FOR ADO

THANKYOU, SORRY, THANKYOU

CONTENTS

Guide

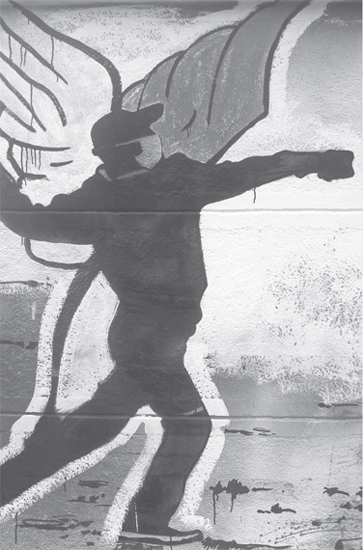

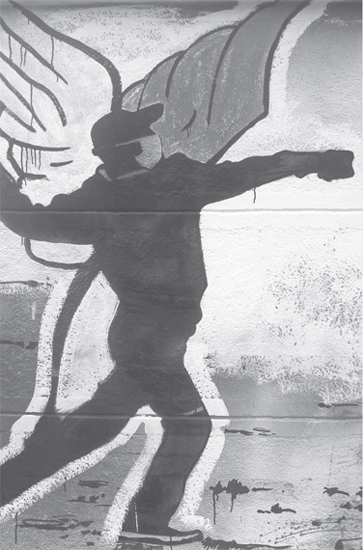

I N CAIRO IN THOSE EIGHTEEN DAYS (THOSE DAYS! ALREADY GONE AND replaced by the nostalgia of the misremembered), every day was a new day to be written. I would wake up in the morning and the protesters on Tahrir were waking too, rising from their flower beds, shaking themselves anew, and wondering too: what would this new day bring? Every day we had no idea what would happen, every day seesawed between joy and death. Between the grand metaphysics of a great hope and its realization was the physical reality that opposed it: a stick, a rock, a bullet.

With hindsight its easy enough to offer reasons for the Egyptian revolution. Analyzed narrative, neat and ordered. Like history in a textbook, each event a chapter I learned when I was twelve: the causes of the French Revolution, the causes of the Russian Revolution, the causes of the First World War reduced to a list, (a) (b) (c) (d) and (e). In this way we can catalog Mubaraks Egypt quite academically:

aging dictator

no succession plan (fear that the dictators widely perceived corrupt businessman son, Gamal, was being groomed to take over)

obviously fraudulent parliamentary election the previous December

increase in number of opposition groups over the past five years

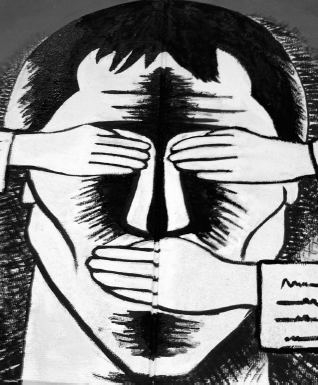

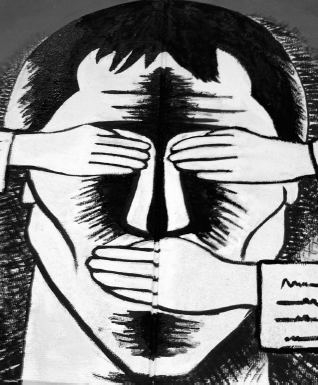

brutality of state security

outrage at the graphically horrifying photographs of Khalid Said, a nice middle-class young man, after he was beaten to death by the police

a bulging youth demographic

widespread use of social networking

the example of Tunisia

Is this clear? Do we understand better? We can read words on a page that have been organized for us. But notice the volume of white space around the words. What is hiding in this white space? Half-considered tangents and impulses, groping comprehensions and misapprehensions... so much of history is hiding in the white spaces, dismissed as marginalia.

