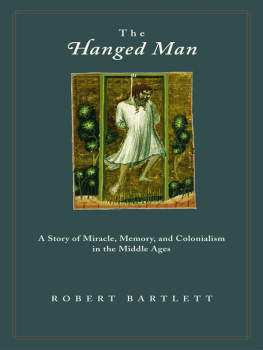

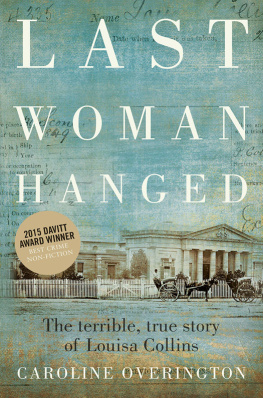

The

HANGED MAN

Copyright 2004 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

3 Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY

All Rights Reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bartlett, Robert, 1950

The hanged man : a story of miracle, memory, and colonialism in the Middle Ages / Robert Bartlett.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-691-11719-5 (acid-free paper)

1. HangingWalesHistoryTo 1500Case studies. 2. Executions and executionersWalesHistoryTo 1500Case studies. 3. Near-death experiencesReligious aspectsChristianityHistory of doctrinesMiddle Ages, 6001500. 4. ResurrectionHistory of doctrinesMiddle Ages, 6001500. 5. MiraclesHistory of doctrinesMiddle Ages, 6001500. 6. Examination of witnessesWalesHistoryTo 1500. 7. HangingWalesHistoryTo 1500. 8. WalesHistory12841536. I. Title.

HV8579.B37 2004

942.036dc21 2003045783

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

This book has been composed in Adobe Caslon Printed on acid-free paper.

www.pupress.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

In Memoriam

R. W. Southern (19122001)

Preface

T his book takes as its starting point a dramatic eventthe hanging and miraculous resurrection of a Welshman seven hundred years ago. Although the episode took place in such a distant period, we have unusually rich information about it, for no fewer than nine eyewitness accounts survive, each of them long, detailed, and vivid. The interlocking narratives of these witnesses are worth recounting for their own intrinsic interest, although it is important to understand the circumstances in which they came to be recorded, because the witnesses were giving evidence before a judicial commission and what they said was very much guided by the questions they were asked. The commission that heard the evidence about the hanging and its aftermath was concerned not with the rights and wrongs of the case but with the circumstances of the hanged mans revival: had it been the result of a miracle? This commission was a canonization inquiry, established by the pope to ascertain whether a bishop of Hereford of an earlier generation was or was not a saint. If the dead bishop had acted as a heavenly intercessor for the hanged man, this would support the claim that he was a saint; if not, not. By this point in the Middle Ages there were complex and detailed rules governing canonization, and these transactions cast much light on what people of the time considered supernatural and how they thought the supernatural could be identified.

Yet, although the issue of miracle and sanctity was the central concern of the inquiry, every part of the proceedings gave rise to new issues and new questions, which sprout strands like a tropical vine. We can try to delve deeper into what the witnesses said and what it meant. This can lead to very personal and individual questions, such as how people in the Middle Ages conceived of space and time and how their memories worked. On the other hand, using the record as a focal point, we can pan back to set it in context in the wider world of the time. This takes us to the great public events of the periodthe English conquest of Wales; the trial of the Templars; or the troubles of the reign of Edward II, the first king of England to be deposed and murdered. Especially prominent is the complex world of colonial Wales, with its semi-independent Marcher lords and its long tradition of native resistance and rebellion. There is also more evidence here for the details of execution than we might wish to have.

The story involves a diverse group of people. They came from many levels of medieval societylords and ladies, laborers, bishops and priests, rebelsand from a wide geographical range: clergymen from Gascony in southern France interrogate an English lord in London, while in Hereford a group from southern Wales is also questioned, raising some difficult translation problems for a French bishop facing the unfamiliar sound of the Welsh language. About some of this cast of characters it is possible to know a fair amount and even to infer details of their personalities and their relations with each other. For example, there seems to have been little sympathy between the highborn lady who interceded unsuccessfully for the condemned man and her stepson, who describes the corpse after the hanging in a manner that suggests gleeful satisfaction. Especially in the case of the wealthier and more powerful participants in this story, we can trace their careers both before and after their involvement in the proceedings; some of them were important figures in Church and State, diplomats, careerists, barons, and cardinals.

The story told in this book is both less and more than a reconstruction of events. It is less because it acknowledges that it is now impossible to create a complete and accurate narrative of what happened when the Welshman was hanged and revivedimpossible because of gaps in our knowledge and discrepancies in the testimony. Yet it is also more than a reconstruction, for it recognizes that those gaps and discrepancies actually provide an opportunity, by showing us revealing and unusual circumstances or raising fruitful problems that cast light both on central issues and on the byways of the medieval period. The extraordinary episode of the hanging and revival of the Welshman offers a window on the wider medieval world. By analyzing the record carefully, as if with a magnifying glass, we can see details of life and thought in the Middle Ages that would otherwise not be known to us. Reading the statements that the witnesses made gives us as good an idea as we are likely to get of the spoken words of the past in the time before the tape recorder.

The

HANGED MAN

The Story

I n the summer of 1307 an inquiry opened in London to investigate whether Thomas de Cantilupe, bishop of Hereford, who had died twenty-five years earlier, could rightly be regarded as a saint. Three commissioners, entrusted with the task by Pope Clement V, had been empowered to hear testimony about the bishops life, the general reputation he enjoyed, andsomething crucial for a favorable outcome to a canonization processthe miracles he had performed after death.

Among the first witnesses to be heard were the aristocratic lady Mary de Briouze, her stepson William de Briouze, and a chaplain of the de Briouze family, all giving evidence about the same miracle. This concerned a Welshman, William Cragh, who had been hanged for homicide on the orders of William de Briouze senior, the deceased husband of Mary de Briouze and father of William junior. It was claimed that he had been miraculously resuscitated through the intercession of Thomas de Cantilupe. This event had taken place, according to Lady Mary de Briouze, about fifteen years earlier, though she was uncertain of the exact day and month, but believed it was in winter. Her stepson was more precise: William Cragh had been captured between Michaelmas and All Saints Day next, eighteen years ago. The chaplain offered a third dating: The events about which he had given evidence took place sixteen years ago. Such minor vagaries of memory are not unusual; in the medieval period they would have been far more common than today, when we experience the constant hammering home of past dates by documents such as birth certificates and passports and the reiteration of current dates in newspapers and news broadcasts.

Next page