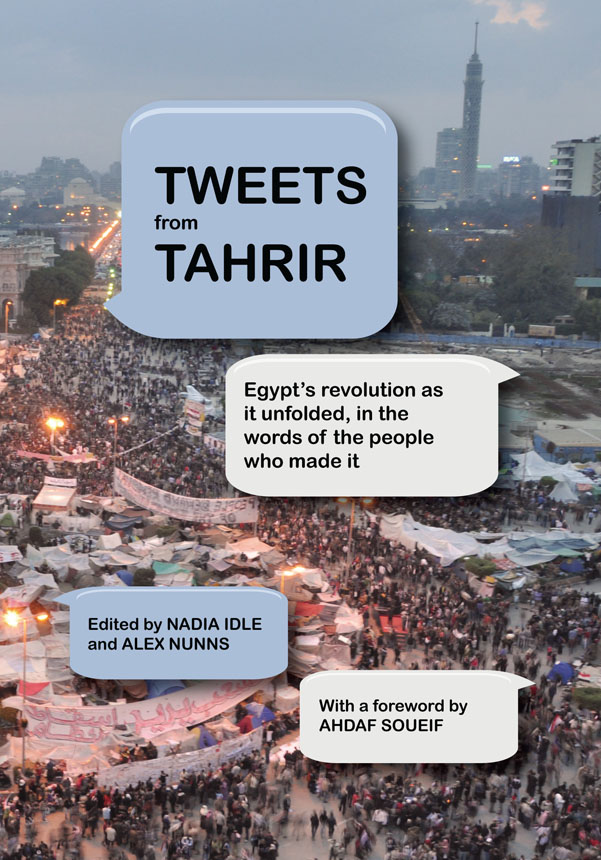

TWEETS from TAHRIR

TWEETS from TAHRIR

Egypts revolution as it unfolded, in the words of the people who made it

Edited by ALEX NUNNS and NADIA IDLE

OR BOOKS

New York

First published by OR Books, New York, 2011 www.orbooks.com

Copyright in this collection Nadia Idle and Alex Nunns Individual Tweets copyright the Tweeters

Foreword copyright Ahdaf Soueif: 2011

ISBN Paperback 978-1-935928-45-4 ISBN E-book 978-1-935928-46-1

Library Of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP Record is available for this book from the Library of Congress

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A CIP Record is available for this book from the British Library

Printed by BookMobile in the United States of America

Dedicated to the Egyptian revolutionaries

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

Ahdaf Soueif

I THINK WERE AGREED: Without the new media the Egyptian Revolution could not have happened in the way that it did. The causes were many, deep-rooted, and long-seated. The turning moment had come but it was the instant and widespread nature of the new media that made it possible to recognize the moment and to push it into such an effective manifestation.

What happened next has already become legend. Lines and images from the three weeks that followed January 25, 2011, have imprinted themselves not just on the Egyptian psyche but on the memory and imagination of the world.

I have friends on antidepressants who, over the twenty days of revolution, forgot to take their pills and have now thrown them away. Such is the effect of the Egyptian Revolution.

On Friday, February 11, the day Mubarak fell, Egypt partied. Chants and songs and drums and joy-cries rang out from Alexandria to Aswan. The defunct regime was only mentioned in reference to we want our money back.

Otherwise, three chants were dominant and very telling: One Lift your head up high; youre Egyptian was a response to how humiliated, how hopeless wed been made to feel over the last four decades.

The second was: Well get married. Well have kids, and reflected the hopes of the millions whose desperate need for jobs and homes had been driving them to risk their lives to illegally cross the sea to Europe or the desert to Libya.

The third chant was: Everyone who loves Egypt, come and rebuild Egypt.

And the next day, they were as good as their word: They came and cleaned up after their revolution. Volunteers who arrived on Tahrir Square after midday found it spick and span, and started cleaning up other streets instead. I saw kids perched on the great lions of Qasr el-Nil Bridge buffing them up.

I feel and every parent will know what I mean I feel that I need to keep my concentration trained on this baby, this newborn revolution I need to hold it safe in my mind and my heart every second until it grows and steadies a bit. Eighty million of us feel this way.

Eighty million at least because the support weve been getting from the world has been phenomenal. Theres been something different, something very special, about the quality of the attention the Egyptian revolution has attracted: its been personal.

People everywhere have taken whats been happening here personally. And theyve let us know. And those direct, positive, and emotional messages weve been receiving have put the wind in our sails.

