Published with assistance from the Annie Burr Lewis Fund and the Mary Cady Tew Memorial Fund.

Copyright 2014 by The Estate of Margery Heffron.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Electra type by IDS Infotech Ltd., Chandigarh, India.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Heffron, Margery M., 19392011.

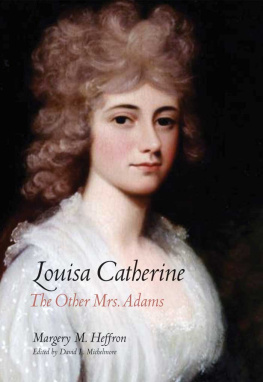

Louisa Catherine : the other Mrs. Adams / Margery M. Heffron ; edited by David L. Michelmore.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-300-19796-9 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Adams, Louisa Catherine, 17751852. 2. Presidents spousesUnited StatesBiography. 3. Adams, John Quincy, 17671848. I. Michelmore, David L., 1947 editor. II. Title.

E377.2.H44 2014

973.5'5092dc23 [B] 2013042868

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

C ONTENTS

A CKNOWLEDGMENTS

In October 2009, my sister Margery M. Heffron was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Two years and many hours of painful treatment later, in December 2011, she died, not knowing if the book into which she had poured every last bit of her heart and energy would ever be published. Carrying Louisa Catherine: The Other Mrs. Adams to the finish line took the combined efforts of a small army of friends, family, and fellow writers drawn to Margery's cause by her courage and endless enthusiasm. I give them my warmest thanks, hoping that those whose names I unwittingly omit will accept my apologies.

The book ends with John Quincy's inauguration as the nation's sixth president in March 1825, far short of where Margery had hoped to take it. She simply ran out of time. The chronology at the end of the book provides a brief outline of the remaining twenty-seven years of Louisa's life.

Margery wrote her first book at the age of eight, an elaborate Louisa May Alcott imitation called The Happy Family, and from then on had always wanted to be an author. On a visit to the Old House in Quincy, she found her subject in Louisa Catherine Adams, but, between family and career, it was another thirty years before she found the freedom to begin writing. Even then, she kept her ambitions largely to herself. That secrecy ended one evening at a Massachusetts Historical Society lecture in Boston when she happened to sit next to C. James Taylor, editor-in-chief of the Adams Papers. His immediate enthusiasm for her idea gave her a huge boost. It led to a long and fruitful relationship with the MHS and, eventually, to a Marc Friedlaender research fellowship. Judith Graham, Beth Luey, and Margaret A. Hogan, editors of the MHS's recently published two-volume Diary and Autobiographical Writings of Louisa Catherine Adams, gave her unwavering support and encouragement. It's impossible to thank them adequately. At the MHS, she also came in contact with Catherine Allgor of the University of California, Riverside, a well-known scholar, writer, and Louisa fan whose energetic support for the project did much to buoy Margery's spirits and to allay her fears that her work was, somehow, not scholarly enough.

As she began writing, Margery leaned heavily on colleagues in the Boston Biographers Group, a small, spirited organization that she had co-founded as a kind of support group for professional writers. Members of the groupparticularly Elizabeth Harris, Bernice Lerner, Melissa Nathanson, and Quincy Whitney, all of whom were working on biographies of their owncarefully read and commented on her work, chapter by chapter, just as she read and commented on theirs.

When Margery was too ill to do as much research as she needed to do, she enlisted her sister Mary Ackerman Hayes, a freshly retired school teacher, and me, a freshly retired newspaperman, to help. Mary worked tirelessly collecting and reading the Adams Papers on microfilm and providing Margery with notes and summaries and the kind of love that only a sister can provide. Mary received welcome help from Linda Madden, Interlibrary Loan Supervisor at the Mason Library of Keene State College, and Shane Harper, Resource Sharing assistant, at the Dartmouth College Library.

Elizabeth O'Connor McGurk, a college classmate of Margery's living in England, traveled to Ealing outside London to provide information for Chapter 12. Another college friend, Oriel Eaton, read every chapter as it was produced, acting as not only a proofreader/copy editor but also a general editor in addressing style and tone. And yet a third college friend, Livia Bardin, and her husband, David, a dogged researcher, dug through archival records in Washington, D.C., for new information on Louisa's family in Chapters 13 and 14. They received valuable assistance from Danny Brown at the Washington, D.C., Archives; Robert Ellis at the National Archives; and Hayden Bryan at St. John's Episcopal Church, Lafayette Square, in Washington.

Carlene Barous, a cousin, copyedited the first few chapters as Margery started treatment for her cancer. Karen Hammond, a writer and longtime friend of Margery's, copyedited the entire book before we sent it out to publishers. I would also like to thank Margery's oncologist, Dr. Elizabeth Buchbinder of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, for her care and support. I believe that Margery's determination to finish this book kept her alive much longer than could have been expected.

Margery's childrenAnne Sigler and John and Samuel Heffronand her grandchildrenKeats Iwanaga and William and Phineas Heffronshould be thanked for their patience, support, and love.

Margery's husband Frank encouraged her to follow her dream in writing this book. He read and offered patient, lawyerly advice on much of it; he accompanied her on research trips to London, Nantes, St. Petersburg, and Annapolis (where she suffered a frightening and serious fall that sidelined her for months).And, in Margery's last two years, Frank stayed beside her through scores of hospital visits, physician consultations, treatments, and bad news. For all that and more he deserves all our thanks.

David L. Michelmore

I NTRODUCTION

Then it was that the little Henry, her grandson, first remembered her, from 1843 to 1848, sitting in her panelled room, at breakfast, with her heavy silver teapot and sugar-bowl and cream-jug. By that time she was seventy years old or more, and thoroughly weary of being beaten about a stormy world. To the boy she seemed singularly peaceful, a vision of silver gray, presiding over her old President and her Queen Anne mahogany; an exotic, like her Svres china; an object of deference to every one, and of great affection to her son Charles; but hardly more Bostonian than she had been fifty years before, on her wedding-day, in the shadow of the Tower of London.

Next page