HarperCollinsPublishers

First published in Australia in 2014

by HarperCollinsPublishers Australia Pty Limited

ABN 36 009 913 517

harpercollins.com.au

Copyright Caroline Overington 2014.

The right of Caroline Overington to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright Amendment (Moral Rights) Act 2000.

This work is copyright. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers

Level 13, 201 Elizabeth Street, Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia

Unit D1, 63 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand

A 53, Sector 57, Noida, UP, India

1 London Bridge Street, London SE1 9GF, United Kingdom

2 Bloor Street East - 20th Floor, Toronto, Ontario M4W 1A8, Canada

195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007, USA

978 0 7322 9972 9 (hbk.)

978 1 4607 0362 5 (ebook)

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication data:

Overington, Caroline.

Last woman hanged / Caroline Overington.

EPub Edition October 2014 ISBN 9781460703625

Notes: Includes bibliographical references.

Collins, Louisa, 18481889.

Women murderers New South Wales.

True crime stories.

364.15230944

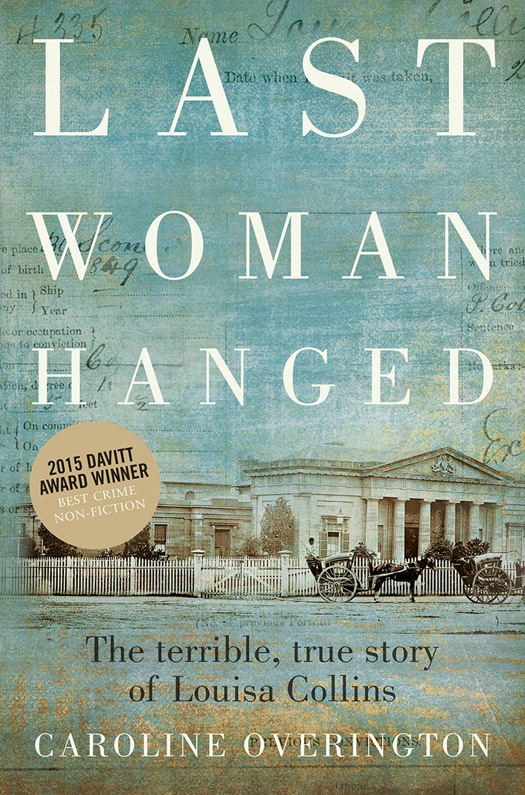

Cover design by Darren Holt, HarperCollins Design Studio

Cover images: Darlinghurst Gaol and Court House, Sydney, 1870 by Charles Pickering/State Library of NSW (SPF/253, a089253); background textures by shutterstock.com

This book is dedicated to the memory of those women who fought so hard to save Louisa, and for so many of the rights that women enjoy today.

CONTENTS

Guide

O n 8 January 1889, Louisa Collins, a 41-year-old mother of ten children, became the first woman hanged at the Darlinghurst Gaol and the last woman hanged in New South Wales.

Dark-eyed, dark-haired, plump-of-figure, beautiful all these words had been used to describe Louisa. Also: drunk. Louisa liked to drink brandy and she liked to drink beer and when she got drunk she liked to dance by the light of the lamp, even as her many children crawled on the dirty floor around her feet.

Louisa had twice been married, and unlucky for some she had twice been widowed. Over six tense months in 1888, the centenary year in New South Wales, she was tried not once, but four times for the murder of one or the other of her husbands.

Some of the strongest evidence against Louisa came from her only daughter, tiny fair-haired May, who was just ten years old when first asked by a judge of the Supreme Court to take the stand with a Bible in her hand and testify against her mother.

The execution of Louisa Collins was ghastly, not only because executions generally are, or because Louisa was a woman, but because the hangman in New South Wales at that time, the gruesome Nosey Bob, was inept. He misjudged the length of the drop, and nearly tore Louisas head off. So terrible was the scene Louisa was left to dangle for twenty minutes, with blood dripping from a gaping wound in her throat that no woman would ever again be hanged in New South Wales.

The first question this book seeks to answer is perhaps the most obvious one: did she do it? Was Louisa guilty? This requires a rigorous examination of the original evidence, including trial notes and forensic reports, most of which are stored at State Records New South Wales.

The aim throughout has been to ensure that everything recorded here as opposed to anything that might have been said about Louisa at the time is true: therefore, if a character says or does something on these pages, it is because they were recorded as saying or doing so, at the time of Louisas trials.

That said, all evidence must be read in its historical context: Louisa Collins died at a time when women were in no sense equal under the law, except when it came to the gallows. Women could not vote. They could not sit in parliament. There were no female judges and no female jurors either.

The space available for women to have their say to express an opinion about capital punishment, for example was limited. The space available to them to exercise real power, in a legal and political sense, was non-existent. Also important is the fact that Louisa was a poor woman, in debt even to the undertaker. The Crown, by contrast, was equipped with the best of the colonys barristers, for all four trials.

A story like this one, where both the stakes and the body count are high, inevitably features heroes and villains. To some extent, it will be for the reader to decide the category into which Louisa should fall. What is certain is that two of the colonys most powerful men the premier, Sir Henry Parkes, and His Excellency, the governor, Lord Carrington ultimately declined to intervene on Louisas behalf. In their absence, it fell to the little people many of them women to find the moral courage to try to save her life. Their argument was both passionate and compelling, and may today seem obvious: that a legal system comprised only of men male judges, all-male jury, male prosecutor, governor and premier could not with any integrity hang a woman.

The tenacity of these women would not, in the end, save Louisa Collins, but it would ultimately carry women from their homes in the new colony of New South Wales all the way to Parliament House. Little more than a decade after Louisa was hanged, Australian women would become some of the first in the world to get the vote. They would take seats in state parliaments, and in Canberra. They would become doctors, lawyers, judges, premiers even the prime minister.

Besides being the true story of one womans life, this book should be read as a letter of profound thanks to that generation of Australian suffragettes who fought so hard for so many of the rights that women enjoy today. Their first steps into the political arena may have been tentative, but a wave rose in their wake and it would prove unstoppable. The delight and surprise in researching their lives was in discovering that some of their descendants as well as some of Louisas still walk among us. Surely their spirit does, too.

Caroline Overington

Sydney, 2014

A ccording to various sources, Louisa Collins was just thirty-two years old when she was hanged at the Darlinghurst Gaol in 1889 or else she was thirty-nine or perhaps forty. Not even prison officials could seem to make up their minds.

In fact, if the official records are correct, Louisa must have been forty-one years old when she died. Both her birth certificate and her certificate of baptism make plain that she was born Louisa Hall on 11 August 1847 at Belltrees, near Scone, and no amount of lying about her age, which Louisa had a habit of doing, could make a difference to that date.

Typically enough for the time, Louisas father, Henry Hall, was a convict. The particulars document attached to his file describes him as having a scar over his eye and a pock-marked, ruddy complexion. He was also short and a thief. the couple went to live and labour at Belltrees.