We have a lot to learn very quickly. But were working. And the people, everywhere, are with us.

It remains to be seen whether the tools that helped achieve the impetus and immediate success of the Revolution will also help in the tasks that lie ahead: building consensus, building institutions, mending the damage, and molding the future.

PREFACE

AS AN EGYPTIAN WATCHING the live images of Tahrir Square on her computer at work in London, Nadia Idle, one of the editors of this book, could no longer take it. After much hesitation and several false starts, one irrepressible drive took over all other thoughts; she just had to be there. She booked a flight, told one friend, and sent an email to her boss a few hours before getting on a plane on the night of

February 7, 2011.

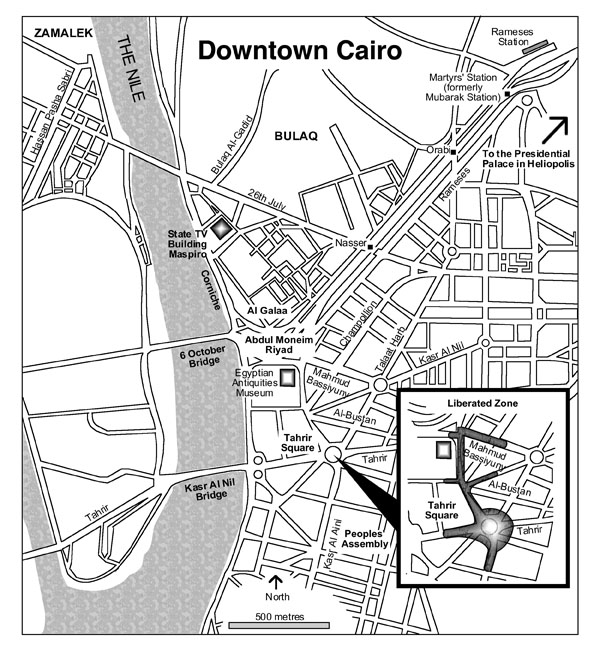

All the things that had worn her down to the point of leaving Egypt the unrelenting harassment of women, the lack of civic pride, a people whose broken soul seemed to permeate any human interaction, day in and out seemed to have evaporated. Tahrir was a space of unity, pride, resistance, celebration, laughter, sharing, and most importantly ownership. This was the Peoples space; our rules and our demands. We would not leave until justice was born.

Meanwhile, back in England, Alex Nunns, the other editor of this book, was transfixed by events. The twenty-four-hour news channels had cameras stationed on top of buildings overlooking Tahrir, so the revolution really was televised. But he found that the most compelling coverage was on Twitter, coming directly from the people in the square. The tweets were instant, and so emotional and exciting that anyone following them felt an intense personal connection to what was happening in Tahrir.

This book is an immediate attempt to document a fraction of those remarkable messages before they disappear into the vacuum of cyber-space, and to allow the story of this historic uprising to be told by the people who made it happen.

The tweets are valuable for two reasons: as firsthand, real-time accounts of events (a primary source for historians of the Egyptian Revolution); and as testimony to the significant role that Twitter and other social media played in those events.

It is important to say up front that we do not claim that this collection is comprehensive. It is merely a sample of some of the activity that was taking place on Twitter. To print every tweet that related to the uprising would take several volumes. One activist alone managed to tweet 60,000 words during the revolution! Neither do we claim to have included all of the key tweeters who took part. We are bound to have overlooked some and underrepresented others.

Rather, we have sought to present a readable, fast-paced account of the Revolution that gives a sense of what was being said on Twitter. At the core of our approach are several key people whose tweets run right through the work. We hope the reader will get to know them (because remarkably their personalities do come across in messages of 140 characters) and follow their different journeys as the Revolution unfolds. Aside from this core group, many other tweeters make less frequent appearances. Our intention was to begin the account with just a few voices, and broaden it out as the days passed, reflecting the progression of the demonstrations themselves as more and more people joined.

We have concentrated on tweeters in Cairo. The Revolution happened across Egypt, with particularly strong movements in Suez and Alexandria. Whole books could and should be written about these struggles, but the epicenter of events was in the capital. We also chose not to include tweets from important players who were outside Egypt. For example Mona Eltahawy, an Egyptian writer living in New York, was very active promoting the cause on Twitter and relaying information back to those in Egypt, but she was not reporting from the ground.