Allen Lane is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Let the conversation begin...

Who are they and who are we?

Ahmed Fouad Negm, Egyptian poet (19292013)

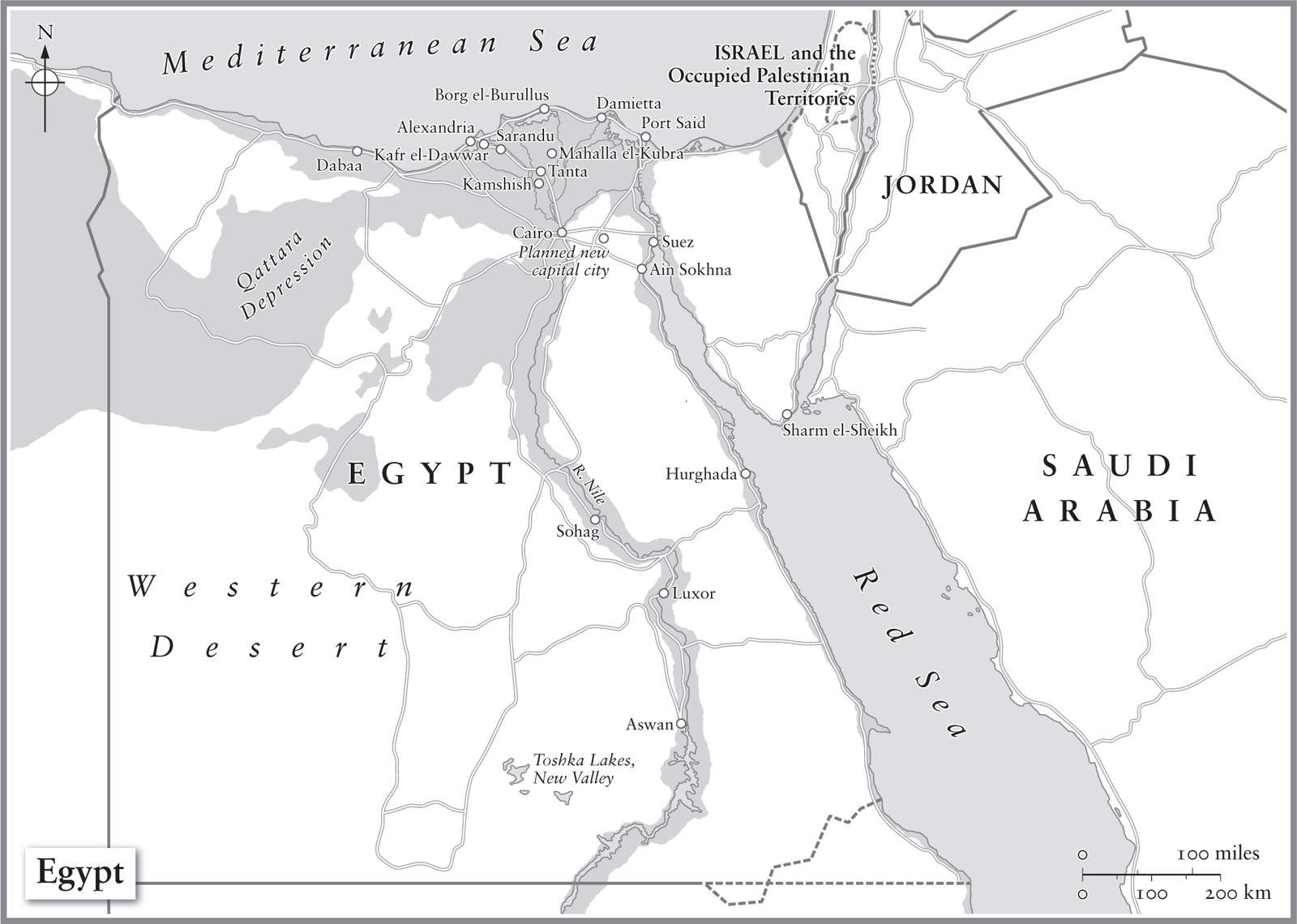

