University of Virginia Press

2020 by the Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia

All rights reserved

First published 2020

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Sider Jost, Jacob, author.

Title: Interest and connection in the eighteenth century : Hervey, Johnson, Smith, Equiano / Jacob Sider Jost.

Description: Charlottesville : University of Virginia Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020015349 (print) | LCCN 2020015350 (ebook) | ISBN 9780813945040 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780813945057 (paperback) | ISBN 9780813945064 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: English literature18th centuryHistory and criticism. | Interpersonal relations in literature. | Literature and societyGreat BritainHistory18th century. | Interest (The English word)

Classification: LCC PR448.I55 S43 2020 (print) | LCC PR448.I55 (ebook) | DDC 820.9/005dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020015349

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020015350

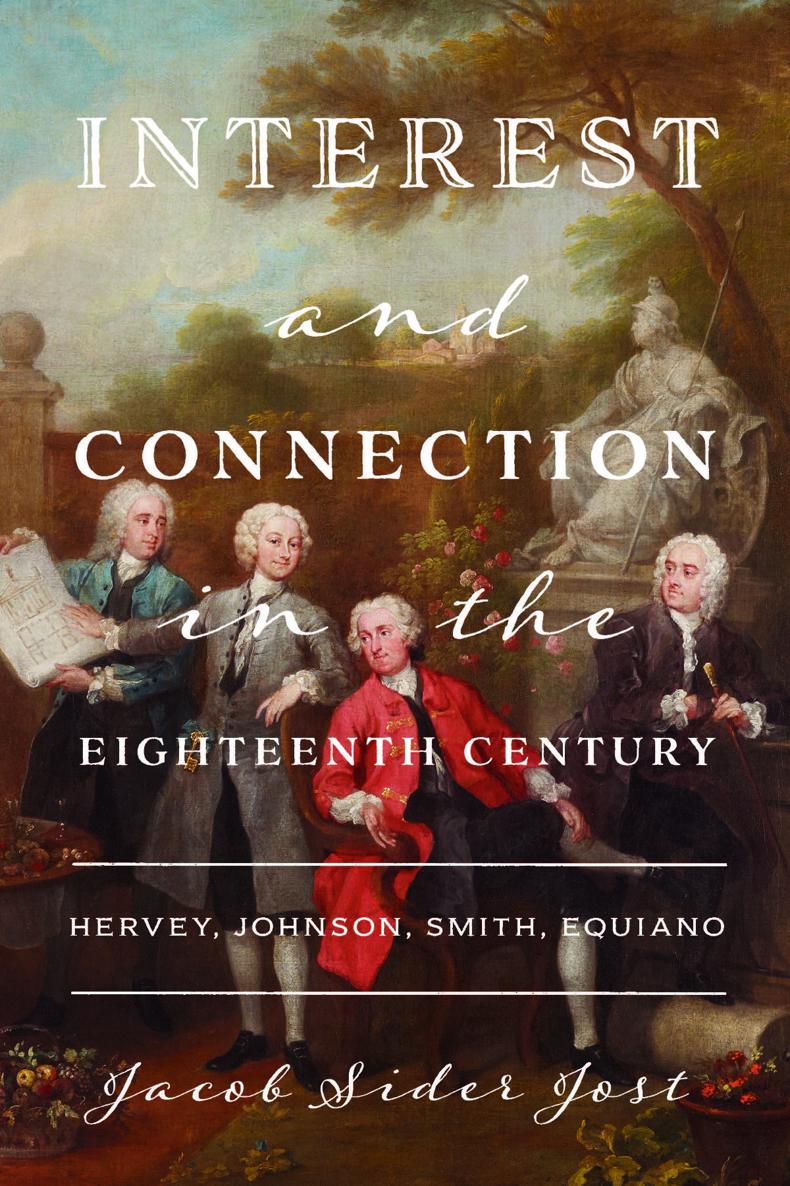

Cover art: The Hervey Conversation Piece, William Hogarth, 173840. (Ickworth, Bristol Collection; acquired through the National Land Fund and transferred to the National Trust in 1956; National Trust Images)

