Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

A Note on Language

A prolific journal and letter writer, Louisa May Alcott was at times cavalier about spelling, grammar, and punctuationand fond of lively slang or made-up words, like perwerse. For flavor and authenticity, the author has retained Alcotts original text and formatting.

Copyright 2020 by Deborah Noyes

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Schwartz & Wade Books, an imprint of Random House Childrens Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Schwartz & Wade Books and the colophon are trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Visit us on the Web! rhcbooks.com

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at RHTeachersLibrarians.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Noyes, Deborah, author.

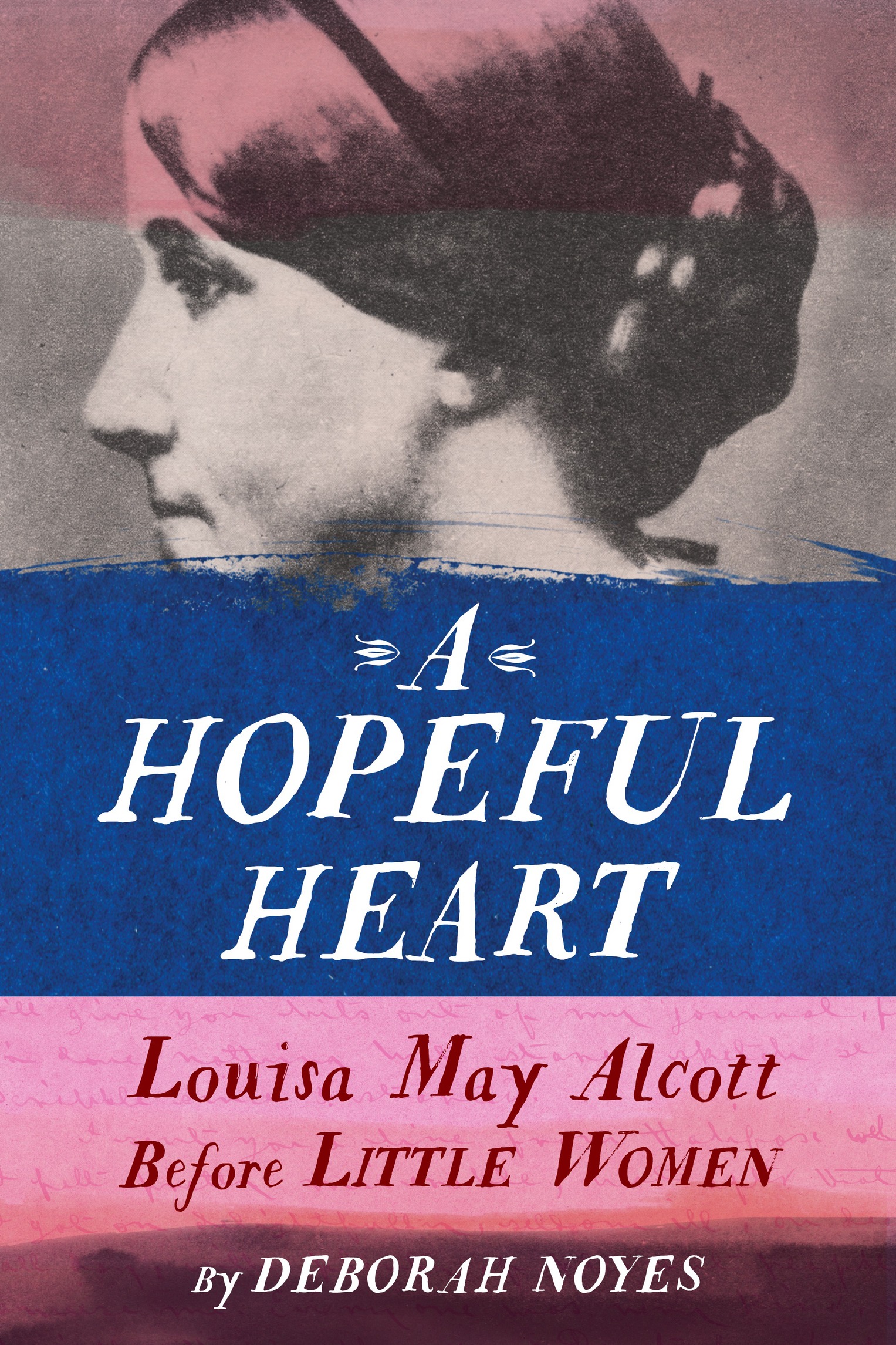

Title: A hopeful heart: Louisa May Alcott before Little Women / Deborah Noyes.

Description: First edition. | New York: Schwartz & Wade Books, [2020] |

Includes bibliographical references and index. | Audience: Ages 812. | Audience: Grades 79. | Summary: A middle-grade biography about literary icon Louisa May Alcott

Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020014513 | ISBN 978-0-525-64623-5 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-0-525-64624-2 (library binding) | ISBN 978-0-525-64625-9 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Alcott, Louisa May, 18321888Juvenile literature. | Women authors, American19th centuryBiographyJuvenile literature.

