VIKING

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

penguin.com

Copyright 2018 by David D. Kirkpatrick

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

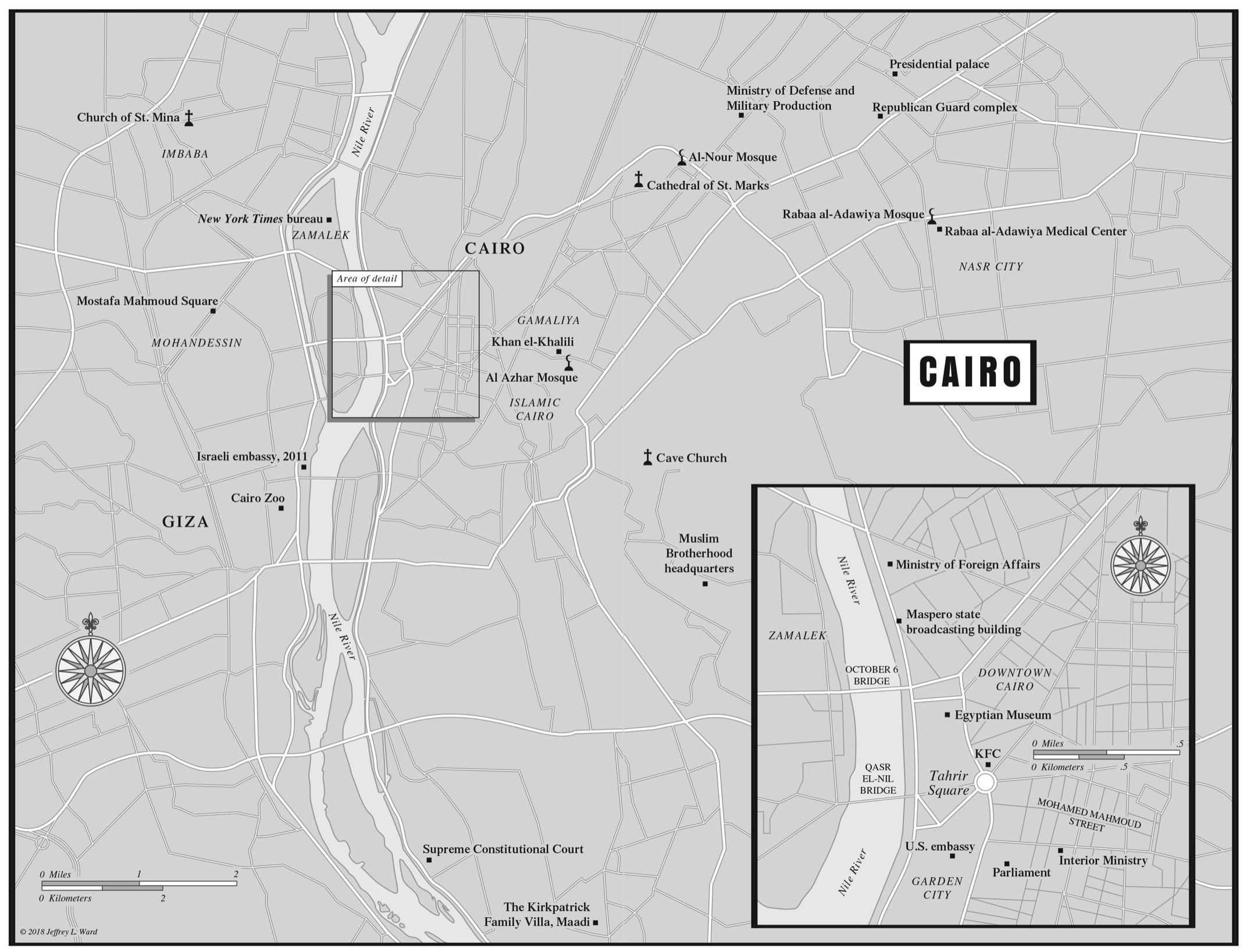

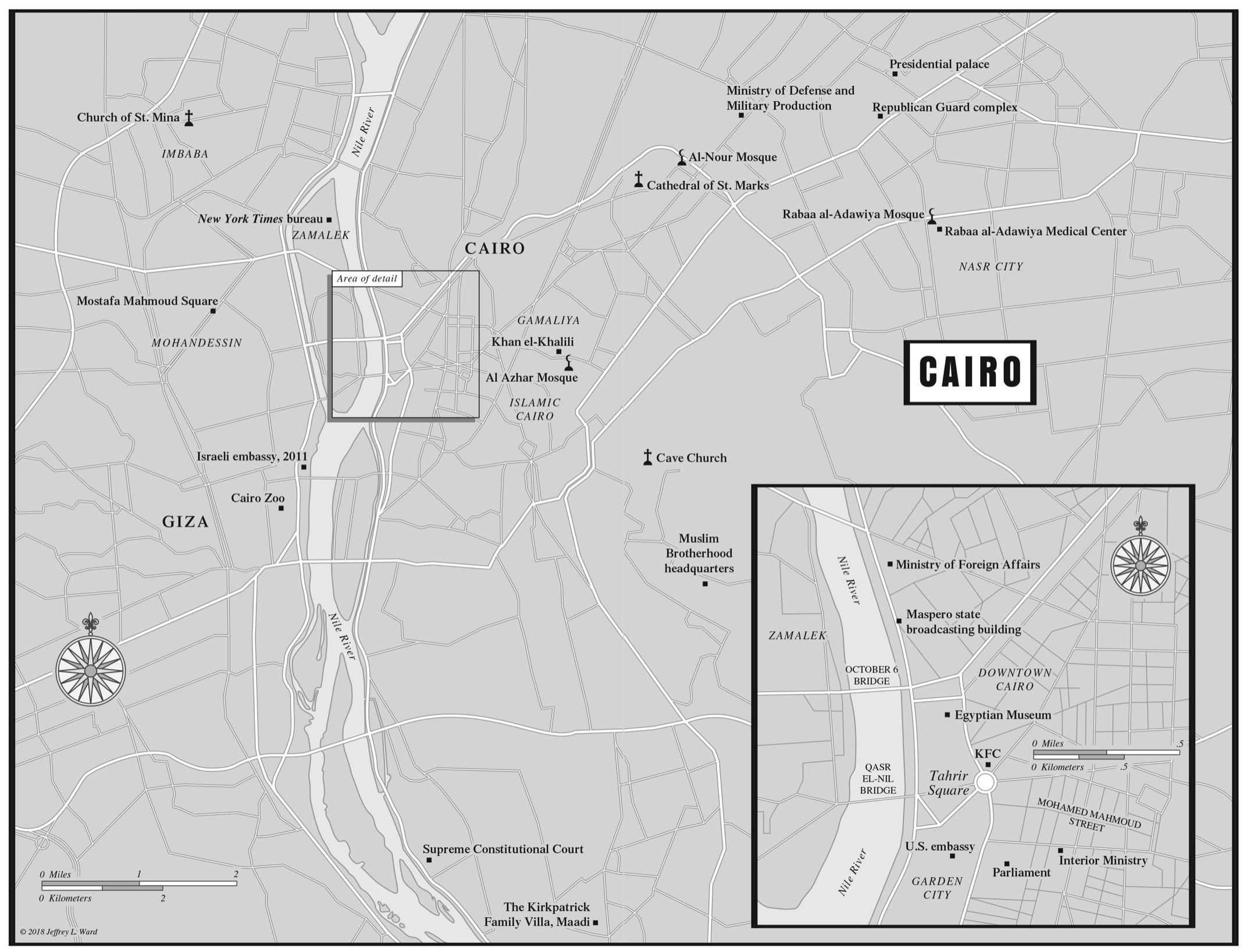

Map illustration by Jeffrey L. Ward

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kirkpatrick, David D., 1970- author.

Title: Into the hands of the soldiers : freedom and chaos in Egypt and the Middle East / David D. Kirkpatrick.

Description: New York, New York : Viking, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2018025162 (print) | LCCN 2018028471 (ebook) | ISBN 9780735220645 (ebook) | ISBN 9780735220621 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Egypt--Politics and government--2011- | Arab Spring, 2010- | Egypt--History--Protests, 2011-2013. | Egypt--History--Coup d'etat, 2013. | Middle East--Politics and government--21st century.

Classification: LCC DT107.88 (ebook) | LCC DT107.88 .K57 2018 (print) | DDC 962.05/6--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018025162

Version_1

For Laura Bradford, who never signed up for any of this.

Contents

1

Whoever Drinks the Water

Driving east from Tunis may be the best way to take in the miracle of the Nile. The road follows the Mediterranean coast for about seventeen hundred miles. Almost every inch of it is brown twelve months a yearrock and sand baking in the sun. Then you cross an invisible line at the edge of the Nile Valley. Everywhere is an eruption of green. Not even the congestion of Cairo can contain the riot of vegetation.