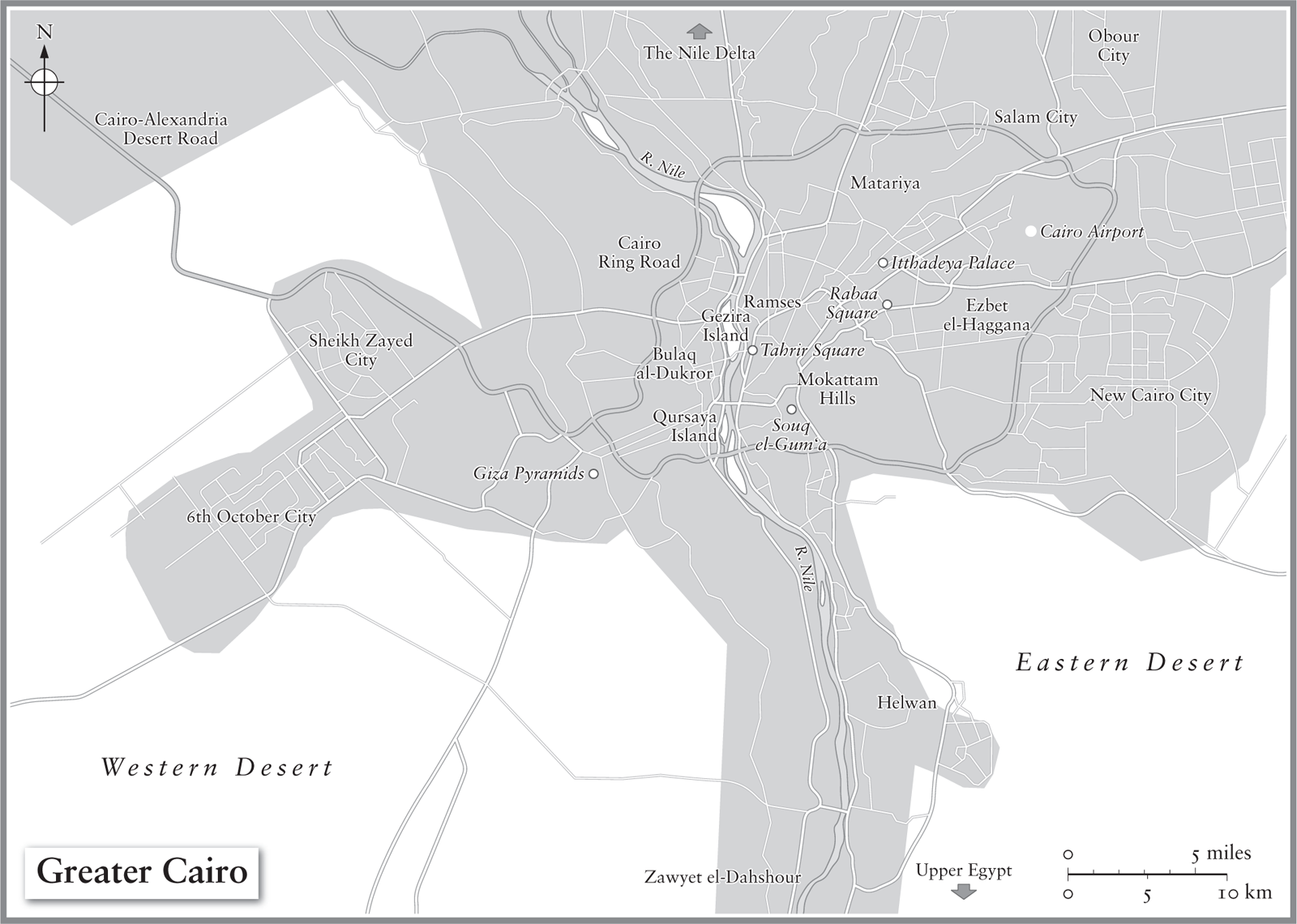

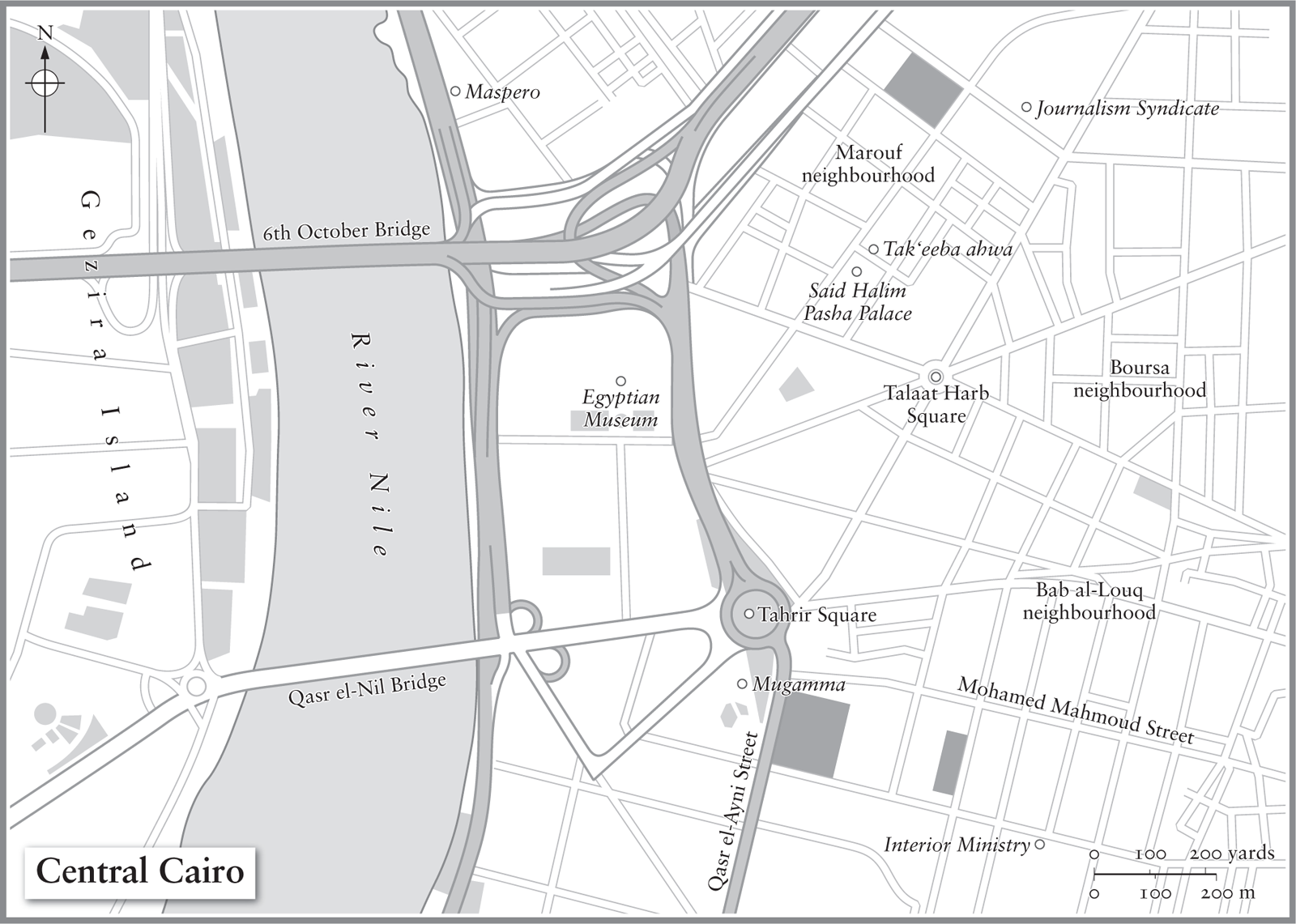

List of Maps

Note on Transliteration

The transliteration of Arabic words into English is notoriously tricky; any standardized system must inevitably sacrifice at least one of accuracy, simplicity or complete consistency. In this book, Arabic words have been transliterated according to a system that aims to render them familiar to Arabic speakers and pronounceable for non-Arabic readers.