Classification: LCC PS1018 .N69 2020 | DDC 813/.4dc23

Ebook ISBN9780525646259

Random House Childrens Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

Penguin Random House LLC supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin Random House to publish books for every reader.

ep_prh_5.6.0_c0_r0

For Lisa

Contents

From her father she received pride, intellect, and will; from her mother passion, imagination, and the fateful melancholy of a woman defrauded of her dearest hope.These two masters ruled soul and body, warring against each other.

Louisa May Alcott, Moods

She has withstood the temptations of the appetites through a whole morning, and though they triumphed, at last, the triumph was not without a struggle.

Amos Bronson Alcott, journal, 1833

Louisa May Alcott never liked her birthday. On a dismal November day I found myself, as she put it, and began my long fight.

Her mother remembered that day in 1832and her daughterdifferently. The infant Louisa was a sprightly, merry little puss, Abigail Alcott wrote, quirking up her mouth and cooing at every sound.

Louisa the fighter found herself in the heart of an unusual family.

Amos Bronson Alcott, Louisas father, was an educator and philosopher fascinated by human nature. Louisas mother shared his ideals and was fiercely committed to social change.

When Anna, the first of four Alcott daughters, was born on March 16, 1831twenty months before LouisaBronson wrote grandly, A child is given. May we guide it in the paths of truth. He saw the new baby as an invitation to a great experiment: What is human happiness? Can it be built from the ground up? Can parents limit outside influences and raise a perfect child? How do children learn?

To find out, he took scrupulous notes on his firstborns mental and moral growth. He looked and listened, like any attentive father, but also exposed Anna to stimuli, like a scientist. What faces would she make? What sounds and gestures? His laboratory was built on gentleness and reason, but Bronsons curiosity sometimes got the better of him. What would happen, for instance, if he made a scary face? (That experiment must not be repeated, he concluded. Fear, however mild, only subtracted from a childs happiness.)

He called his journal Observations of the Life of my First Child and intended it to be no less than a history of the human mindfaithfully narrated.

Louisa arrived in the world on Bronsons thirty-third birthday, and she too became part of the family experiment.

The sisters were in every way a study in contrasts, their father observed.

Bronson believed in the divine purity of young children: newborns came into the world still in touch with instincts and intuition from the spiritual realm. Mild, sentimental, and eager to please, Anna was fair and serene like her father. She fit his concept of the ideal infant.

Louisa, with her vivid, energetic power, individuality, and force, did not. An active, fretful baby, she challenged her fathers theories from the beginning (and would challenge him all her life).

Louisa was practical and proud, with a fierce will, imagination, and temper. She had storm-dark eyessome said gray, others blackand her mothers olive skin.

In a letter to his own mother, Bronson praised his wifes maternal devotion. She lives and moves and breathes for her family, he wrote. But at the same time, he gave Abby full credit, or blame, for the baffling phenomenon that was Louisa.

Overworked and in poor health during the formative early months of her daughters life, even Abby looked back and blamed herself for Louisas moodiness.

Born with the wild exuberance of a powerful nature, Louisa was certainly fit for the scuffle of things, as Bronson put it, and their household was nothing if not a scuffle.

Clamoring for the attention of two intellectual, socially active parents, toddler Anna lashed out at her mother and sometimes struck her. Anna slapped and scratched Louisa the intruder one minutethough she always agonized afterwardand slathered Louisa in kisses the next.

Not to be outdone, tiny Louisa mastered the art of the tantrum, learning to howl and collapse into a heap on the floor, wedging her head between her knees and screaming bloody murder. Sobbing before bedtime became one of her most confirmed habits.

Trying to mold the perfect family in crowded chaotic conditions wore on Bronson. The family lived at the time in Germantown, Pennsylvaniaabout six miles outside Philadelphiawhile he tested his radical educational methods at a suburban school funded by wealthy Quakers. His roles as father and educator were hard to separate, and with his suburban experiment on the wane and bills piling up, Bronson closed the Germantown school. He rented an apartment in the city of Philadelphia, leaving Abby to manage the girls and the household alone. Bronson disappeared into the hallowed halls of Philadelphias public library collections to study educational tracts and philosophy, and walked six miles each way on weekends to spend time in Germantown with the family.

On April 22, 1833, he opened a new school in the city with fifteen students, and while Abby and the girls occupied a series of boardinghouses in Germantown and then Philadelphia, Bronson kept his distance.

![Alcott - Louisa May Alcott: [a personal biography]](/uploads/posts/book/163779/thumbs/alcott-louisa-may-alcott-a-personal-biography.jpg)