For millennia, no other territory in the Middle East produced such a bounty. Where the yearly flooding of the Euphrates was violent and destructive, the cycles of the Nile were gentle and predictable. A truism holds that the histories of Egypt and Iraq follow their rivers. Medieval sultans dug a well, known today as the Nile-o-meter, on Rawda Island in Cairo, to measure the water level. The annual rise determined how generous the crops would be that year, and the sultans taxed the peasants accordingly. Farming was that easy. The Nile Valley became the breadbasket of the Arab world. Egyptians swelled with pride in their river. Whoever drinks the water of the Nile will return again to Egypt, the old saying goes.

Egyptians also like to say that they have been rallying around grand national projects since the Pharaohs built the temples of Thebes. After taking power in 1952, President Gamal Abdel Nasser decided to build a great dam at Aswan, near the Sudanese border, to harness the Nile for hydroelectric power. Abdel Nasser promised a dam more magnificent and seventeen times greater than the Pyramids.

Secretary of State John Foster Dulles announced in 1955 that the United States and the United Kingdom would provide $70 million in assistance for construction of the dam. But he did not like Abdel Nassers denunciations of colonialism, or his refusal to ally exclusively with Washington. After seven months, Dulles withdrew the offer. Abdel Nasser turned to Moscow.

The dam became a monument to Stalinist engineering. Its construction displaced one hundred twenty thousand Nubians, the dark-skinned Egyptians indigenous to the area. The lake formed by the dam nearly demolished the breathtaking Pharaonic temples at Abu Simbel; UNESCO saved them by paying Western European contractors to relocate the complex, stone by stone, on drier ground. The finished dam stopped the flow of silt and nutrients that had kept much of the Nile Valley so fertile for centuries. The depletion of the water devastated the farmlands downstream and the fishing around the mouth of the Nile. The slowing of the current led to an explosion in waterborne diseases like schistosomiasis.

To fight the disease, Abdel Nassers successors launched a massive campaign of inoculations. But government health workers reused unsterilized needles. That set off a hepatitis C epidemic that raged on for decades. About one in five Egyptians was infected with virus C, as Egyptians called it, in imported English. Barbers spread the disease by reusing blades, so sensible Egyptian men carried their own personal shears to haircuts, and I did as well.

The adage about drinking the Nile water lives on today as black humor. The river is so filthy that your first stop would be a hospital. Yet Egyptian schoolchildren are still taught to celebrate Abdel Nassers High Dam as an unalloyed triumph. I think of the dam whenever I get a haircut: a parable of centralized planning and unaccountable power.

I had the luck to be an American journalist living in Cairo during the thirty months when Egyptians broke free of the autocracy that ruled them. Their escape set off revolts from Benghazi to Baghdad. But the old authoritarian order had only hidden underground, not shattered. It returned to take revenge. A reinvigorated autocracy did its best to blot out the memory of those thirty months of freedom. Let me tell you the story.

2

City of Contradictions

August 14, 2010January 23, 2011

My introduction to Egypt was an iftarthe ritual meal at dusk to break the Ramadan faston a gritty day in August 2010.

My family and I had moved that week into a one-story villa in Maadi, a leafy district about six miles up the Nile from the New York Times bureau on the island of Zamalek. Both neighborhoodsMaadi and Zamalekare full of Western expats and Egyptian old money. I had a twenty-minute drive to work if the streets were empty. Usually the lawless traffic made the trip more than an hour. Mercedes sedans and Land Rovers veered around donkey carts stacked with carrots or garlic. Families of four or five crammed onto the backs of Korean motorcycles, and mothers rode sidesaddle with infants in their arms. My wife, Laura, and I had hauled our one-year-olds car seat all the way from Washington. We felt so fussy.

I was drawn to Egypt in part by the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. I knew the roots of Al Qaeda and its ideology ran back to Egypt. Also, I had turned forty in 2010. I wanted a change from Washington, where I had reported for the previous six years. That was about the extent of my preparation for my posting in Cairo.

I was thrilled with the job. Egypt, home to a quarter of all Arabs, had set every major trend in religion, culture, and politics across the Arab world for more than half a century. Egypt commanded the largest Arab army and held together the region. It kept the peace with Israel. After Israel, Cairo had received more United States aid over the decades than any other countryover $70 billion, at a rate of $1.5 billion a year at the time I arrived. Whatever happened in Egypt was in a way an American story.

The skinny apparatchik in charge of the international news media had welcomed me to Egypt just a few days earlier. He told me that the Foreign Ministry had recalled him from the San Francisco consulate to apply his public relations expertise to the upcoming reelection of President Hosni Mubarak, who was then eighty-two and seeking his seventh five-year term in office. But the genial bureaucrat, Attiya Shakran, talked mostly about how sorry he was to leave San Francisco. Expect laziness and dysfunction from Egyptians, he told me. IBM in Egypt stood for