Table of Contents

Also by Lloyd C. Gardner

Three Kings: The Rise of an Empire in the Middle East after World War II

The Long Road to Baghdad:

A History of U.S. Foreign Policy from the 1970s to the Present

Economic Aspects of New Deal Diplomacy

Architects of Illusion:

Men and Ideas in American Foreign Affairs, 19411949

The Creation of the American Empire: U.S. Diplomatic History

(with Walter LaFeber and Thomas McCormick)

American Foreign Policy, Present to Past

Looking Backward: A Reintroduction to American History

(with William ONeill)

Imperial America: American Foreign Policy, 18981976

A Covenant with Power: America and World Order from Wilson to Reagan

Safe for Democracy:

The Anglo-American Response to Revolution, 19131923

Approaching Vietnam: From World War II to Dienbienphu

Spheres of Influence:

The Great Powers Partition in Europe, from Munich to Yalta

Pay Any Price: Lyndon Johnson and the Wars for Vietnam

The Case That Never Dies: The Lindbergh Kidnapping

Edited by Lloyd C. Gardner

The Great Nixon Turnaround:

Americas New Foreign Policy in the Post-liberal Era

America in Vietnam: A Documentary History (with Walter LaFeber,

Thomas McCormick, and William Appleman Williams)

Redefining the Past: Essays in Honor of William Appleman Williams

On the Edge: The Early Decisions in the Vietnam War (with Ted Gittinger)

International Perspectives on Vietnam (with Ted Gittinger)

Vietnam: The Search for Peace (with Ted Gittinger)

The New American Empire:

A 21st Century Teach-In on U.S. Foreign Policy (with Marilyn B. Young)

Iraq and the Lessons of Vietnam:

Or, How Not to Learn from the Past (with Marilyn B. Young)

To the memory of four great teachers: Doris Evans, Dorothy Whitted, Ben Spencer, and Dave Jennings. In the past we are found.

INTRODUCTION

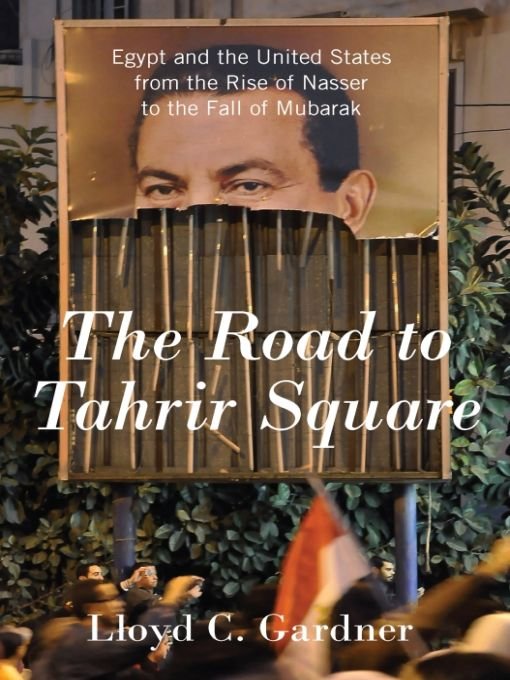

Clinton, in Cairos Tahrir Square, Embraces a Revolt She Once Discouraged

Headline on a story by Steven Lee Myers, New York Times, March 16, 2011

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton was the first high-level Obama administration figure to go to Cairo after the popular uprising that toppled Hosni Mubarak, Washingtons most reliable ally in the Middle East for over a generation. To see where this revolution happened, she exulted on a walk through Tahrir Square, and all that it has meant to the world, is extraordinary for me. The New York Times headlined her stroll, however, as something more like catch-up with a racing series of events that had left the United States unsure of where it stood now that a pillar of its Middle East policy had disappeared.

The initial wavering in the Obama administration when the protests began on January 25, 2011, reflected uncertainty and fear about the future. Secretary Clinton said on that first day of protests, Our assessment is that the Egyptian government is stable and is looking for ways to respond to the legitimate needs and interests of the Egyptian people. One implication of that statement was that the United States felt able to judge what was legitimate and what was not. The president then spoke with Mubarak on the telephone, urging him not to resort to force, while Vice President Joe Biden, in an effort to encourage a peaceful solution, refused initially on American television to call the Egyptian president a dictator. Many more telephone calls over the next two weeks were made by Secretary of Defense Robert Gates and the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral Mike Mullen, to their Cairo counterparts, at first in an attempt to learn what the Egyptian armed forces believed about the protestors, and then, when it became clear that Mubarak would not step down, to prevent the military from taking sides.

While the Pentagons main concern was not to lose touch with an army in which it had invested over $50 billion since the time Mubarak had come to power, two of Americas other allies, Israel and Saudi Arabia, fretted about U.S. policy in abandoning the aging dictator who had controlled Egyptian politics with unquestioning support from the military. Americans had paid little attention, on the other hand, to the policies their government had followed during the Mubarak era, let alone to the background story of how Washington had finally developed such a close relationship after a series of missteps in the years since the 1952 Egyptian Revolution. Now more than ever, with the revolutionary spirit inspiring protestors in country after country, the debate over future policies required a historical grounding. This book opens a door on that past.

At first there had been Gamal Abdel Nasser, whose determination to lead the Arab world away from reliance on the United States and the West at the height of the Cold War forced an unhappy Eisenhower administration to make difficult choices opposed to its European allies during the 1956 Suez Crisis. Then there had been Anwar el-Sadats audacious initiatives beginning with the October War in 1973 that surprised Nixon and Kissinger as well as Jimmy Carter. Finally, after Sadats assassination, Hosni Mubarak had emerged, a man whose enormous ambition to rule matched perfectly Washingtons desire to make Egypt into what it had always wanted it to be: a loyal ally who held the line against radical nationalism in the Arab world.

Mubarak had kept Sadats peace with Israel (negotiated over the heads of other Arab countries) and provided public support for Americas policies elsewhere in the Middle East (especially Iran and Iraq). And, notably, Mubarak provided pivotal support to the George W. Bush administrations War on Terror, cooperating with the CIAs rendition program by accepting suspects sent to Egypt for questioning using methods that could not be approved elsewhere after they became known, including waterboarding and other forceful interrogation techniques.

Of course, Mubarak expected to be paid, and paid handsomely. In exchange for these services, the United States provided Egypt with military aid totaling nearly $1.5 billion a yearsecond only to Israels subsidyand hoped for the best as far as Mubaraks internal policies. Generally speaking, such hopes took the same form as the Clinton administrations attitude toward gays in the U.S. military: dont ask, dont tell.

After the attacks of September 11, 2001, when the supposed weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) that Iraqs Saddam Hussein had hidden away could not be discovered and indeed were found not to exist, the Bush administration turned to the rhetoric of spreading democracy as the motive for war against Saddams regime. Wilsonian idealism of this sort is often invoked to cover embarrassing gaps (like the missing WMDs) and to couch the protection of such material interests as oil wells on a higher plane of motivation. But it is a risky ploy, for ideas can take on their own momentum.

The events at Tahrir Square would likely have occurred without American rhetoric after 9/11, of course. Yet whether they would have occurred without years of unstinting American support to Mubarak is a far more interesting question. Would Mubarak have felt able to pursue his repressive policies had he not enjoyed full American backing across nearly three decades?