The dispatches collected in this book originally appeared on the NYRblog, the online supplement of The New York Review of Books. , The Battle for Egypts Future, appeared, in slightly different form, in the April 28, 2011, issue of The New York Review of Books.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

by Timothy Garton Ash

DISPATCHES FROM THE REVOLUTION

PREFACE

All revolutions are mysteries, but they are not all the same mystery. Why there? Why then? Why thus? Yasmine El Rashidis blog dispatches make a unique eyewitness contribution to unraveling the mystery that is the Egyptian revolution of 2011.

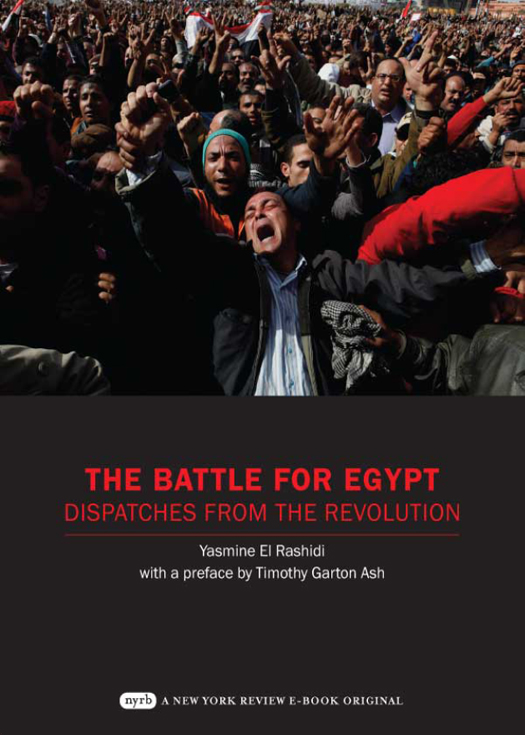

Start by looking carefully at the end of each blog. You find not just a date but also a time: January 30, 8:15 PM , February 3, 1:45 PM . Had that been 8:30 PM , or 2:15 PM , it might have been a whole new story. Thats what revolutions are like. And so the first thing El Rashidi gives us is something that historians can never fully recover: a sense of what people did not know at the time. The excitement and tension of the unknown. For when those hundred people from the Shubra district started walking down toward Tahrir Square on the afternoon of Monday January 25, with El Rashidi among them, they had no idea what would happen to them in the next five minuteslet alone that eighteen days later they would have forced president Hosni Mubarak to resign, and changed the Arab world for ever.

But she gives us more than just the immediate picture of what it was like to be there, with memorable vignettes such as the female soldier wearing a rose behind her ear. Unlike most of the foreign correspondents present, she knows the language, places, backgrounds, social forces, and, not least, individual people. At one demonstration, she spots Hazem Moussa, the son of Amr Moussa, secretary-general of the Arab League; at another, Karim El Shafei, whom she identifies as CEO of one of the countrys largest investment funds. Such details matter.

She shares with us the emotional highs and lows, the confusion, the frantic rumors. She also documents the humor and spontaneous creativity characteristic of many revolutions. One protesters placard calls on Mubarak to resign soon because my arm is aching from holding up this sign. She translates some choice passages of revolutionary rhetoric. An Imam at Friday prayers, for example, praises the countrys youth calling for democratic rights and, yes, free speech. But she does not omit the more worrying parts. Sheikh Yusuf al-Qaradawithe Muslim Brotherhood guru who as recently as October 2009 called for a day of rage against the Danish cartoons of Muhammadappeals to the assembled crowd to pray for the Muslim reconquest of Jerusalem.

In short, she does the classic reporters job, with her open notebook attracting unwelcome attention from police and pro-Mubarak thugs. Obviously brave and resourceful, she nonetheless confesses to her moments of fear, making them part of the story. As a woman, she offers special insights into one of the most important dimensions of these events: the active, even leading, role played by womensome wearing the hijab, some not.

Last but not least, she demonstrates the utter intertwining, in the life of educated Egyptians like herself, of real life, old media, and new media. She records a manual to the Egyptian revolution arriving by e-mail, as a pdf. Her reportage slides seamlessly from the drama on the streets, to television events like the famous interview with Wael Ghonim, to the latest chatter on Facebook and Twitter. El Rashidi is a poetess of the Twitter hashtag: #Egypt, #Jan25. Future historians of the Egyptian revolution may add #El-Rashidi.

Timothy Garton Ash

Oxford, April 2011

1. Hosni Mubarak, the Plane Is Waiting

Cairo on the morning of January 25 felt like something of a ghost town. Few civilians were to be found on the streets, most stores were shuttered, and the typically heaving downtown was deserted. It was a national holiday, and in the central town square, named Tahrir, or Liberation, even cars were scarce, and parking spacesalways sparsewere in abundance. The only conspicuous presence was that of Egypts police and state security. Rows of their box-shaped olive-green trucks lined thoroughfares and narrow side-streets, in some cases blocking them off for miles. Beside them were battered cobalt blue trucksthe ones used to whisk away prisoners and detainees. Throughout the downtown area and in neighboring districts, police and informants (easily identified by their loitering presence, darting eyes, and frequent two-second phone calls) were gathered around the otherwise empty major arteries of the city. Hundreds of them. Many wore black cargo pants, bush jackets, and clunky army boots. Many more were in plain clothesstanding on street corners, at calculated intervals on sidewalks, in building entrances, on bridges, and in the few cafs open on a day when almost everything was closed.

Youth activist groups had designated January 25 as Freedom Revolution Day. The uprising in Tunisia, which in four short weeks sent President Zine el-Abidine Ben-Ali packing, had been closely watched by Egyptian activists and opposition leaders. They included members of the once-popular Kifaya (Enough), the youth-based April 6 movement, Karama, the Popular Democratic Movement for Change (HASHD), the National Association for Change, founded by former IAEA Chief Mohamed ElBaradei, the Justice and Freedom Youth movement, and the Revolutionary Socialists. On January 20, some thirty leaders from these groups met in the decrepit headquarters of the Center for Socialist Studies in central Cairo to help organize a mass demonstration against the repressive Egyptian regime.

Egyptians have many grievances, with sectarian strife, police brutality, inflation and skyrocketing prices, and the vicious clampdowns by the government on any dissent topping the list. In the lead-up to last Novembers parliamentary elections, press freedoms were curbed and dozens of opposition members were jailed. The elections themselves were widely seen as a sham, yielding a sweeping victory for President Hosni Mubaraks ruling National Democratic Party. Then, on New Years Eve, a suicide bombing outside a church in Alexandria left twenty-two people dead and more than eighty injured.

The activists plan for January 25 was to send tens of thousands of Egyptians into the streets, and to have them stay there until President Hosni Mubarak gave in to demands: justice, freedom, citizen rights, and an end to his thirty-year rule. The organizerscomprised, largely, of public university graduates in their twentieshad called on Cairenes to gather at several locations across the city, prepared for nights in the streets and armed with camerasto document police brutality, which has come to be expected at any public protest here.