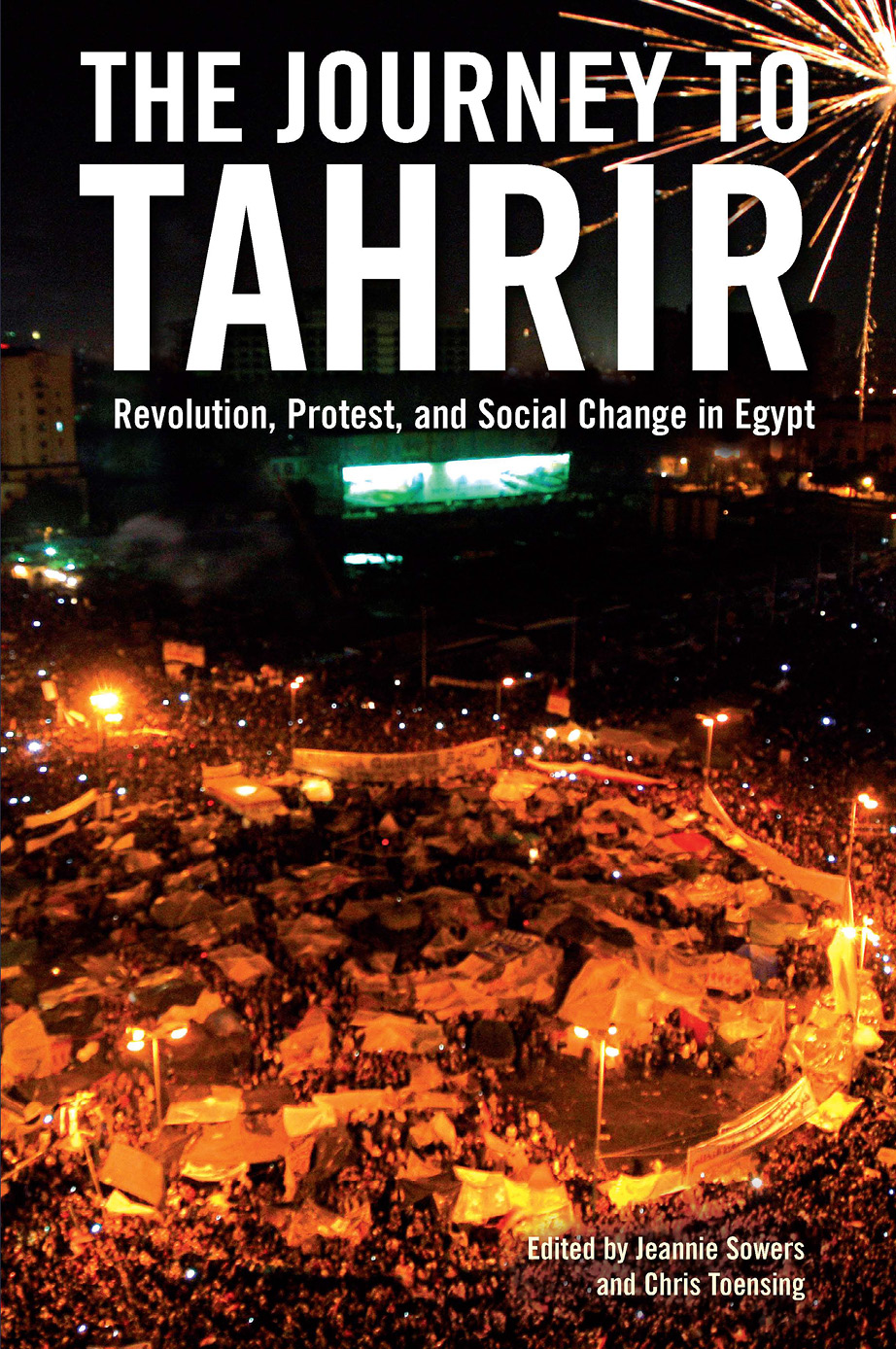

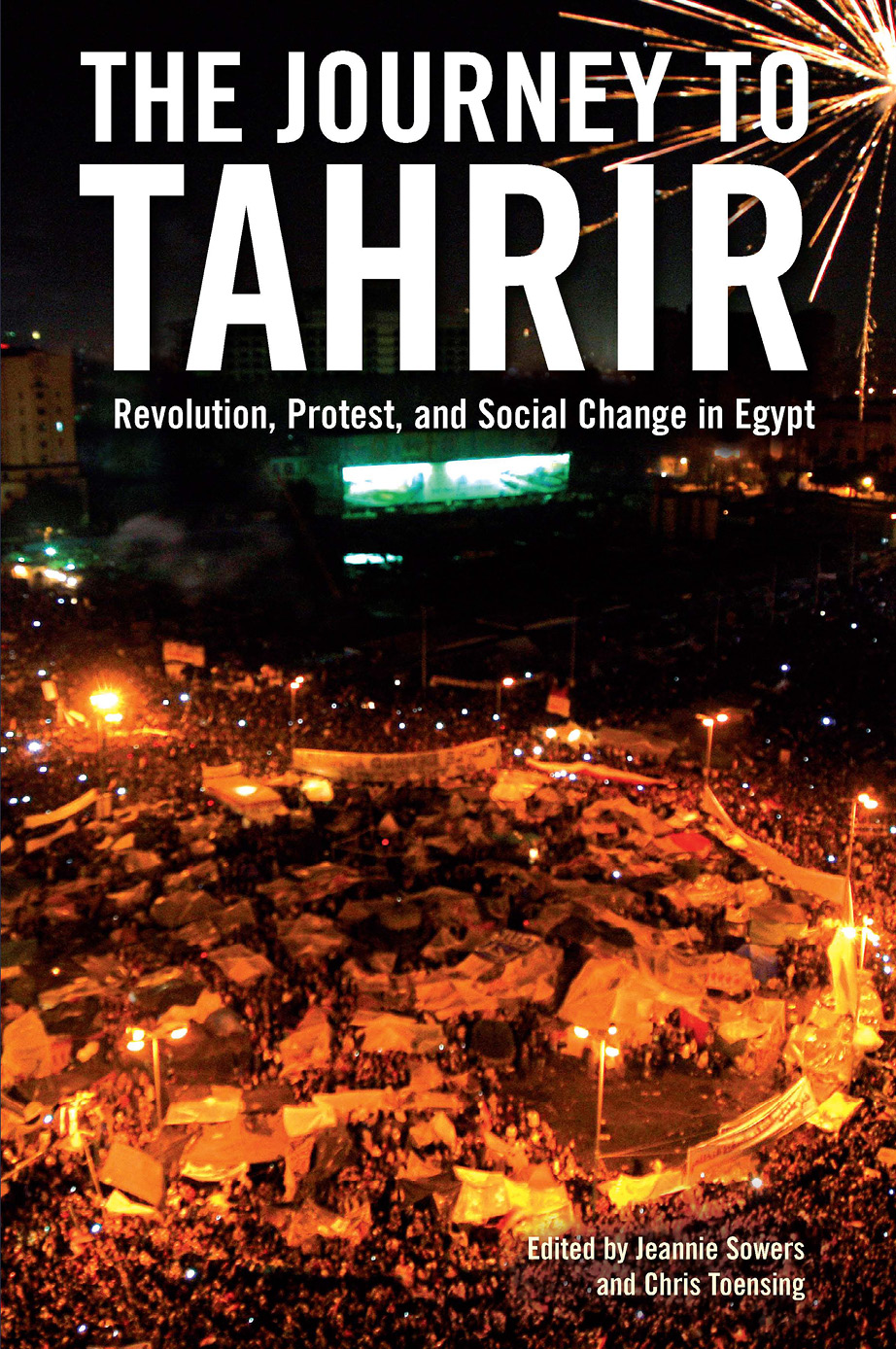

The Journey to Tahrir

REVOLUTION, PROTEST,

AND SOCIAL CHANGE IN EGYPT

Edited by Jeannie Sowers

and Chris Toensing

This edition first published by Verso 2012

The collection Verso 2012

The contributions the contributors 2012

Translation of Chapter 19 Ann Delehanty 2012

Chapter 4 first appeared in the online magazine Jadaliyya .

Chapter 9 is primarily based upon three articles published by MERIP: Popular Social Movements and the Future of Egyptian Politics, Middle East Report Online , March 10, 2005; Strikes in Egypt Spread from Center of Gravity (with Hossam el-Hamalawy), Middle East Report Online , May 9, 2007; and The Militancy of Mahalla al-Kubra, Middle East Report Online , September 29, 2007. It also draws upon material previously published in the Nation and Foreign Policy s Middle East Channel.

Chapter 12 draws from three articles published by MERIP: Egypts Paradoxical Elections, Middle East Report 238 (Spring 2006); The Dynamics of Egypts Elections, Middle East Report Online , September 19, 2010; The Liquidation of Egypts Illiberal Experiment, Middle East Report Online , December 29, 2010. The author would like to express her gratitude to Sayed El-Ghobashy, George Gavrilis, Mandy McClure, and Chris Toensing for very helpful criticism and advice on these articles.

Chapter 17 draws on joint publications by Marsha Pripstein Posusney (19512008) and Karen Pfeifer, and from published and unpublished manuscripts written separately by the two authors and collated by Pfeifer for this volume.

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

Epub ISBN-13: 978-1-84467-803-7

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The journey to Tahrir : revolution, protest, and social change in Egypt, 1999-2011 / edited by Jeannie Sowers and Chris Toensing.

p. cm.

