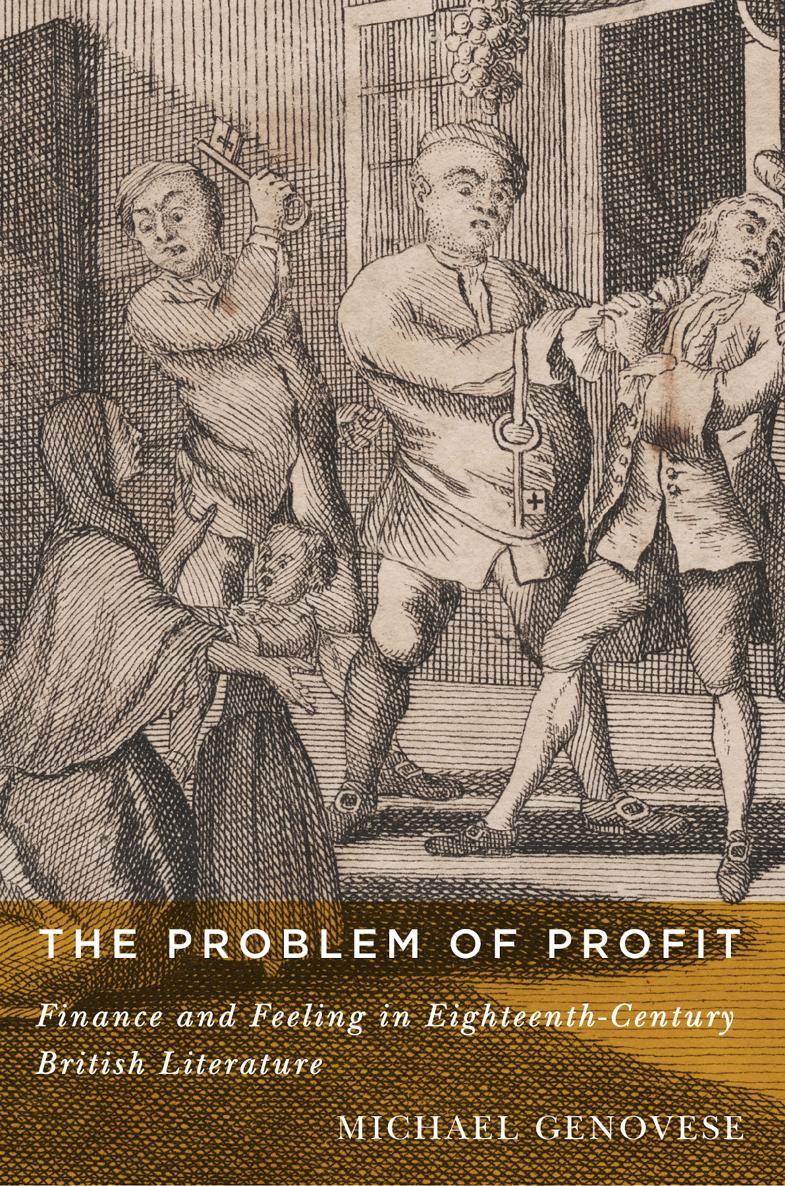

Michael Genovese - The Problem of Profit: Finance and Feeling in Eighteenth-Century British Literature

Here you can read online Michael Genovese - The Problem of Profit: Finance and Feeling in Eighteenth-Century British Literature full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: University of Virginia Press, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Problem of Profit: Finance and Feeling in Eighteenth-Century British Literature

- Author:

- Publisher:University of Virginia Press

- Genre:

- Year:2019

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

The Problem of Profit: Finance and Feeling in Eighteenth-Century British Literature: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Problem of Profit: Finance and Feeling in Eighteenth-Century British Literature" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Attacks against the pursuit of profit in eighteenth-century Britain have been largely read as reactions against market activity in general or as critiques of financial innovation. In The Problem of Profit, however, Michael Genovese contends that such rejections of profit derive not from a distaste for moneymaking itself but from a distaste for individualism.

In the aftermath of the late seventeenth-century Financial Revolution, literature linked the concept of sympathy to the public-minded economic ideals of the past to resist the rising individualism of capitalism. This study places literary works at the center of eighteenth-century debates about how to harmonize exchanges of feeling and exchanges of finance, highlighting representations of communitarian, affective profit-making in georgic poetry as well as in the work of Joseph Addison, Daniel Defoe, Richard Steele, Sarah Fielding, Henry Fielding, David Hume, Samuel Johnson, and Laurence Sterne, among others. Investigating commercial treatises, novels, poetry, periodicals, and philosophy, Genovese argues that authors conjured alternatives to private accumulation that might counter the isolating tendencies of impersonal exchange.

However, even as emotional language and economic language arose together in the 1700s, the attendant aspiration to form a communitarian economy in Britain was not fulfilled. By recovering an approach to moneymaking that failed to thrive, The Problem of Profit argues for the relevance of an unfamiliar narrative of capitalistic thought to todays anxiety over the discord between personal ambition and public good.

Michael Genovese: author's other books

Who wrote The Problem of Profit: Finance and Feeling in Eighteenth-Century British Literature? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.