W hen the crowds massed in Tunis and then in Cairo I felt a great tug in my gut. I had spent more than a decade in the Middle East. Many conversations with Iraqi Syrian Lebanese Egyptian friends, many evenings, shawarma arguments, beers on the table, debating to and fro and cracking black jokes, throwing our hands in the air, caught between two barbed-wire fences: foreign nefariousness (colonial carve-up; American petro-interest and military foot stamping) and homegrown brutal dictatorship.

Yes, I would agree, we British Americans are murderous and hypocrites. You couldnt come in from a bloody Baghdad street and conclude any different. But when I wrote about prisons and jackboot mustaches and suicide bombs and the violence against women or Christians or Shia or indeed anyone-who-was-different, I would whisper to myself: murderous and hypocrites, yes, but we are also self-determination and the Magna Carta and Tom Paine, we are the Bill of Rights and the Enlightenment and a certain sense of decent cricket behavior. And I would be angry with the Arabsall of them together, because no one can help generalizing in the privacy of ones own thoughtsand silently vent my frustrations: Why must you always be subjective, instead of objective? Can you dare to imagine the rule of law in these sandy lands? If you want something, do it yourself instead of demanding that someone else do it for you and then complaining about foreign interference. Plenty of times I heard my thoughts echoed when Arabs themselves complained to me about Arab shibboleths: pride and patriarchy; clan and religion and that particular pathology of an inferiority complex armored with a sense of superiority.

But I never believed that there was something inherently Arab about Arabs that meant they were condemned to strongmen or to fanaticism. Everyone I ever met in Arabland, every story I ever wrote, seemed to suggest a greater universality of hope and dream. It is very obvious to people who are not free that they are not free; it was very obvious to me that they would have liked to be.

I watched the crowds gather on the streets on TV. They carried smiles and determination. They were shouting, The people want the fall of the regime. Shouting! My heart thumped with them. I e-mailed editors to send me, please send me! One oclock in the morning, dishes in the sink, I opened my e-mail to read that Oz had pulled his curtain back an inch and typed two words: Yes Go.

H indsight eats stories. It might seem inevitable now that Mubarak would fall; inevitable, too, that two and a half years later the army would take back control. But at the time there was nothing sure about it at all. There were street battles, there were giddy skittish youths, there were tanks, there was an ever-present undertow of reactionaryness. One person would say, We are not leaving until he leaves! and thrust their hand in the air defiantly. And the person standing next to them would say, Yes, but we must be careful. We should wait until things calm down before there are elections. And the man next to him would say, We should all go back to work because this disruption is destroying the country. And his friend would nod and agree and add, I trust the army, the army will take care of everything. And then one of the young activist kids hearing this would shake his head furiously and say, No, they are all the same, all the old guard! And then another angrier voice would interrupt: Lets burn down the Interior Ministry! No, would come the reply of an old schoolteacher, no, peaceful, peaceful!

The crowd was a single thing, but it was made up of individuals and in each Egyptian head resided several competing opinions. Calm down vs. burn down; Islam as sanctuary as mantra as terrorism; army good, bad, the only solution; strongman Pharaoh regime parliamentwhat does a prime minister do?voting voting with your feet running away, from, toward, around the corner to catch your breath. This was as true for an army officer stationed at a Cairo crossroads or a pro-Mubarak thug or an official of the ruling party as it was for a revolutionary youth. Every day Egypt would wake up and have no idea what it would do that day, or what would happen. Events hung between one possibility that was active agency, and another that would be delivered as fate (which is to say by Allah or the powers-that-remained) but which was to be accepted as beyond your control. For some Egyptians this was the freedom of their own blank page to write, for others it was terrifying and mystifying and exhausting.

The precariousness of not knowing what would happen next persisted after Mubarak fell. Sparks were tossed into the air and the hot wind blew them hither and thither, alighting in the midst of the demos: protests, sit-ins, strikes, football matches, factories, courthouses, police stations, car parks, train stations. Everything became mixed up together: the old regime with all the new yelling, protesters and provocateurs and secret policemen and military trials and journalists hauled before judges on libel charges. It was very confusing, and the events overlapped each other and the crowds swept over the events like waves.