W e live in interesting times. When we examine a text or work of art, we seldom ask, as the medieval scholastics did, whether it participates in the beautiful and the good. We are more likely to talk about whether or not it is interesting or reflect on what we find interesting about it. When we divide our political world into groups, we do not use the ancient Roman categories of patrician and plebeian or the early modern English categories of lords and commons; rather, we talk about class interests, special interests, and interest groups. Homers Greeks fought for kudos, glory, while the medieval crusaders claimed that they were following the will of God. We explain war and peace by imagining that rulers pursue their respective national interests. When we analyze, model, or predict the actions of individuals, we tend not to talk, as Plato did, about the struggle between reason and passion within the will. Instead, we postulate self-interest as the basis of human behavior. And when we give a price to have access to money, we do not follow the Bible or its medieval readers in branding the transaction with the morally pejorative title of usury. We are simply paying interest. In each of these disciplines or discourseswhat we would now call aesthetics, political science, international relations, economics, and financeinterest emerges as a concept at some point between the Middle Ages and the early nineteenth century. When it does, new ways of thinking become possible.

The idiom of interest has likewise changed the way we understand romance. Consider the following two autobiographical passages, written just over seven hundred years apart by two authors whose works are preoccupied with love. The first: At that very moment, and I speak the truth, the vital spirit, the one that dwells in the most secret chamber of the heart, began to tremble so violently that even the most minute veins of my body were strangely affected; and trembling, it spoke these words: Ecce deus fortior me, qui veniens dominabit michi (Here is a god stronger than I who comes to rule over me). Dante understands the sight of Beatrice, when both she and the narrator are eight years old, in terms of divine possession and domination: the eponymous new life of the thirteenth-century Vita Nuova begins when the god of love conquers the poet. Everything that Dante was before that moment is driven out: From that time on, Love governed my soul.

The philosopher Stanley Cavell, whose 2010 memoir has the more ironic title of Little Did I Know, does not see love as a break or as a new life. On the contrary, Cavell brings his full social, emotional, and intellectual self to the pursuit of love. Recalling the winter of 1963, he describes the wish to test one side of himselfan early midcareer Harvard philosopher in New York for a conferenceagainst a side that feels reverberations of loneliness, desire, and apprehension toward Cathleen Cohen, just over half his age and halfway through her senior year at Radcliffe:

When I phoned her then from my hotel she was about to dress for a wedding rehearsal in which she was a bridesmaid and afterward have dinner with the participants. When she named the hotel in which the event was to take place, I noted that I was meeting friends for drinks at the Algonquin Hotel, which was near her destination. She agreed to my suggestion that she step up the tempo and make room to join us for half an hour on her way. It was in obvious respects a pointless plan, but the group of friends I was meeting included Jack Rawls and Rogers Albritton and Ronald Dworkin and Marshall Cohen, and I suppose I wanted a signal opportunity to have the two sides of my life, as it were, or the two imagined sides, meet on an interesting neutral field and test each other.

Cavell brings his friends, his philosophical pursuits, and his artistic tastes (he was a gifted saxophonist, and he and his fellow philosophers ask Cohen to recommend Greenwich Village jazz venues) to the table of the Algonquin bar, while Cohen for her part is in her home city, on her way to a wedding rehearsal and dinner with friends. The neutral field where the professional-social and lonely-desiring sides of Cavells life meet is interesting because it occurs where Cavells and Cohens whole selvesall of their interestscan be present. It is interesting because Cavells episode imagines human intimacy not through a metaphor of conquest but with the mixture of involvement and prudence that is compacted in the modern idiom, first found in seventeenth-century literature, of romantic interest. When we say Im interested in N or N is interested in M, we posit an affective and erotic world at home over drinks at the Algonquin rather than the vital spirit of Dantes narrator conquered by the god of love.

In examining this passage, I am not so much interested in the romantic fortunes of Cavell and Cohen as I am in the concepts and assumptions about intimate life through which Cavell recollects their encounter. Im just kidding: thats nonsense. I want to know how the story ends, and I hope you do too. Though it had seemed in obvious respects a pointless plan, Cavell reports that in the event the half-hour date was an inspired idea, and the pair embark a year later on a marriage that was to last over a half century, until Cavells death in 2018 (439). Since this is a book about interest, I am, however, interested in why contemporary scholars so often find it necessary to introduce their work by telling their readers or auditors what they (the scholars) are and are not interested in, especially when the line between interest and its absence seems to be drawn perversely or to impose a false choice. I am not so much interested in the rights and wrongs of urinating in public, as in the discursive tensions that frame this topic, announces the abstract to a 2010 article by a sociologist of the nighttime use of public space in twenty-first-century Britain. I think that both of those things are in fact worthy of interest and deserve consideration together: that is why I read part 1 of