This book is a collective effort by the contributing authors to Middle East Report.--Acknowledgements.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-84467-875-4

1. Egypt--Politics and government--21st century. 2. Egypt--Social conditions--21st century. 3. Protest movements--Egypt--History--21st century. I. Sowers, Jeannie Lynn, 1967- II. Toensing, Christopher J.

DT107.87.J68 2012

962.055--dc23

2012001432

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

For Egypts activists

Contents

Acknowledgements

This book is a collective effort by several contributing authors to Middle East Report , whose original essays provided such rich material for this collection. The authors graciously supported this project from the outset and provided timely revised submissions in the midst of the momentous political change sweeping across the Arab world.

The advice and prompt assistance of our commissioning editor at Verso, Sebastian Budgen, and the managing editor, Mark Martin, made working with Verso a pleasure. Michelle Woodward, the photo editor for Middle East Report , found the wonderful pictures that open each section of the volume. Sasa Tang helped format the typescript with care. Amanda Ufheil-Somers, assistant editor of Middle East Report , took on extra duties so that Chris Toensing might work on this project.

Jeannie Sowers thanks the College of Liberal Arts, University of New Hampshire, for supporting research in Egypt during the summer of 2011. She is also grateful to her husband Ben Chandran and son Evan for their support and humor during this project.

CHAPTER 1

Egypt in Transformation

Jeannie Sowers

At sunset on June 6, 2011, Egyptians once again demonstrated their creativity and tenacity in staging public protests. Activists stood motionless on Cairos Qasr al-Nil bridge, shoulder to shoulder, facing each other across four lanes of choked traffic, garbed in black. A few talked in quiet voices, others held signs, but most kept silent with folded hands as taxis, microbuses, and cars filled with passengers crawled past. Occasionally a young man came down the line, reminding participants they would soon move across the bridge, through the streets near Tahrir Square, and assemble in front of the Ministry of Interior, the government authority responsible for the detested internal security forces.

This silent stand-in was in memory of Khalid Said, a twenty-eight-year-old man beaten to death on an Alexandria sidewalk by security forces exactly one year before. The brazen brutality had galvanized citizens across the country, coordinated anonymously through the We Are All Khalid Said Facebook page and other social media, to take to the streets. On July 23, 2010, activists mounted the first in the series of stand-ins. To avoid the draconian restrictions on public gatherings enshrined in Egypts Emergency Law, organizers in Alexandria and Cairo asked participants to stand a few meters apart, facing the sea or the Nile if possible, in quiet contemplation or prayer. The novel form of protest attracted unexpectedly large crowds, prompting one commentator to wonder if the thunderous silence on the Nile in the summer of 2010 presaged greater civil unrest.

And indeed it did. In early 2011, after Tunisias long-standing dictator fled in the face of a mass uprising, millions of people turned out on the streets of Cairo and other Egyptian cities to demand that President Husni Mubarak step down. The Qasr al-Nil bridge, like other thoroughfares, became the site of some of the most visible clashes between state security forces and protesters during the January 25 revolution, as it is known in Egypt. Defying the black-clad conscripts of the regimes Central Security Forces, protesters tried to make their way across the bridge to converge on Tahrir Square. They encountered tear gas, bullets, water cannons mounted on armored vehicles, and phalanxes of state security. As captured on videos posted on the Internet and viewed around the world, however, the protesters regrouped, pushed forward behind improvised barricades, and sometimes broke through as the security forces retreated in disorder.

The battles on the Qasr al-Nil bridge were only some of many attacks on protesters across Egyptian cities, often at night, in places with far less media coverage. The courage and determination of many ordinary Egyptians to stay in the streets forced the military to remove Mubarak from office and assert direct control over the country after a mere eighteeen days. Those who participated in the uprising were not simply out to end Mubaraks thirty-year hold on power. Like their counterparts in Tunisia, protesters wanted to create a political regime that would respect dignity, rights, and justice, not trample upon them.

Embedding such principles in any political system, even consolidated democracies, is an ongoing challenge. But it is a particularly difficult task when the key institutions and personnel of the ancien rgime are entrusted with revolutionary goals. Egyptians were initially grateful that the military eased Mubarak out of power, preventing an escalation of the repression and atrocities that unfolded in Syria, Bahrain, Yemen, and Libya. By the summer of 2011, activists became frustrated by the military councils refusal to repeal the Emergency Law, restructure the security services, or make concrete preparations for elections. The military, a pillar of the Mubarak regime, continued to employ many of the techniques of control and repression that security forces had used in previous years. The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) criminalized protests and strikes through new laws issued by decree, arrested protesters and tried civilians in military courts, and detained individuals on vague and often questionable charges of subversion, espionage, and treason. Some pro-democracy activists bravely questioned these tactics in blogs, TV interviews, and the press, and were then invited in for questioning by the military council. At the same time, however, the public trials of former President Mubarak and his former interior minister went ahead as announced, an unthinkable event just six months earlier, while there is no indication that the SCAF has retreated from its commitment to hold substantive parliamentary and presidential elections.

Next page