Nearly all Arabic vocabulary is transliterated from Egyptian Colloquial Arabic, rather than the more formal Modern Standard Arabic. Where an Arabic word is already commonly known in English, the familiar English spelling has been used even when it conflicts with the transliteration system. The same applies when a person or institution has already adopted a particular English spelling of their own name.

Prologue: The People Want

The video is shot from a balcony, and its style is familiar. A shaky, handheld camera, tracking the action back and forth. Figures below, mustering on some unspecified stretch of tarmac and urging one another forward. The chants of the crowd, and eventually their screams. El-shaab, yureed, isqat el-musheer! El-shaab, yureed, isqat el-musheer, they bellow, again and again. El-shaab, yureed, isqat el-musheer! El-shaab, yureed, isqat el-musheer!

The rhythm of the words is like a mounting drumbeat, steeling the children and they are children, some almost in their early teens but most no more than nine or ten years old for the battle ahead. In Arabic, el-shaab, yureed, isqat means The people want the downfall of and el-musheer is the field marshal. Because this is Egypt in early 2012, a year on from the toppling of former president Hosni Mubarak, the field marshal being referred to must be General Mohamed Hussein Tantawi, the head of a junta under whose watch more than a hundred revolutionary demonstrators have been killed and thousands more have been dragged before military tribunals. Calling for his downfall is a brave and dangerous thing to do. Yet still, the children chant. And now they have gathered strength in numbers, and are staring defiantly at something, or someone, which stands unseen beyond the left-hand edge of the screen. There are more and more children in the shot, clapping and chanting and feeding off each others energy, and suddenly imperceptibly, without a signal from any leader the air distorts a little, something intangible cracks, and for a moment the whole world seems to tip on its head and bevel with possibility. You can feel this shift in the blurry pixels, you can feel it surging through the children like a rustle of volts through the bones, you can feel something ineffable is building and building and now there, its started! The march begins and they are advancing, their eyes trained on the prize; off to the left towards that invisible adversary, arms in the air and chests puffed forward, and the jittery camera is following their progress, and that off-screen enemy is silent, and watching, and waiting.

And then there is a noise.

And now there is choking and spluttering and shouts and confusion and everyone begins to turn and run back the way they came. Everyone, that is, but the smattering of children who have dropped to the floor in a heap of clothes and flesh, everyone but the children now lying completely still amid the madness.

And yet, despite all this terror, the fleeing survivors quickly rally themselves and gather in a group once more. The injured and lifeless are retrieved, that melodic drumbeat thuds again in the roofs of the childrens mouths, and within moments the crowd has returned to its starting position, unbowed and eyes blazing off to the left, everyone readying themselves for another reckless push into the unknown. El-shaab, yureed, isqat el-musheer! they roar. El-shaab, yureed, isqat el-musheer!

This is Zawyet el-Dahshour school, twenty miles south of Cairo city centre, and what youre watching on screen is playtime.

Egypts revolution has been misunderstood, and a great deal of that misunderstanding has been deliberate. A process that began on 25 January 2011, and which will continue yet for many more years to come, has been framed deceptively by elites both within Egypts borders and beyond. The aim of this deception has been to sanitize the revolution and divest it of its radical potential. Over the past half-decade the Arab Worlds most populous nation has been engulfed by unprecedented turmoil, the result of millions of ordinary people choosing to reject the political and economic status quo and trying instead to build better alternatives. Their struggle has pitted them against a violent and exclusionary state, an entity not confined within neat territorial limits but rather something enmeshed with global capital and thus linked inextricably to systems of governance that structure all our lives. By warping the lens through which most of us view and interpret that struggle, those who benefit most from the way things are hope to prevent us from thinking too seriously about the way things could be.